Executive Summary

Rising obesity rates in the U.S. are not just cause for concern about the overall health of the general public. Experts say that obesity will constitute a national security crisis if the military is unable to reach the staffing levels necessary to operate properly.

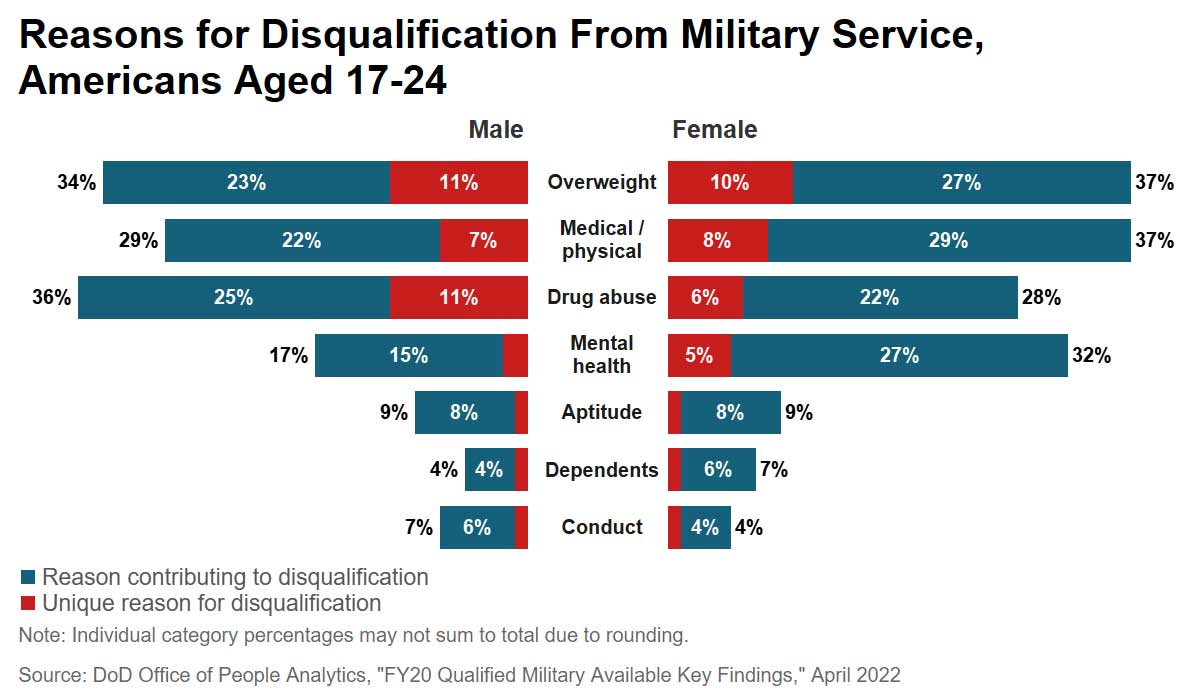

The latest figures show a national adult obesity rate of 41.9%. The growing obesity epidemic in the United States has resulted in a dwindling recruitment pool of people fit for military service. In 2020, 35% of Americans between the ages of 17 and 24 were ineligible for enlisting in military service at least in part due to obesity, and 11% were disqualified solely due to their weight. In 2022, the U.S. Army fell 25% below its recruitment goals, and obesity constituted the largest single disqualifying factor among all military recruits for that year.

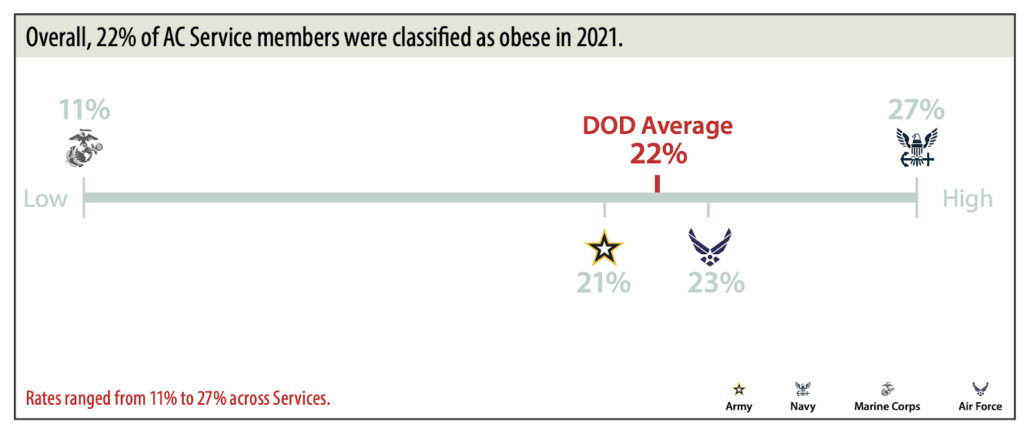

The overall prevalence of obesity among all active service members in 2021 was 22% — a 12% increase from 2020. Obesity was higher among male (22.5%) as compared to female service members (17.4%), and among older as compared to younger service members. The Navy had the highest prevalence of obesity at 27%, while the Marine Corps had the lowest at 11%. Overweight or obese soldiers are at higher risk for injury and illness. Every year, the Department of Defense (DoD) spends about $1.5 billion on replacing unfit service members and obesity-related healthcare costs.

These findings are alarming because the country’s defense system is predicated on maintaining a steady number of military recruits, active-duty personnel and reservists. From 2010 to 2020, the Air Force (<-1%), Army (-14.4%) and Marine Corps (-10.7%) all experienced a decrease in recruits. Only the Navy had an increase in numbers (+5.8%), likely in part due to implementing an online recruitment system prior to COVID-19. The U.S. military may find itself unable to carry out expected missions if current trends continue.

