Clear, concise and unbiased information on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is difficult to find.

A-Mark Foundation has partnered with Dov Waxman, professor of Israel Studies at UCLA, to excerpt questions and answers from his 2019 book, The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: What Everyone Needs to Know, published by Oxford University Press.

Still have questions? Send us an email.

1. What are the Israelis and Palestinians fighting about?

A Palestinian protester yells at an Israeli soldier as he confronts him atop an Israeli army vehicle during a protest against Israeli forces conducting an exercise in a residential area near the Palestinian village of Naqura, northwest of Nablus in the occupied West Bank, on September 4, 2019. Photo Credit: Jaafar Ashtiyeh / AFP via Getty Images.

The conflict started around a century ago as an intercommunal conflict between Arabs and Zionist Jews living in the territory then known as Palestine. Fundamentally, it was a conflict between two communities whose dominant nationalist movements both claimed the right to exercise national self-determination and assume sovereignty over the same piece of land. After the Zionists succeeded in establishing their state in 1948, what was initially a conflict between two groups competing for statehood developed into a conflict between the State of Israel and Palestinians, who remained stateless.

Both sides insist that this land belongs to them, and both claim the right to exercise sovereignty over it. Palestinians believe that the land is rightfully theirs because they have inhabited it for centuries, and because they constituted a large majority of the local population until Israel’s establishment in 1948. Israeli Jews, on the other hand, claim that their ancestors lived there first and once ruled parts of it until they were forcibly driven into exile, during which they longed to return to their original homeland.

Photo Credits: Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division and United States Central Intelligence Agency, 1988.

Since both sides are convinced that exercising sovereignty over territory is essential to their future survival, Israelis and Palestinians believe that they are engaged in an existential conflict as well as a territorial conflict. It is also perceived to be an existential conflict because both sides suspect that the other is intent on destroying them.

During the course of the conflict, both sides have rejected not only the other’s territorial claims but also their very existence as a nation. Each has dismissed the other’s nationhood as false and invented and denounced the other’s national narrative as myths and lies. As a result of this mutual denial, the conflict has become a contest over national identities and the competing historical narratives that shape and sustain them. It is about the past as much as the present and the future. It is important to recognize these abstract, intangible elements of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in order to understand its intensity and intractability.

2. Who are the Israelis?

Israel’s population is a mosaic of different ethnicities—much more diverse than the popular image of Israelis as mostly European in origin. While this was once true—when Israel was founded in 1948, the vast majority of its Jewish citizens were of European origin—over time, due largely to immigration, Israel’s population has significantly grown and diversified. It is now more than ten times larger than it was in 1948, and more than half of the country’s Jewish population is of at least partial Middle Eastern or North African origin. Nowadays, Israeli Jews are roughly divided between those of European descent (Ashkenazim) and those of Middle Eastern or North African descent (Mizrahim, i.e., “Eastern” Jews, sometimes also called Sephardim). Due to increasing intermarriage between the two ethnic groups, many younger Israeli Jews are of mixed Mizrahi-Ashkenazi ancestry.

Another major change in Israel’s population over the years is the growing number of native-born Israelis (called Sabras in Hebrew). When the state was established, most of its citizens were foreign-born, with only 35 percent of its Jewish citizens actually born there. In 2017, by contrast, around three-quarters of Israelis were born in Israel, more than half of them to parents who were also born in Israel. Israeli society, therefore, is no longer the predominantly immigrant society it once was. Successive waves of mass Jewish immigration from around the world transformed Israeli society, beginning in the immediate aftermath of the state’s founding when the population more than doubled with the arrival of roughly 700,000 Jews from war-torn Europe, most of them Holocaust survivors, and Jews from Libya, Yemen, and Iraq. This was followed by the immigration of Jews from other Arab countries (mainly, Morocco, Tunisia, and Egypt) in the 1950s and 1960s, and later Jews came from Ethiopia and the Former Soviet Union.

School children wave Israeli flags at the Western Wall, the holiest place where Jews can pray, in Jerusalem’s Old City, during Jerusalem Day celebrations, Wednesday, May 24, 2017. Israelis commemorated the capture of the city’s eastern sector in the 1967 Mideast war. Photo Credit: Ariel Schalit / AP.

The demographic makeup of Israeli society has changed considerably over the past seven decades of Israel’s existence. Who Israelis are, in other words, is quite different today than who they once were. They used to be mostly European immigrants; now they are mostly Israeli-born and ethnically mixed. What has not changed, however, is the fact that most Israelis are Jewish (75 percent), whether or not they are religious.

Around 21 percent of Israeli citizens are Arab (roughly 2 million people in total). Israel’s Arab population, like its Jewish population, is diverse. It is composed of different religious and ethnic groups—principally, Muslims, Christians, Druzes, and Bedouins—each with its own distinct sense of identity.

Arab citizens of Israel have the same democratic rights as Israeli Jews—for instance, they can vote for and are elected to the Knesset, they serve as mayors and judges, and they freely express their views and practice their own religion—but they have suffered from discrimination and neglect by the state.

3. Who are the Palestinians?

It is impossible to understand the Israeli-Palestinian conflict without recognizing the simple fact that Palestinians see themselves as a nation. Unlike many nations, the Palestinians do not have a state of their own. Their collective demand for statehood is one of the driving forces of the conflict, but this does not mean that they lack a national identity. Palestinian national identity has developed despite the fact that Palestinians are stateless and geographically dispersed. In fact, the condition of statelessness, dispersal, and exile has been central to the formation and definition of Palestinian national identity. In this respect, Palestinian identity is like Jewish identity, which has also been shaped by the experience of exile, dispersion, and statelessness. A massive tragedy and collective trauma is also central to the definition of Palestinian identity and modern Jewish identity. For Palestinians, it is what they call Al-Nakba (“the catastrophe” in Arabic), referring to the forced displacement and dispossession of Palestinians in 1948; for Jews, it is the Holocaust (Ha-Shoah in Hebrew, which actually also means “the catastrophe”). But unlike Jewish identity, which is millennia old, Palestinian identity is comparatively new. It is a modern identity, not an ancient one. Before the twentieth century, there was no Palestinian national identity, which is why some people continue to dispute the existence of a Palestinian nation.

The modernity of Palestinian nationalism does not discredit it. Nationalism itself is a modern cultural and political phenomenon, dating back to the end of the eighteenth century. Before then, there were no “nations” as we identify them today (although scholars of nationalism have argued that some modern nations grew from premodern ethnic groups). It was not until the nineteenth century that people began to think of themselves and others as members of different nations. In many parts of the world, this didn’t happen until even more recently, as new states were formed from the rubble of European empires. Most of the states and nationalities of the Middle East (such as Syrians, Lebanese, Jordanians, and Iraqis) emerged during the first half of the twentieth century, as products of, and in reaction to, British and French colonialism in the region. The same was true for Palestinians, although their nationalism arose in response to the emergence of other local Arab nationalisms as well as in resistance to Zionism and British colonialism (the extent to which Palestinian nationalism was a reaction to Zionism is a subject of scholarly debate). Thus, the Palestinian nation, like many nations, is a modern creation. This should not call into question its legitimacy or authenticity. It exists simply because large numbers of people identify as Palestinians.

Palestinians smile during a celebration to mark the 47th anniversary of the Fatah political movement in Ramallah, West Bank, January 4, 2012. Fatah is the political party of Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas and the late Yasser Arafat. Photo Credit: Debbie Hill/UPI/Shutterstock (12357168c).

While it is possible to date the first stirrings of Palestinian nationalism back to the mid-nineteenth century—when the local population in Palestine rebelled in 1834 against the occupying Egyptian army that had invaded the region a few years earlier—the population did not identify as Palestinians throughout the nineteenth century.

The first time that a distinct Palestinian identity was articulated was in the pages of Arabic-language newspapers published in Ottoman Palestine in the years immediately before World War I (one such newspaper, founded in 1911, was called Filastin [Palestine]). Palestinian nationalist organizations were formed during the war, and once it ended and the Ottoman Empire collapsed, the first Palestinian-Arab Congress took place in Jerusalem in 1919.

The Palestinians are a distinct nation within a much larger transnational Arab community that is composed of many different nationalities. To be sure, this was not always the case. A century ago, when Palestinian nationalism was just emerging, most Palestinians did not think of themselves as a separate nation but as members of an Arab nation. Arab nationalism was initially much stronger than Palestinian nationalism and has at different times subsumed it (especially during the heyday of pan-Arabism in the late 1950s and early 1960s). Gradually though, Palestinian nationalism has replaced Arab nationalism in the hearts and minds of most Palestinians, especially since 1967. As a result, Palestinians today have their own national identity and their own national aspirations—aspirations that remain unfulfilled. Acknowledging these aspirations is crucial to understanding what motivates the Palestinians and why they are in conflict with Israel.

4. Who was there first?

At the heart of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict are the competing claims of two peoples to the same small piece of land. Each side justifies its claim at least partly on the grounds of prior residence in the disputed territory—insisting that they are indigenous to the land, that they lived there first, and that the other is essentially a foreign intruder.

The Palestinian narrative begins in the latter half of the nineteenth century, when the territory was under Ottoman rule and Arabs constituted the vast majority of the population (more than 90 percent). The sudden arrival of masses of European Jews beginning in the 1880s and continuing over subsequent decades is presented in this narrative as an unwelcome, foreign intrusion. In this narrative, then, the Palestinian Arabs are the local, indigenous population—and hence the rightful owners of the land—and the Jews are foreigners with no right to be there.

In stark contrast to the Palestinian narrative, the mainstream Israeli-Jewish narrative presents the Jewish people as the indigenous population and the Arabs as the foreign invaders. This narrative begins about three thousand years before the Palestinian narrative, going all the way back to when the ancient Israelites (also known as the Hebrews)—who are supposedly the descendants of the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob and the ancestors of today’s Jews—conquered the land of Canaan, a land that they believed had been divinely promised to them.