This report examines how the obesity epidemic has impacted the U.S. military, how the DoD has attempted to address weight standards among military personnel, and concerns about the initiatives implemented to overcome this challenge.

Obesity in the US

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines obesity as occurring when an individual’s weight is higher than what is healthy for their height. BMI (body mass index) is a tool commonly used to screen for obesity based on height and weight. An individual with a BMI of 30 or higher is considered obese, while a BMI between 25 and 29.9 is considered overweight rather than obese. CDC, “Adult Body Mass Index,” cdc.gov, June 3, 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/basics/adult-defining.html. BMI is based on the following formulas: weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared, or weight in pounds divided by height in inches squared and multiplied by a conversion factor of 703. For more information, see CDC, “About Adult BMI,” cdc.gov, June 3, 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html#Interpreted

(Experts note that BMI is not a perfect tool because it measures excess weight as opposed to actual body fat, and it fails to differentiate between fat, muscle and bone mass. According to the CDC, factors such as age, sex, ethnicity and muscle mass could impact the relationship between BMI and actual body fat.)Department of Health Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Body Mass Index: Considerations for Practitioners,” cdc.gov (accessed June 24, 2023), https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/downloads/bmiforpactitioners.pdf

Obesity rates among the general U.S. adult population have been increasing at alarming rates, and the overall prevalence of obesity among adults increased by 37% in the first two decades of the 21st century.CDC, “Overweight and Obesity,” cdc.gov, The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html The latest figures show a national adult obesity rate of 41.9%.Trust for America’s Health, “The State of Obesity: Better Policies for a Healthier America 2022,” tfah.org, September 2022, https://www.tfah.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/2022ObesityReport_FINAL3923.pdf In 1990, no U.S. state reported an obesity rate higher than 14%. By 2002, no state in the U.S. had an obesity rate below 15%, and by 2010, no state had a rate less than 20%.CDC, “Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System,” cdc.gov, 2010, https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/downloads/obesity_trends_2010.pdf Between 1986 and 2000, the number of moderately obese Americans doubled (i.e. those with a BMI of 30-35). Within that same time period, the proportion of adults with a BMI of at least 40 quadrupled. Roland Sturm and Darius Lakdawalla, “Swollen Waistlines, Swollen Costs: Obesity Worsens Disabilities and Weighs on Health Budgets,” Rand Review, Vol. 28, No. 1, Spring 2004, p. 24–29, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/www/external/publications/randreview/issues/spring2004/RAND_Review_spring2004.pdf

Factors such as age, gender, ethnicity and geography factor into obesity rates. For instance, southern states have the highest prevalence of obesity (36.3%), and obesity rates are higher among adults aged 45-54 (39.3%).CDC, “Adult Obesity Prevalence Maps,” cdc.gov, March 17, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/prevalence-maps.html Non-Hispanic Black adults have the highest prevalence of obesity (49.9%), followed by Hispanic adults (45.6%). CDC, “Adult Obesity Facts,” cdc.gov, May 17, 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html Adults without a high school degree or its equivalent have the highest obesity levels (37.8%), while college graduates have the lowest levels (26.3%).CDC, “Adult Obesity Prevalence Maps,” cdc.gov, March 17, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/prevalence-maps.html According to a report by the Trust for America’s Health and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, an estimated 60% of Americans will be obese by 2030.David Vergun, “‘Grab and Go’ an Important Factor in Encouraging Healthy Eating,” defense.gov, June 14, 2019, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/1876340/grab-and-go-an-important-factor-in-encouraging-healthy-eating/

Obesity in the Military: A National Security Issue

Aside from the broader concerns for the health of the general population, rising obesity presents a significant concern for the U.S. military because it limits the qualified recruitment pool. An estimated 16% of military applicants were disqualified due to their weight in 2014, the most recent year for which this statistic was found.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, “Understanding and Overcoming the Challenge of Obesity and Overweight in the Armed Forces: Proceedings of a Workshop,” National Academies Press, 2018, https://doi.org/10.17226/25128 A 2018 study from The Citadel military college, the U.S. Army Public Health Center and the American Heart Association found that 47% of men and 59% of women in basic training failed the Army’s entry-level physical fitness test. The Citadel, “Citadel-Led Study Reveals Threat to U.S. Military Readiness Due to Unfit Recruits,” citadel.edu, January 11, 2023, https://live-the-citadel-today-cloud.pantheonsite.io/citadel-led-study-reveals-threat-to-u-s-military-readiness-due-to-unfit-recruits/

"This is a complex problem that has a deep impact on national security by limiting the number of available recruits, decreasing reenlistment candidacy, and potentially reducing mission readiness," said Sara Police, PhD, Associate Professor in the Department of Pharmacology and Nutritional Sciences at the University of Kentucky College of Medicine. She added, "Despite efforts by the US government and Department of Defense, obesity continues to impact the military and the risk to national security is great." Open Access Government, “How Does Obesity Threaten the US Military’s Mission Readiness?,” openaccessgovernment.org, May 9, 2022, https://www.openaccessgovernment.org/how-does-obesity-threaten-the-us-militarys-mission-readiness/135210/