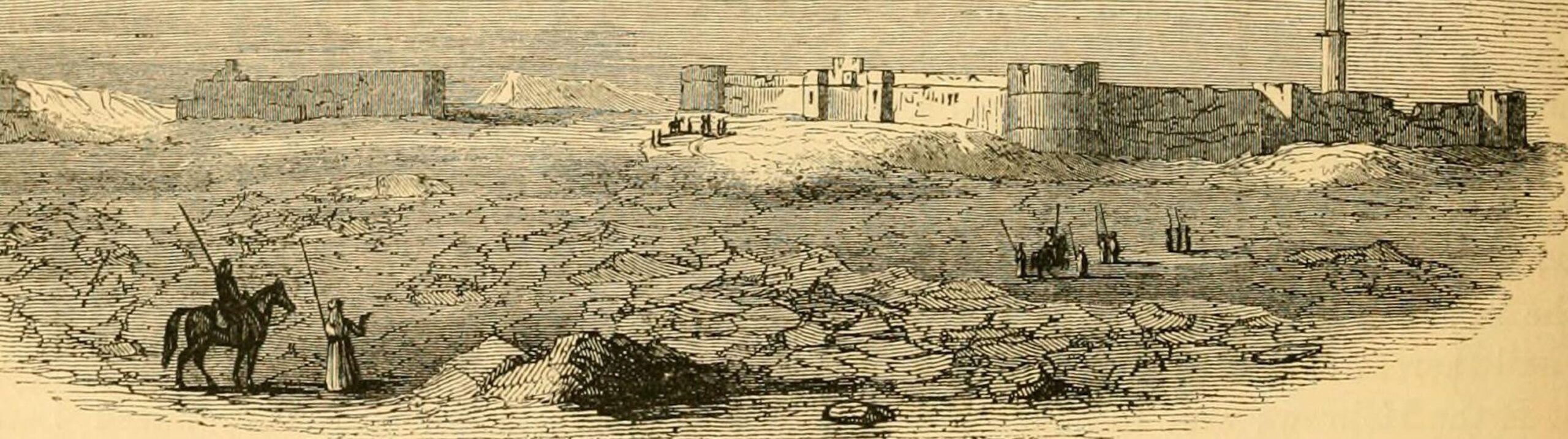

The pictorial history of Palestine and the Holy land. Photo Credit: The Reading Room / Alamy Stock Photo.

Neither of these narratives is simply false, but both are one-sided and selective (as national narratives tend to be). There is plenty of evidence that Arabs largely populated the land for many centuries, since an influx of Arab tribes from the Arabian Peninsula settled in the area during and after the Muslim conquest in the mid-seventh century. There is also textual, archaeological, and even genetic evidence to support Jewish roots in the area, dating back over thousands of years. It is impossible to definitively know who was there first since both sides claim to be the descendants of peoples who inhabited the region in antiquity.

Both Jews and Palestinians may, in fact, be partially descended from the Canaanites, who are the earliest known inhabitants of the area, entering it around 3000 BCE. Indeed, recent genetic studies have found a substantial genetic overlap between most Jews and Palestinians, suggesting that they are genetically related.

In any case, it is ultimately beside the point—what matters is that both sides genuinely believe they are entitled to the land.

5. What is Zionism?

Zionism is a modern phenomenon, the product of specific historical circumstances and currents of intellectual thought. It was born in nineteenth-century Europe in response to the two major challenges facing European Jewry at the time: antisemitism and assimilation. The former threatened the physical survival of Jews, while the latter threatened their cultural survival. Zionism claimed to be a solution to both of these threats, and it was embraced by growing numbers of Jews for this reason (although only a small minority of Jews became Zionists before World War II).

Probably the only belief that all Zionists have in common is that Jews should live in their ancestral homeland, the Land of Israel. There is no agreement among Zionists, however, about whether all Jews should live in the Land of Israel, why they should live there, and what they should actually do there—all these questions are still topics of ongoing debate.

Nevertheless, for Jews, at least, Zionism can be defined as a type, or subset, of Jewish nationalism, based upon four fundamental claims: (1) Jews are a nation; (2) all nations have a right to national self-determination (i.e., to govern themselves); (3) Jews should exercise their right to national self-determination in the Land of Israel, their national homeland; and (4) to achieve this, Jews in the diaspora (or in “exile” in classic Zionist terminology) should return en masse to the Land of Israel (“ingathering of the exiles”).

David Ben Gurion, who was to become Israel’s first Prime Minister, reads the Declaration of Independence May 14, 1948 at the museum in Tel Aviv, during the ceremony founding the State of Israel. Photo Credit: Melery821976 via Wikimedia Commons.

Since 1948, the meaning of Zionism has changed, both in Israel and in the Jewish diaspora. For many Jews, it has now simply come to mean support for Israel’s continued existence as a Jewish state (although what that actually entails is fiercely contested). Zionism has also gradually taken on a more religious character, especially since the 1967 war. It was once an avowedly secular ideological movement (though some religious Jews participated in it). While early Zionists appropriated many words, symbols, and themes from the Jewish religious tradition, most of them were staunchly secular in their beliefs and lifestyle and often dismissive of Judaism. In recent decades, by contrast, religious Jews in Israel and the diaspora have become the most vocal and energetic adherents of Zionism, and their fusion of Zionism and Orthodox Judaism has become increasingly influential, both politically and culturally. For many of these religious Zionists, particularly those who subscribe to messianic religious Zionism, Zionism is now primarily about settling Jews throughout the Land of Israel, especially in the region of Judea and Samaria (the West Bank), where most of the stories of the Bible took place. For them, Zionism today is less about Jewish self-determination and more about fulfilling God’s commandments and wishes.

In sum, Zionism is a diverse and dynamic set of beliefs. It has been adapted to different contexts and redefined in different eras. This helps explain not only why Zionists frequently disagree among themselves but also why Zionism has endured and been so successful.

6. Was Zionism a form of colonialism?

The most persistent, and perhaps most common, criticism of Zionism is that it is another instance of European colonialism. Palestinian and Arab nationalists have continually leveled this charge against Zionism, and many supporters of the Palestinian cause around the world have echoed it. Indeed in left-wing circles in Western societies, and especially on university campuses and in academia, it has become not only fashionable, but almost taken for granted, to view Zionism as synonymous with colonialism.

For most Jews, in particular, Zionism is regarded as the antithesis of colonialism. They see it as a movement of national liberation for an oppressed people, more like the anticolonial independence movements that evicted European colonial powers in the years after World War II.

Edmonton, Canada – Oct. 18, 2023. Photo Credit: Jenari / Shutterstock.

As with many of the competing claims made about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, there is some truth to both of these readings of Zionism. In theory, Zionism was akin to a national liberation movement for Jews, who were undoubtedly oppressed in Europe. It also had to contend with imperial powers, initially the Ottoman Empire and then the British Empire. But unlike other national liberation movements, or nationalist movements in general, Zionism required the mass relocation and resettlement of Jews to an area (Palestine) that was inhabited by another population (Arabs). In doing so, Zionists had to justify their presence and overcome the resistance of the indigenous population, who saw them as intruders. In this respect, the Zionist project was similar to colonial projects undertaken by European settlers in North America, Australia, New Zealand, Algeria, Brazil, and South Africa. In these cases of what scholars term “settler-colonialism,” European settlers established colonies and built new societies, largely modeled on the ones they had left behind. Although they frequently claimed that the “natives” would benefit from their presence since they brought progress and “civilization” to them, in reality the indigenous population ended up being dispossessed of its land, and socially and politically marginalized at best (at worst, they were simply killed off).

Like these cases of settler-colonialism, Jewish settlers came to Palestine from Europe and established a colony there. Rather than integrating with the local population, they created their own society. They tended to view their Arab neighbors with a mix of condescension, contempt, and benevolent paternalism, typical of European attitudes at the time. They harbored the same cultural prejudices as other Europeans of their era, assuming both the superiority of European civilization and the benefits it would inevitably bring to the more “primitive,” “backward” Arabs.

While Zionism shares some similarities with European colonialism, it differs in important ways, the biggest being its motives. European colonialism was generally motivated by imperialism. European states established colonies to enhance their national power, extend their cultural influence, exploit the local labor force, and extract the territory’s resources. The territory targeted for colonization was selected based upon the strategic and economic interests of the colonizing state (the “mother country”).

Zionism, by contrast, was not driven by imperialism. It was not motivated by the political, economic, or strategic interests of any European state (although it received support from some, who had their own motives). Jewish settlers were not sent to Palestine by any imperial power—in fact, they were fleeing the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires—nor were they acting on behalf of any imperial power. They did not even come from a single country. They chose to settle in Palestine not because of its strategic value or natural resources but solely because of its historic, religious, and cultural value to Jews. In fact, Zionist settlement in Palestine was expensive and unprofitable. Rather than conquering or stealing the land, before 1948 the Zionist movement legally purchased it, often at exorbitant prices, from its owners, who were mostly absentee Arab landowners (but only about 7 percent of the land in Palestine was purchased by the Zionist movement before 1948). Nor did the Zionist movement in its early years seek to eliminate, subjugate, or exploit the native population. Zionists even tried not to employ Arabs because they wanted to be self-reliant and ensure that Jewish immigrants could find work (this was, however, discriminatory and materially harmful to the Arab population). Crucially, Zionist settlers saw themselves as the indigenous people of the land, who were returning to it after a long, forced exile.

Nevertheless, from the perspective of the local Arab population, there was no difference between Zionist colonization and European colonialism, especially after the British gave their support to the Zionist movement and conquered Palestine. In the eyes of the Arabs, the Jewish settlers were just the latest in a long line of foreign invaders, and their arrival was part of the same process of European imperialism that had been occurring in the Middle East throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Such a view, though inaccurate, is completely understandable in the context of that time.

7. Why did many Palestinians become refugees?

There have long been two diametrically opposed explanations for why 700,000 or so Palestinians became refugees during the course of the 1948 war, which Israeli Jews call their “War of Independence” and Palestinians refer to as the Nakba— or catastrophe.

The Palestinians and their supporters insist that the refugees were violently expelled by Zionist and later Israeli armed forces, who systematically carried out a centrally directed and organized campaign of “ethnic cleansing” to create an ethnically pure Jewish state (i.e., one devoid of Arabs).

In stark contrast, according to the traditional, mainstream Israeli explanation, the Palestinians fled or chose to leave their homes because they were encouraged, and sometimes even ordered, to do so by their own leaders and by outside Arab leaders.

Both of these competing accounts of the origins of the Palestinian refugee problem are one-sided and tendentious. Their purpose is to assign blame, or avoid it, rather than offer a more accurate and complicated explanation for how and why Palestinians became refugees in 1948.

Arab refugees stream from Palestine on the Lebanon Road, Nov. 4, 1948. These are Arab villagers who fled from their homes during fighting in Galilee between Israel and Arab troops. Photo Credit: Jim Pringle / AP.

Relying upon extensive documentary evidence, Israeli historian Benny Morris’s research showed that Palestinians did not generally leave because they were encouraged or ordered to do so by Palestinian or Arab leaders (except, notably in the case of the Palestinian inhabitants of the city of Haifa), as generations of Israelis had been told. Many Palestinians were, in fact, violently expelled by Zionist and Israeli troops, just as the Palestinian narrative maintains.