Former military leaders have echoed the warnings about the potential impact of obesity on the U.S. military. "The military has experienced increasing difficulty in recruiting soldiers as a result of physical inactivity, obesity, and malnutrition among our nation’s youth. Not addressing these issues now will impact our future national security," said Mark Hertling, retired U.S. Army lieutenant general. "Fit and healthy service members are vitally important to the military because lives and our national security are at stake," said Richard E. Hawley, retired four-star U.S. Air Force general.CDC, “Unfit to Serve,” cdc.gov, June 20, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/resources/unfit-to-serve/index.html The CDC has produced factsheets highlighting the problem of how physical fitness impacts national security.CDC, “Physical Activity and Military Readiness,” cdc.gov, February 16, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/resources/physical-activity-military-readiness.html

Obesity has been an obstacle to military recruitment for more than 30 years, and the percentage of military-age adults who are not qualified for service due to weight has grown continuously for more than 60 years. Erin Tompkins, “Obesity in the United States and Effects on Military Recruiting,” Congressional Research Service, December 22, 2020, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/IF11708.pdf

The majority of active duty personnel are between the ages of 17 and 34 (78%), but only about 20% of the U.S. population is in a similar age bracket (19 to 34). This means that the pool of potential recruits starts out small. Kaiser Family Foundation, “Population Distribution by Age” kff.org, 2021, https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/distribution-by-age/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7DDoD, “Health of the Force 2021,” health.mil, 2022, https://amarkfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/DOD-Health-of-the-Force-2021.pdf Even more concerning is the fact that an estimated 71% of Americans aged 17 to 24 would not qualify for military service due to not meeting weight standards, physical or mental health problems, inadequate education, criminal histories or illicit drug use. Mitchell L, “Obesity Prevalence Among Active Component Service Members Prior to and During the COVID-19 Pandemic, January 2018–July 2021,” health.mil, March 1, 2022, https://health.mil/News/Articles/2022/03/01/Obesity-Prev-MSMR Other sources estimate that 77% of Americans aged 18 to 24 would not qualify for military service, mostly due weight or physical or mental health issues. Thomas Novelly, “Even More Young Americans Are Unfit to Serve, a New Study Finds,” Military News, military.com, September 28, 2022, https://www.military.com/daily-news/2022/09/28/new-pentagon-study-shows-77-of-young-americans-are-ineligible-military-service.html U.S. Army Recruiting Command, “Recruiting Challenges,” recruiting.army.mil, 2017, https://recruiting.army.mil/pao/facts_figures/ This equates to approximately 24 million young people being ineligible to serve in the U.S. military.Erica Pandey, “The Dwindling Pool of Americans Eligible for Military Service,” axios.com, February 20, 2018, https://www.axios.com/2018/02/20/the-dwindling-pool-of-americans-eligible-for-the-military-1519150735

In 2020, 35% of Americans between the ages of 17 and 24 were ineligible for enlisting in military service at least in part due to obesity, and 11% were disqualified solely due to their weight.DoD Office of People Analytics, "FY20 Qualified Military Available Key Findings,” April 2022, https://amarkfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/DOD-QMA-2020-Brief-PUBLIC.pdf

The DoD Health Related Behavior Survey (HRBS) has been conducted approximately every three years since 1980. Since 1995, the surveys have included weight statuses, including overweight and obesity rates among different military branches.RTI International, “Department of Defense Survey of Health Related Behaviors Among Active Duty Military Personnel,” defense.gov, September 2009, https://prhome.defense.gov/Portals/52/Documents/RFM/Readiness/DDRP/docs/2009.09%202008%20DoD%20Survey%20of%20Health%20Related%20Behaviors%20Among%20Active%20Duty%20Military%20Personnel.pdfSarah O. Meadows, Charles C. Engel, Rebecca L. Collins, et al., “2018 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS) Results for the Active Component,” rand.org, 2021, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR4222.html Sarah O. Meadows, Charles C. Engel, Rebecca L. Collins, et al., “2018 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS) Results for the Reserve Component,” rand.org, 2021, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR4228.html At the time of writing (September 2023), the most recent survey numbers are from 2018. In 2018, the most recent year for which the above data are available, 14.4% of active service members aged 20 and older were living with obesity, compared to 18.2% of the military reserve population and 42.5% of the general U.S. population. In the same year, 49.1% of active military service members aged 20 and older were overweight, compared to 47.2% of the reserves and 31.1% of the general U.S. population.

When looking at specific branches of the military, including the reserves, the Army National Guard had the highest prevalence of obesity at 20.6% of service members, followed by the Navy (19.7%) and the Navy Reserve (19.4%). The branches with the lowest percentage of service members living with obesity were the Marine Corps at 6.7% of service members, the Marine Corps Reserve (7.3%) and the Air Force Reserve (13.3%).

The Army released its first “Health of the Force” report in 2015, covering issues such as behavioral health, chronic disease, substance abuse, and obesity.US Army, “Health of the Force,” army.mil, November 2015, https://api.army.mil/e2/c/downloads/419337.pdf Using data from the previous year, the document reported that 13% of active duty Army soldiers were classified as obese in 2014, with the prevalence ranging from 9% to 18% across Army installations.US Army, “Health of the Force,” army.mil, November 2015, https://api.army.mil/e2/c/downloads/419337.pdf In the 2022 edition of “Health of the Force,” the Army reported that 20% of active service Army soldiers were classified as obese in 2021, with the prevalence ranging from 16% to 29% across bases. Defense Health Agency, “2022 Health of the Force,” Defense Centers for Public Health - Aberdeen, May 10, 2023, https://phc.amedd.army.mil/topics/campaigns/hof/Pages/default.aspx

Image: Department of Defense, “DOD Health of the Force 2021,” Military Health System, December 14, 2022, https://amarkfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/DOD-Health-of-the-Force-2021.pdf

The Army, Navy, Air Force and Defense Health Agency also release joint “Health of the Force” reports covering issues including injury, behavioral and sexual health, sleep disorders and obesity. In 2021, the overall prevalence of obesity among all active service members was 22% — a 12% increase from 2020. The report stated that "Overall obesity prevalence was higher among male (22.5%) compared to female (17.4%) and older compared to younger Service members. "Department of Defense, “DOD Health of the Force 2021,” Military Health System, December 14, 2022, https://amarkfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/DOD-Health-of-the-Force-2021.pdf In 2021, the Navy had the highest prevalence of obesity at 27%, while the Marine Corps had the lowest at 11%.Department of Defense, “DOD Health of the Force 2021,” Military Health System, December 14, 2022, https://amarkfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/DOD-Health-of-the-Force-2021.pdf

These figures underscore that the obesity epidemic impacting the general U.S. adult population increasingly affects the U.S. military. While there is a noticeable jump in obesity from the 2018 data to the numbers released in 2022, some people note concerns about how the military assesses body composition. Those are discussed in Appendix B of this report.

Cost of Obesity to the Military

Active-duty service members miss 658,000 work days each year due to issues related to being overweight or obese, costing the DoD $103 million, according to the CDC.CDC, “Unfit to Serve,” cdc.gov, June 20, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/resources/unfit-to-serve/index.html

Military leaders have been concerned about the financial impact of obesity for decades. In the 1990s, after the end of the Gulf War, the Army fired thousands of soldiers for being overweight, Ernesto Londoño, “Rising Number of Soldiers Being Dismissed for Failing Fitness Tests,” washingtonpost.com, December 10, 2012, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/2012/12/08/13d2e444-40b8-11e2-ae43-cf491b837f7b_story.html with some reports estimating that, prior to 2000, between 3,000 and 5,000 enlisted personnel were forced to leave the U.S. military annually due to exceeding weight standards. Elizabeth Cohen and Elise Zeiger, “Discharged Servicemen Dispute Military Weight Rules,” cnn.com, September 6, 2000, http://www.cnn.com/2000/HEALTH/09/06/military.obesity/index.html Between January and October 2012, the Army released 1,625 soldiers for being overweight, Ernesto Londoño, “Rising Number of Soldiers Being Dismissed for Failing Fitness Tests,” washingtonpost.com, December 10, 2012, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/2012/12/08/13d2e444-40b8-11e2-ae43-cf491b837f7b_story.html and in 2013, it was reported that an estimated 1,200 first-term military enlistees are released early each year due to weight control problems. Major General Thomas Cutler (Retired) and Major General Gerald A. Miller (Retired), “Retired Military Generals: Recruits Dismissed for Obesity Cost $1.1 Billion a Year,” mlive.com, September 29, 2013, https://www.mlive.com/news/2013/09/retired_military_generals_recr.html Similarly, a report published by the Congressional Research Service in 2020 notes that 80% of recruits who initially failed to meet height-weight standards but were subsequently allowed to serve (due to receiving a waiver or losing enough weight to fulfill the standards) left the military before completing their first term of enlistment. Congressional Research Service, “Obesity in the United States and Effects on Military Recruiting,” fas.org, December 22, 2020, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/IF11708.pdf

The estimated cost of recruiting and screening a new Army applicant is $22,000,Khaleda Rashman, “It Could Cost the Army $200 Million to Replace Soldiers Discharged for Vaccine Refusal,” newsweek.com, February 3, 2022, https://www.newsweek.com/replacing-soldiers-discharged-vaccine-refusal-cost-army-200-million-1675762 and the cost of training ranges from $55,000 to $74,000.Sean Kimmons, “OPAT Reducing Trainee Attrition, Avoiding Millions in Wasted Training Dollars, Officials Say,” army.mil, July 2, 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20230324065806/https://www.army.mil/article/207956/opat_reducing_trainee_attrition_avoiding_millions_in_wasted_training_dollars_officials_say This means that finding and replacing a discharged service member could cost between $77,000 and $96,000.

The DoD Medical Health System provides healthcare to over nine million people, including active and retired military members along with their spouses and children. The Health System is spending over $1 billion annually on obesity-related costs. Sara B. Police and Nicole Ruppert, “The US Military's Battle With Obesity,” Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, May 2022, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1499404621009532 Adding in the costs of making up for lost service member numbers, the DoD annually spends approximately $1.5 billion on replacing personnel deemed unfit as well as on obesity-related healthcare costs. CDC, “Unfit to Serve,” cdc.gov, June 20, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/resources/unfit-to-serve/index.html Soldiers who were overweight or obese had an 11% and 33% higher risk of injury, respectively. They also had a higher risk of hypertension and other cardio metabolic issues. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, “Understanding and Overcoming the Challenge of Obesity and Overweight in the Armed Forces: Proceedings of a Workshop,” National Academies Press, 2018, https://doi.org/10.17226/25128

Decreasing Recruitment due to Obesity

During an April 2023 hearing with the House Armed Services Committee, military officials testified that the Air Force, Army and Navy are all expected to fall short of their recruiting goals, again. The Army’s goal was to recruit 65,000 soldiers in 2023, but was expecting to miss that goal by 10,000.Cory Smith, “Army, Navy and Air Force Expecting to Fall Short of Recruiting Goals,” The National Desk, katv.com, April 20, 2023, https://katv.com/military-recruiting-shortfalls-army-navy-air-force-expecting-to-fall-short-of-enlistment-goals-marines-space-force-defense-armed-forces-troops-service-members The prior year, the AP reported a potential shortfall of 10,000-15,000 soldiers, which it said equated to being 18% to 25% short of its recruiting goals. Lolita C. Baldor, “Army Program Gives Poor-Performing Recruits a Second Chance,” apnews.com, August 28, 2022, https://www.usnews.com/news/politics/articles/2022-08-28/army-program-gives-poor-performing-recruits-a-second-chance