Whether or not it was premeditated or planned, the expulsion of Palestinian civilians by Zionist and Israeli forces was a war crime according to international law. Palestinian and Arab forces also expelled Jewish civilians from areas that they conquered, and both sides committed various other kinds of war crimes (such as massacring civilians, raping women, and summarily executing prisoners of war).

Most Palestinian refugees were probably not expelled, but they fled out of fear and panic, as civilians often do in war. As this fear and panic spread like a contagion, and was also sometimes deliberately induced and encouraged, it contributed to the collapse of Palestinian society, which, in turn, led to a mass exodus (the departure of many middle- and upper-class Palestinians during the early stages of the civil war also contributed to this exodus, as did a lack of centralized leadership). In short, widespread fear gave rise to mass panic and then mass flight. Once this was underway, in the latter half of the war, Israel’s leadership, particularly Ben-Gurion, welcomed it as an opportunity to reduce Israel’s Arab population.From June 1948, the Israeli government’s official policy was to prohibit the return of refugees to the country. From that point onward, Israel barred Palestinian refugees from returning, forcefully prevented them from doing so, razed hundreds of their abandoned villages, and appropriated their homes and lands.

Ultimately, therefore, Israel bears at least partial responsibility for the Palestinian refugee problem. But so too do the Arab states that attacked Israel in 1948 as well as the Palestinian leadership, whose rejection of the UN’s partition plan in November 1947 led to the outbreak of the war.

8. What are the main issues that need to be resolved in an Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement?

There are four main issues that have bedeviled peace talks and are the chief obstacles to reaching a comprehensive peace agreement:

(1) The future of the contested city of Jerusalem

The future of Jerusalem has been the most contentious and challenging of all the issues in the peace talks between Israel and the Palestinians. The city’s historical and religious significance to Jews, Muslims, and Christians worldwide makes it a particularly highly charged issue at the negotiating table.

Israelis and Palestinians both want Jerusalem as their national capital. It has been Israel’s self-declared capital since 1949, although only the United States and a few other countries officially recognize this (U.S. President Donald Trump controversially announced this recognition in December 2017). The PLO no longer claims all of Jerusalem for a Palestinian capital. It now limits its territorial claim to East Jerusalem, which it regards as occupied Palestinian territory (as does the UN). For decades, Israeli leaders categorically rejected this claim, insisting that “Jerusalem is the eternal, undivided capital of Israel,” and vowing never to divide it. Although Israeli politicians still frequently repeat this phrase, in negotiations with the Palestinians Israeli leaders have actually been willing to accept Palestinian sovereignty over parts of East Jerusalem.

Bill Clinton, Yitzhak Rabin, Yasser Arafat at the White House, September 1993. Photo Credit: Vince Musi / The White House.

It is quite conceivable that an agreement could eventually be reached to allow the Palestinian neighborhoods of East Jerusalem to become the capital of a Palestinian state, while West Jerusalem and the Jewish neighborhoods of East Jerusalem would be Israel’s capital.

An even more difficult challenge arises when it comes to the Old City of Jerusalem, an area less than one square kilometer in size that is packed with historical and religious sites, including Judaism’s holiest site (the Temple Mount) and, sitting on top of it, Islam’s third-holiest site (the Haram al-Sharif). The Old City is also home to a few thousand Jews and more than 30,000 Palestinians, and it attracts hordes of foreign tourists, making it a lucrative asset for Israel or for a future Palestinian state. Both sides want sovereignty over the Old City, and especially over the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif. The Camp David summit collapsed primarily because neither side was willing, or even able, to give up its claim to this sacred space (Arafat allegedly feared that he would be assassinated if he accepted Israeli sovereignty over the Haram al-Sharif). Since then, some creative proposals have been made to divide the Old City and give both sides, or neither side, sovereignty over the fiercely contested Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif, but none of these proposals have been accepted by Israeli or Palestinian leaders.

(2) The fate of Palestinian refugees

If giving up sovereignty over some of Jerusalem will be the hardest concession that Israelis will have to make, then giving up an unqualified “right of return” for Palestinian refugees will probably be the hardest concession for Palestinians. For them, the issue of Palestinian refugees is the most emotional of all the final-status issues because it concerns what Palestinians call the Nakba, the national tragedy that happened to them when Israel was founded in 1948, which is still central in the collective memory and national identity of Palestinians.

Palestinians believe that the right of return for Palestinian refugees is not only morally justified—since they blame Israel for deliberately and systematically expelling Palestinian civilians during the war, and then forcibly preventing them from returning to their homes and villages after the war—but also legally mandated by international law. In particular, they insist that the right of return was established in UN Resolution 194, passed in December 1948, which, among other things, stipulated that “the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbors should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date” (this has been reaffirmed in multiple UN resolutions since then).

Israeli governments, left and right alike, have always adamantly rejected a right of return for Palestinian refugees on the grounds that Israel is neither morally responsible for their original displacement nor legally required to admit them, let alone their descendants (who should not be considered refugees, according to Israel, since this status should not be inherited).