Admiral Lisa Franchetti said the Navy was expected to miss its recruitment goal by 6,000, while General David Allvin, Vice Chief of Staff, testified the Air Force was expecting a shortfall of 10,000.Cory Smith, “Army, Navy and Air Force Expecting to Fall Short of Recruiting Goals,” The National Desk, katv.com, April 20, 2023, https://katv.com/military-recruiting-shortfalls-army-navy-air-force-expecting-to-fall-short-of-enlistment-goals-marines-space-force-defense-armed-forces-troops-service-members

These numbers have a critical importance to the military recruitment goals because Congress ended the military draft in 1973. Since then, the U.S. armed forces have relied on volunteer recruits on an annual basis. A dwindling available pool for potential recruits means the U.S. military may not meet its recruitment goals. In fact, 2009 was the first time since 1973 that the Air Force, Army, Marine Corps and Navy exceeded their recruitment goals—both in terms of quantity and quality of recruits. Julie Percha, “Too Fat to Fight? Military Recruitment Grapples with Obesity Epidemic,” ABC News, abcnews.go.com, August 18, 2010, https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/military-recruitment-grapples-obesity-epidemic/story?id=11431486

Still, in the four years prior to 2009, the U.S. military had to turn away 48,000 recruits because they were overweight. That number was higher than the number of troops stationed in Afghanistan at the time. Jeffrey Levi, et al., “F as in Fat: How Obesity Policies are Failing in America,” Trust for America’s Health, 2009, https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101509792-pdf

In 2022, the U.S. Army fell 25% below its recruitment goals, and obesity constituted the largest single disqualifying factor among all military recruits for that year, amounting to 11% of those in the 17–24 age bracket. Stephen A. Cheney and Stephen N. Xenakis, “Obesity’s Increasing Threat to Military Readiness: The Challenge to U.S. National Security,” American Security Project, November 1, 2022, https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep46869?seq=2 A March 2023 report by the American Security Project, a nonprofit research organization, asserted that urgent action is required to halt (or ideally reverse) the continued shortfall; otherwise, the shortfall in recruits will “outpace the military’s replacement rate” and result in “an inability for the military to remain mission effective across all of its obligations.” American Security Project, “The Military Recruiting Crisis: Obesity’s Impact on the Shortfall,” americansecurityproject.org, March 23, 2023, https://www.americansecurityproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Ref-0281-The-Recruiting-Crisis-Obesitys-Impact.pdf

These findings are alarming because the country’s defense system is predicated on maintaining a steady number of military recruits, active-duty personnel and reservists. From 2010 to 2020, the Air Force (<-1%), Army (-14.4%) and Marine Corps (-10.7%) all experienced a decrease in recruits. Only the Navy had an increase in numbers (+5.8%), likely partly due to implementing an online recruitment system prior to COVID-19.[6] The U.S. military may be unable to carry out expected missions if current trends continue. Stephen A. Cheney and Stephen N. Xenakis, “Obesity’s Increasing Threat to Military Readiness: The Challenge to U.S. National Security,” American Security Project, November 1, 2022, https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep46869?seq=2

Evolving Body Composition Standards

The first Army weight–height standards were established in 1887, and the criteria have been revised over time to relax stringent weight-height ratio requirements. For instance, standards for World War II personnel were modified slightly from their World War I guidelines as the ideal weight increased by a rate of four pounds per inch of height. Service members were considered ill-fit for duty if their weight was “greatly out of proportion” to their height and if it interfered with, what was considered at the time, “normal physical activity or with proper training.” Karl E. Friedl, “Body Composition and Military Performance: Origins of the Army Standards,” in Bernadette M. Marriott and Judith Grumstrup-Scott (eds.), “Body Composition and Physical Performance: Applications for the Military Services,” National Academies Press, 1990, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK235960/

In 1960, U.S. Army Regulation (AR) 40-501 established new maximum weight limits according to age and gender that were deemed liberal in comparison to previous standards at the time. The upper limits for male recruits and personnel were approximately 140% of World War II recruits. Karl E. Friedl, “Body Composition and Military Performance: Origins of the Army Standards,” in Bernadette M. Marriott and Judith Grumstrup-Scott (eds.), “Body Composition and Physical Performance: Applications for the Military Services,” National Academies Press, 1990, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK235960/

In 1980, President Jimmy Carter requested an assessment of military physical fitness programs. The result was DoD Directive 1308.1, which stipulated that body fat standards would be used to assess obesity. Measuring body fat no longer relied solely on weight–height tables as had previously been done. DoD 1308.1 also established a single standard for body fat percentage. It defined obesity as possessing over 22% body fat for male personnel and over 29% for female service members. Karl E. Friedl, “Body Composition and Military Performance: Origins of the Army Standards,” in Bernadette M. Marriott and Judith Grumstrup-Scott (eds.), “Body Composition and Physical Performance: Applications for the Military Services,” National Academies Press, 1990, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK235960/

Further revisions and practices were implemented in the 1980s to address growing weight concerns among military personnel, and thus the Committee on Military Nutrition Research (CMNR) was created in October 1982 with a primary responsibility to identify contributing factors to service members’ physical and mental performance, provide diet recommendations, and oversee feeding regulations. Mary I. Poos, et al., “Committee on Military Nutrition Research: Activity Report: December 1, 1994 through May 31, 1999 > Background and Introduction,” National Academies Press, 1999, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK224682/

The military’s focus on specific guidelines for female personnel increased in the 1990s. CMNR was tasked in 1995 with reviewing military policies on fitness and body composition as part of the Defense Women’s Health Research Program. Concerns had mounted about female personnel implementing extreme practices to meet weight standards, including excessive dieting, insufficient intake of nutrients and “dangerous eating practices.” Subcommittee on Military Weight Management and Committee on Military Nutrition Research (CMNR), “Weight Management: State of the Science and Opportunities for Military Programs,” National Academies Press, 2004, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK221823/

These concerns have intensified in the 21st century. Eating disorders are particularly acute among female Marines. The Marine Corps places a significant emphasis on physical appearance in comparison with the other military branches. The Rand Corporation recommended as recently as 2022 that the Marine Corps halt its Body Composition and Military Appearance Program (BCMAP), as the Air Force recently did, while further studies are conducted. Joslyn Fleming and Jeannette Gaudry Haynie, “Inequitable Marine Corps Body Composition Policies and Their Impact on the Health of the Force,” Rand Corporation, rand.org, March 25, 2022, https://www.rand.org/blog/2022/03/inequitable-marine-corps-body-composition-policies.html

The DoD revised the 1980s Directive 1308.3 in 2002 to update weight–height standards. The new maximum BMI was 27.5 and stipulated that no military branch could have a minimum BMI of lower than 25. This revision meant that the Air Force had to decrease its standard for male personnel, while the Marine Corps had to raise its standards for female service members. The DoD also mandated that all services use a single circumferential equation for male personnel and a separate circumferential equation for female personnel when assessing percent of body fat.Subcommittee on Military Weight Management and Committee on Military Nutrition Research (CMNR), “Weight Management: State of the Science and Opportunities for Military Programs,” National Academies Press, 2004, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK221832/

The timeline below highlights major events in the history of military body composition measurements. Appendix A details the standards across military branches and some concerns about how these are conducted are discussed in Appendix B.

DoD Obesity Initiatives

Nearly 20 years ago, the Army experimented with a study, the Assessment of Recruit Motivation and Strength (ARMS), that allowed overweight recruits to obtain an enlistment waiver as long as they could pass a physical fitness test. Sheryl A. Bedno et al., “Association of Weight at Enlistment with Enrollment in the Army Weight Control Program and Subsequent Attrition in the Assessment of Recruit Motivation and Strength Study,” Military Medicine, Vol. 175, No. 3, March 2010, p. 188–193, https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-09-00288 The Army wanted to ascertain whether a relaxation in recruitment standards could result in personnel eventually being able to meet weight–height standards and not be discharged for being overweight.

The number of male recruits increased by 13% and female recruits increased by 20%. Overweight recruits, and those with too much body fat (over-body fat), constituted almost the entirety of those percentile increases. David S. Loughran and Bruce R. Orvis, “The Effect of the Assessment of Recruit Motivation and Strength (ARMS) Program on Army Accessions and Attrition,” Rand Corporation, rand.org, 2011, https://www.rand.org/pubs/periodicals/health-quarterly/issues/v1/n3/10.html Male ARMS applicants averaged 38 pounds overweight and 2.0 percentage points over-body fat, while female ARMS recruits averaged 27 pounds overweight and 2.1 percentage points over-body fat. David S. Loughran and Bruce R. Orvis, “Technical Report: The Effect of the Assessment of Recruit Motivation and Strength (ARMS) Program on Army Accessions and Attrition,” Rand Corporation, rand.org, 2011, https://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR975.html

The study found that recruits who exceeded weight–height standards but could pass the ARMS fitness test were equally capable of serving a minimum of 180 days as those who initially met standards.David S. Loughran and Bruce R. Orvis, “Technical Report: The Effect of the Assessment of Recruit Motivation and Strength (ARMS) Program on Army Accessions and Attrition,” Rand Corporation, rand.org, 2011, https://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR975.html While the ARMS study resulted in an increase in recruits, it did not improve attrition rates (defined as leaving the service in under three years of service).David S. Loughran and Bruce R. Orvis, “The Effect of the Assessment of Recruit Motivation and Strength (ARMS) Program on Army Accessions and Attrition,” Rand Corporation, rand.org, 2011, https://www.rand.org/pubs/periodicals/health-quarterly/issues/v1/n3/10.html

In 2006, the Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs established the Healthy Choices of Life initiatives. Coupled with the DoD Lifestyle Assessment Program, the aims of the initiative were to manage weight, monitor lifestyle behaviors, increase military readiness, and improve military personnel’s overall well-being. Timothy M. Dall et al., “Cost Associated with Being Overweight and with Obesity, High Alcohol Consumption, and Tobacco use Within the Military Health System’s TRICARE Prime-Enrolled Population,” American Journal of Health Promotion, Vol. 22, No. 2, November/December 2007, p. 120–139, https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-22.2.120

Some military branches have implemented prep courses, or delayed entry courses, to offer overweight recruits an opportunity to meet standards in an effort to increase recruitment numbers.