Israel has a major objection to a right of return for Palestinian refugees—it fears that this could lead to the demise of the Jewish state. There are now 5.4 million Palestinians registered as refugees by the UN agency that still looks after them (the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees, or UNRWA). At least two million more Palestinians, scattered around the world, claim to be refugees, putting the total number somewhere between seven and eight million people. Israel’s Jewish population is around 7 million, so if Palestinian refugees were entitled to live there, the country’s demographics could be completely upended. Palestinians could quickly outnumber Jews (there are already roughly 2 million Palestinian citizens of Israel), and then simply vote the Jewish state out of existence. Even if this nightmare scenario for Israeli Jews is unlikely to happen, a large influx of Palestinians could severely strain the already fragile relationship between Jews and Arabs in Israel and pose a potential security risk. Hence, Israel argues that because of these demographic and security concerns it would be very dangerous, if not suicidal, to allow potentially hostile refugees to return en masse.

On the face of it, the dispute over this issue seems irresolvable, dooming any attempt to negotiate a peace agreement. However, in the actual negotiations that have taken place, both sides have displayed more flexibility than their public postures, and propaganda, would suggest. In the same way that Israeli leaders have been willing to compromise in negotiations behind closed doors on the hot-button issue of Jerusalem, Palestinian leaders have been willing to compromise on the refugee issue. While insisting upon a Palestinian right of return in principle, they have conceded that this will be restricted in practice.

(3) The borders of a future Palestinian state

Having abandoned their claim to the vast majority of the land they believe is rightfully theirs (amounting to 78 percent of Mandate Palestine)—which Palestinians regard as a massive concession—the PLO, and most Palestinians, have been strongly opposed to making any more territorial concessions. Both Arafat and Abbas have insisted that the future border between Israel and a new Palestinian state runs along the “Green Line”—the 1949 armistice line that was drawn on a map with a green marker at the end of the first Arab-Israeli war (which then served as the de-facto border between Jordan and Israel until the 1967 war). Since Israel captured the West Bank from Jordan in the 1967 war, Israeli governments, and a majority of Israelis, have consistently opposed withdrawing back to the Green Line for a variety of reasons. The most commonly cited objection has been that Israel needs “defensible borders” because of the security threats it faces. The Green Line, it is argued, is not a defensible border since it would put Israeli population centers within easy reach of Arab armies and, more recently, rockets and missiles. Israeli governments have also argued that the existence of numerous Jewish settlements in the West Bank— where as many as 470,000 Israelis now live—makes it almost impossible for Israel to completely withdraw from the territory. The political, social, and economic cost of dismantling these settlements and evacuating all their residents would be prohibitive for any Israeli government. Hence, Israeli leaders have insisted that the future border between Israel and a Palestinian state must be drawn in a way that allows most of the settlers to stay where they are. Since the vast majority of settlers live in sprawling, densely populated blocs of settlements located near the Green Line—in areas adjacent to urban areas within Israel (these settlements are like suburbs of Israeli cities)—Israel wants to annex these large “settlement blocs.”

The West Bank and Gaza Strip are regarded as occupied territories under international law because they were not part of Israel before the June 1967 war, when the Israeli army conquered them. Israel took the West Bank from Jordan and the Gaza Strip from Egypt; it also captured the Golan Heights from Syria, which it still occupies, and Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, which it later returned after making peace with Egypt.

While it is true that Israel did not go to war in 1967 to conquer these territories, that Israelis believe the war was forced upon them, and that the West Bank (Judea and Samaria) is of great historical and religious importance to Jews, these factors are irrelevant in terms of international law.

Nor does it matter whether or not Israel’s military occupation is “benevolent,” as many Israelis once believed it to be (until the First Intifada disabused them of this reassuring belief). All that matters legally is that Israel conquered the West Bank and Gaza Strip and that territorial conquest is forbidden by international law (this was not the case before the twentieth century).

(4) Security

Most Israelis would probably support an Israeli withdrawal from the West Bank if they were not so worried, quite understandably, about the security threats that could follow it. Foremost in their minds is the threat of Hamas taking over the West Bank—as it has already done in Gaza following Israel’s withdrawal in 2005.

The risk that a future Palestinian state could collapse into disorder and civil strife, which would surely spill over into Israel, also worries Israelis as they have recently witnessed the collapse of Arab states (Syria, Libya, and Yemen) and the horrific violence that resulted. Along with this potential threat, there is the risk that jihadist terrorist groups (specifically, the Islamic State and Al Qaeda) could infiltrate, find sanctuary in, or even overrun a weak or failed Palestinian state, as has happened in recent years in Iraq, Yemen, and neighboring Syria and Egypt (in its Sinai region). Indeed, nowadays Israelis are more worried about whether Palestinian security forces could maintain order and stability in the West Bank in the aftermath of an Israeli withdrawal than whether they will attack Israel.

9. Is a two-state solution still possible?

A two-state solution to the century-old conflict over Palestine has been recommended for more than eight decades. For a short period in the early 1990s, hopes were raised that a two-state solution was finally within reach, but the assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, the collapse of the Oslo peace process, and the Second Intifada dashed these hopes. Since then, as the conflict has dragged on interminably, with periodic eruptions of large-scale violence, the prospects for a two-state solution have grown dimmer.

Nowadays, few people still believe that a two-state solution is imminent, and they are often dismissed as naïve or ignorant. What once seemed inevitable now seems implausible, at least for the foreseeable future. Policymakers, diplomats, and experts warn that the window of opportunity for a two-state solution is closing. Some believe that it has already closed due to the “facts on the ground,” particularly the presence of ever-expanding Israeli settlements in the West Bank and East Jerusalem that now house over 650,000 settlers.