The Marine Corps runs a delayed entry program that allows recruits to postpone recruit training for up to 410 days. While not solely designed to give overweight recruits time to get in shape (the program also allows time for the graduation of high school or college, for example), the program does provide a mentoring system that includes a strict physical regimen with periodic testing to manage weight and prepare recruits physically and mentally for basic training. The Marines, “Physical Fitness,” marines.com, accessed July 17, 2023, https://www.marines.com/life-as-a-marine/standards/physical-fitness.htmlThe Marines “Delayed Entry Program,” marines.com, accessed July 17, 2023, https://www.marines.com/become-a-marine/process-to-join/delayed-entry-program.html

Army recruits are generally allowed to go to basic training if they are up to 2% over the body fat limit because people tend to get in better shape during training. A new Army prep course gives recruits who are between 2% and 6% over the body fat limit up to 90 days of fitness instruction to help them get in better shape, with the goal of getting people qualified for service who would otherwise be rejected based on body fat.Lolita C. Baldor, “Basic Training Without Yelling: Army Recruits Get 2nd Chance,” kgw.com, March 29, 2023, https://www.kgw.com/article/news/nation-world/basic-training-without-yelling-army-recruits-get-2nd-chance/507-884a3ef2-2d16-4597-b404-bdcb6d12b297Lolita C. Baldor, “Army Program Gives Poor-Performing Recruits a Second Chance,” apnews.com, August 28, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/army-government-and-politics-b83a930a681bebbe367779ecdd48c662

The Army’s Future Soldier Preparatory Course pilot program began at Fort Jackson in August 2022;U.S. Army Public Affairs, “Army Announces Creation of Future Soldier Preparatory Course,” army.mil, July 26, 2022, https://www.army.mil/article/258758/army_announces_creation_of_future_soldier_preparatory_course within eight months, 1,400 recruits had passed the fitness program and participants lost an average of 4–6% of their body fat. Recruits in the prep course are tested weekly, and they are forced to leave if they do not meet standards at the end of the 90 days. The attrition rate for recruits coming into basic and advanced individual training from the prep course was similar to that of new recruits who did not need the prep course to qualify, about 6%.Lolita C. Baldor, “Basic Training Without Yelling: Army Recruits Get 2nd Chance,” kgw.com, March 29, 2023, https://www.kgw.com/article/news/nation-world/basic-training-without-yelling-army-recruits-get-2nd-chance/507-884a3ef2-2d16-4597-b404-bdcb6d12b297

The initiative’s success prompted the Navy to implement a similar class. Starting in April 2023 with an initial intake of 60 to 80 recruits who were 6% above the Navy’s body composition requirements, the three-week fitness class (that can be repeated for up to 90 days), is designed to bring the recruits up to the standard needed to join the Navy boot camp. The Air Force has made note of these programs, but has announced that it is currently focusing on other ways to boost its recruitment numbers. Lolita C. Baldor, “Basic Training Without Yelling: Army Recruits Get 2nd Chance,” kgw.com, March 29, 2023, https://www.kgw.com/article/news/nation-world/basic-training-without-yelling-army-recruits-get-2nd-chance/507-884a3ef2-2d16-4597-b404-bdcb6d12b297

In response to concerns about service members’ fitness, military bases have cut back on fried foods and sugary drinks, expanded gym hours and increased unit workouts. Changes in the military base dining halls included color-coding foods with green labels for healthy foods and red labels for junk food. More nutritional snacks were offered, and lower fat options such as salads were more prominently displayed. Dave Philipps, “Trouble for the Pentagon: The Troops Keep Packing On the Pounds,” nytimes.com, September 4, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/04/us/military-obesity.html Even still, the problem continues to grow.

Conclusion

The obesity epidemic is an undeniable concern—not just for the general U.S. adult population but also for the U.S. military. The DoD has implemented several programs in an effort to address a diminishment in the viable recruitment pool due to excessive weight, some of which have increased recruit numbers but not attrition rates.

Body composition standards have also changed across military branches over the years, however concerns still linger about the accuracy of these requirements (as outlined in Appendix B).

The DoD could address both the obesity epidemic and lingering inaccuracies in several ways. The Army and Navy have already implemented one method: they developed a course for potential recruits to work towards meeting weight standards before enlisting rather than rejecting them outright. It remains to be seen how effective this method will be in garnering more recruits and offsetting the national security crisis.

Another method would be to differentiate the body composition standards in accordance with particular military roles. Some positions, by their very nature, are more sedentary, such as drone operators. Stipulating that all service members meet the same weight standards regardless of their military duties could be considered counterintuitive.

The DoD could also relax the current weight standards while maintaining other requirements regarding muscle strength, cardiovascular fitness and nutrition. This idea is based on the ARMS study, which found that some service members with a higher BMI perform well in combat roles requiring strength, particularly women.

Editor’s Note: Efforts were made to obtain more specific statistics about obesity in the U.S. military going back 40 years. We contacted records officers within the Army Records Management Directorate, U.S. Marine Corps Records Office, the National Guard Bureau Records Office, the Air Force and Space Force Records Office, and the Navy Records Office, along with the Chief Information Officer of the DoD. Most requests were left unanswered. The Air Force and Space Force Records Officer, however, sent contact information for the Air Force Medical Readiness Agency and Surgeon General. These latter entities responded to inquiries, but the requested information has not yet been received. We also filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. The Defense Health Agency FOIA Records Officer responded to follow-ups about the request, but the records search had not been completed at the time of this report's publication.

Appendix A: Body Composition Standards Across Military Branches

Marines

In 1980, the Marine Corps added a body fat standard to its body composition regulations. Male service members could not exceed 26% body fat and female personnel could not exceed 36%.Jeannette Haynie et al., “Impacts of Marine Corps Body Composition and Military Appearance Program (BCMAP) Standards on Individual Outcomes and Talent Management,” Rand Corporation, rand.org, 2022, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA1100/RRA1189-1/RAND_RRA1189-1.pdf The Marine Corps’ separate body composition policies underscore that the DoD’s single standard was more of a guideline than strict regulation. Each military branch could still develop its own standards.