Flags of Palestine and Israel against the sky and old Jerusalem. Photo Credit: Melnikov Dmitriy / Shutterstock.

Growing pessimism about the possibility of a two-state solution is, sadly, well-founded. Although it is still technically feasible, it is highly unlikely. For a two-state solution to work—that is, to peacefully resolve the conflict—it has to be mutually agreed upon, publicly accepted, and successfully implemented. It is difficult to achieve just one of these requirements, let alone all three.

The first challenge is to resume peace talks since there is really no substitute for them. Although the “State of Palestine” is now officially recognized by most states in the world and, since 2012, has observer status in the UN (but not full membership), it exists more on paper than in reality. To become a reality and give Palestinians actual sovereignty, Israel has to voluntarily relinquish its direct or indirect control over most of the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip. While some hope that Israel can be coerced into doing so, whether by Palestinian violence, diplomatic pressure, or the grassroots Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) campaign against it, the strength of Israel’s economy and the power of its military means that coercion alone probably won’t succeed (regardless of whether or not it is justified).

Even if, as seems likely, there is mounting international pressure on Israel to end its occupation of Palestinian territories, the international community is unlikely to marshal sufficient pressure to effectively force Israel to grant Palestinians what it has so far been unwilling to give them at the negotiating table—especially if the U.S. government continues to back Israel diplomatically and financially. Moreover, international pressure on Israel could easily backfire and only encourage Israeli defensiveness and defiance, as some observers believe is already happening.

A negotiated peace agreement, therefore, remains the best means to achieve a sustainable and lasting two-state solution to the conflict. But after almost three decades of diplomacy and intermittent negotiations, neither side is currently interested in engaging in serious peace talks.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has no interest in resuming peace talks. Deeply distrustful of the Palestinians and disdainful of their leadership, he has always been at best skeptical about the peace process (in the early 1990s, he was an outspoken critic of the Oslo Accords).

Palestinian Authority (PA) President Mahmoud Abbas has long been a staunch advocate of the peace process, but his enthusiasm for peace talks seems to have been exhausted. Aging and unwell—he is in his late-eighties—Abbas is now preoccupied with staying in power and sidelining potential political rivals.

Israeli-Palestinian peace talks, therefore, are highly unlikely to resume in the near future, if at all. At a minimum, there will have to be a change in Israeli and Palestinian leadership. But whenever this eventually happens, there is no guarantee that whoever succeeds Netanyahu and Abbas will be more receptive to serious peace talks or, for that matter, more willing to compromise during them.

Even if the peace process is not yet dead and could somehow be resuscitated, with new leaders in Jerusalem and Ramallah, there is no reason to expect that the outcome of future peace talks would be any different than that of past rounds of negotiations. The track record of negotiations demonstrates that it is an enormous challenge for Israelis and Palestinians to reach a comprehensive peace agreement. Both sides will have to make some significant, emotionally painful, and politically unpopular compromises

While most Israelis and Palestinians could probably be persuaded to vote in favor of a peace agreement in referendums, a sizable minority (roughly a third) on both sides can be expected to reject any agreement involving a territorial compromise. On both sides, the most dogmatic of these rejectionists are religious extremists, specifically, hardline religious Zionists and Palestinian Islamists who sanctify the land, claim exclusive possession of it, and believe that their religion forbids them from ever ceding ownership over any part of it. Since the holy status of the land means that it cannot be traded away or partitioned, according to this view, any kind of two-state solution is illegitimate and unacceptable. By no means do all religious Zionists and Palestinian Islamists hold such hardline views, but those that do have already demonstrated that they are willing and able to disrupt efforts to make peace (such as when they acted as “spoilers” during the Oslo peace process). It is highly likely, therefore, that they will attempt to obstruct the implementation of a two-state solution, possibly by any means necessary, including violence.

10. Is any other proposed solution possible?

“One-State”

As the peace process stalled and then broke down, and Israeli settlements continued to expand, Palestinian intellectuals, academics, and activists, many of them living in the diaspora (most notably, the late Edward Said), have renewed calls for a one-state solution. For some of its Palestinian advocates, a one-state solution was always preferable to a two-state solution because they believed the latter would not deliver justice for Palestinians. A two-state solution would not enable all Palestinian refugees to realize their “right of return” or reclaim their lost land and property (since Israel would never accept this). Nor would it end discrimination against Israel’s Palestinian citizens, and could make matters worse for them by reinforcing ethnic separatism. A one-state solution, on the other hand, could potentially satisfy the needs and aspirations of all Palestinians, not just those living in the West Bank and Gaza. Hence, it has long been seen by some Palestinians, and by some of their supporters, as the most just solution to the conflict. For other Palestinian proponents of a one-state solution, it is simply the only remaining solution because they have lost hope for the establishment of a viable, contiguous, and sovereign Palestinian state alongside Israel.

The one-state solution’s main appeal lies in the fact that it acknowledges that there is already one state—Israel—effectively in control of the entire territory between the Mediterranean and the Jordan River. Instead of trying to change this existing “one-state reality” by creating a separate, mini-state for Palestinians, to many it seems much easier to give all Palestinians living under Israel’s de facto rule (specifically, those in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza) the same rights as Israeli citizens, particularly the right to vote in Israel’s national elections. A one-state solution, in other words, could be peacefully achieved through granting citizenship, equal rights, and democratic representation to everyone living under Israeli sovereignty. A peace agreement, which has proven to be so elusive, will not be necessary in this scenario. Israelis and Palestinians will not have to divide Jerusalem, delineate borders, or deal with many other complex and thorny issues that have bedeviled negotiations for a two-state solution. They just have to accept the basic democratic principle of “one person, one vote.”

However alluring this idea sounds to many Westerners, it has little popular appeal among Palestinians and Israeli Jews because it conflicts with their national aspirations. They both want their own states in order to fulfill their collective desires for national self-determination. There is, however, growing support for a one-state solution among a younger generation of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza, many of whom are politically alienated from the Palestinian leadership (both Fatah and Hamas), economically and socially frustrated due to a lack of suitable employment opportunities, and disillusioned with the idea of Palestinian statehood because they expect a future Palestinian state will be corrupt and authoritarian (like the PA). Roughly a third of the Palestinian population in the West Bank and Gaza is between the ages of 15 to 29, so if this trend continues and more and more young Palestinians embrace a one-state solution, then the Palestinian public as a whole will gradually become more supportive of it.

But it is extremely unlikely that the Israeli-Jewish public will ever support a one-state solution, at least not a genuinely democratic one. A democratic one-state solution will not necessarily prevent Palestinians from exercising their right to national self-determination since they will eventually make up the majority of the population (given their higher birth rates). Israeli Jews, by contrast, will become a minority, whose rights and security will be dependent upon the will of the Palestinian majority. The millennia-long history of Jewish persecution, the century-long history of the Arab-Jewish conflict, and recent Middle Eastern history all give Israeli Jews ample reason to fear such a scenario. Indeed, for the vast majority of them, the whole point of Zionism was to give Jews a state of their own in which they could live safely and be masters of their fate. Having secured Jewish sovereignty, at great cost, Israeli Jews are not going to voluntarily give it up, and put themselves at the mercy of Palestinians who they fear and distrust. As far as they are concerned, accepting a democratic one-state solution is tantamount to national suicide.

“A Confederation”

Many creative ways to resolve the conflict have been proposed in recent years as alternatives to the conventional two-state and one-state solutions. The most promising combines elements of both solutions. It envisages two sovereign states, Israel and Palestine, who are part of a “confederation” (like the member states of the European Union). This would entail joint governance in some areas (such as managing the environment and shared natural resources like water), and extensive cooperation on certain issues of mutual concern (like security and economic matters). After a transitional period, the two states would have an open border between them, providing freedom of movement for their populations that would enable people in both states to come and go (whether for work, studying, socializing, shopping, or praying at their holy sites). It also envisions a united, not divided, Jerusalem as the shared capital of both states, with its municipal affairs run by a joint Israeli-Palestinian authority representing and serving all of the city’s residents, and its holy sites managed by religious authorities and international bodies to guarantee access for all.

Photo Credit: Saskia Keeley via Friends of Roots

Instead of seeking separation, a confederal approach promotes interaction and integration, but in a mutually agreed-upon and gradual fashion—unlike a one-state solution that compels the two sides to cohabit and share power. In other words, the conventional two-state solution proposes a divorce (and a division of assets) between Israelis and Palestinians, a one-state solution proposes an arranged marriage (or even a forced one), and a confederal solution suggests they cohabit and form more of a partnership between housemates. Another important distinction between this approach and the conventional two-state and one-state solutions is the delinking of citizenship and residency. In a confederation, each state would have its own citizenship policies (including laws of return), but citizens of one state could be permitted to live as residents in the other (much like citizens within the EU), with each state setting limits on the number of noncitizens granted residency. Thus, Israeli citizens would be able to live in Palestine, and Palestinian citizens could live in Israel. In both cases they would be residents, but not citizens (Palestinian citizens of Israel would keep their Israeli citizenship, but could perhaps, if they wished, have dual citizenship). Delinking citizenship and residency could help resolve two of the biggest issues that have bedeviled peace talks, and made a two-state solution so hard to achieve: the Palestinians’ insistence on a “right of return” for their refugees that would allow some of them to move to Israel if they wished; and Israel’s reluctance to remove large numbers of Jewish settlers from the West Bank, especially those who are most determined to stay. In a confederation, if Palestinian refugees want to live in Israel, they could do so as residents while exercising their full citizenship rights, such as voting in national elections, in Palestine. This would alleviate Israeli Jewish fears that they would be swamped by “returning” Palestinian refugees whose numbers would give them an ability to simply vote the Jewish state out of existence. Similarly, if Jewish settlers want to stay in the West Bank, they could do so as residents of a Palestinian state, as long as they are law-abiding and peaceful.

A confederal solution offers a way to overcome some major obstacles—concerning Jerusalem, Palestinian refugees, and Jewish settlers—that stand in the way of a two-state solution. But also, by proposing joint institutions to facilitate ongoing cooperation between the two states, especially concerning their security and economic development, a confederal solution is more likely to ensure that a future Palestinian state is prosperous and stable, whereas there is a serious risk that it could become a failed state if simply left to fend for itself under a conventional two-state solution. A confederal solution will also be fairer and more democratic than any likely one-state outcome. Though it may seem far-fetched, in some respects a confederal solution is actually a more realistic approach to resolving the conflict than either of the main options (i.e., two-state or one-state solutions).

Complete answers to these questions and more appear in Dov Waxman’s The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: What Everyone Needs to Know.

Have a question not answered here? Send us an email.