Body composition standards implemented by the Marine Corps on January 1, 2023, assess service members according to BMI and body circumference. Male service members are measured at the waist and neck; female personnel are measured at the waist, neck and hips.US Marine Corps Human Performance Branch, “Body Composition Program Standards,” marines.mil, February 23, 2021, https://www.fitness.marines.mil/BCP_Standards/ If personnel receive a score of 285 or higher on their physical fitness test and combat fitness test, they are exempt from body fat standards. People who score between 250 and 284 on their physical and combat fitness tests receive an extra 1% body fat allowance. Marine Corps, “Marine Corps Body Composition Worksheet,” marines.mil, accessed July 12, 2023, https://www.fitness.marines.mil/Portals/211/documents/Height%20and%20Weight%20Worksheet.pdf Marines are required to pass the physical fitness test once a year.Marines.com, “Physical Requirements,” marines.com, accessed July 13, 2023, https://www.marines.com/become-a-marine/requirements/physical-fitness.html

Army

Body composition standards implemented by the Army in June 2023 assess service members according to BMI and body circumference. If soldiers exceed the maximum weight for height BMI calculation, then they must be tested for percentage body fat using the body circumference measure. Both male and female service members are measured at the waist only.Army Publishing Directive, “ALARACT 046/2023 - Notification of New Army Body Fat Assessment for the Army Body Composition Program,” armypubs.army.mil, June 2023, https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN38537-ALARACT_0462023-000-WEB-1.pdf

Like the Marine Corps, the Army has also implemented exemptions for its service members. Soldiers who score 540 or higher on the Army Combat Fitness Test (ACFT) are exempt from body fat assessment, as long as they have scored a minimum of 80 points on each of the six elements of the test. Those who do not receive high scores are measured according to BMI and body circumference. Secretary of the Army, “Army Directive 2023-08,” army.mil, March 15, 2023, https://www.armyresilience.army.mil/abcp/pdf/AD%202023-08-Army%20Body%20Composition%20Exemption%20for%20ACFT%20Score.pdf Soldiers are required to take the ACFT twice a year. Secretary of the Army, Washington, “Memorandum for SEE Distribution, Subject: Army Directive 2022-05 (Army Combat Fitness Test),” armypubs.army.mil, March 23, 2022, https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN35052-ARMY_DIR_2022-05-000-WEB-1.pdf

Navy

The Navy has a three-part assessment procedure for its body composition standards. Service members are first tested according to BMI. If they exceed BMI standards, their abdominal circumference is then measured. Service members who again exceed requirements (39 inches for men and 35.5 inches for women) must then undergo body circumference measurement to gauge percentage body fat. Similar to Marine Corps standards, male service members are measured at the waist and neck, while female service members are measured at the waist, neck and hips.Navy Physical Readiness Program, “Guide 4: Body Composition Assessment (BCA),” navy.mil, January 2023, https://www.mynavyhr.navy.mil/Portals/55/Support/Culture%20Resilience/Physical/Guide_4-Body_Composition_Assessment_BCA_JAN_2023.pdf?ver=V-3wCu5X586wXMTCa4C2ag%3D%3D Service members are tested once or twice a year.U.S. Department of the Navy, “OPNAV Instruction 6110.1K,” secnav.navy.mil, April 22, 2022 https://www.secnav.navy.mil/doni/Directives/06000%20Medical%20and%20Dental%20Services/06-100%20General%20Physical%20Fitness/6110.1K.pdf#search=obesity

In April 2022, the Navy released a new directive regarding its physical readiness program. The Navy stipulated that all active-duty and reserve personnel would need to adhere to strict standards regarding abdominal circumference measurements, nutrition, cardiorespiratory fitness, strength training, neuromuscular exercise and flexibility. The directive is subject to yearly review and is to remain in effect until 2032 unless revised or canceled prior to that date. U.S. Department of the Navy, “OPNAV Instruction 6110.1K,” secnav.navy.mil, April 22, 2022 https://www.secnav.navy.mil/doni/Directives/06000%20Medical%20and%20Dental%20Services/06-100%20General%20Physical%20Fitness/6110.1K.pdf#search=obesity The Navy is, therefore, expanding its focus on weight standards in an effort to perform more holistic assessments of its service members.

Coast Guard

The Coast Guard has a similar assessment procedure to that of the Navy. Service members are first screened according to BMI. Personnel who exceed BMI standards in accordance with their weight–height ratio must then undergo a body fat assessment and abdominal circumference measurement. For the body fat assessment, men are measured at the waist and neck, while women are measured at the waist, neck and buttocks.

While other branches of the military have different height-weight standards for male and female service members, the Coast Guard’s height-weight standards are gender neutral. Service members must undergo a body composition screening twice a year and boat crew members must also pass a semi-annual physical fitness test.United States Coast Guard, “Body Composition Standards Program,” defense.gov, March 2022, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Mar/31/2002967299/-1/-1/0/CI_1020_8I.PDF United States Coast Guard, “Section D. Physical Fitness Standards,” dcms.udcg.mil, 2019, https://www.dcms.uscg.mil/Portals/10/CG-1/cg133/pdf/Boat_Crew_Fitness_Test.pdf?ver=2019-08-01-083908-503

Air Force and Space Force

The Air Force’s and the U.S. Space Force’s (USSF) Body Composition Programs (BCP), implemented in April 2023, assess physical readiness based on waist-to-height ratios. Abdominal circumference is measured and then divided by the personnel’s height in inches. The new standard requires service members to have a waist-to-height ratio of less than 0.55. Body Composition Assessments are undertaken annually. Personnel who do not meet the required standards must enroll in a Body Composition Improvement Program for a year.Air Force, “Body Composition Program Policy Memo,” af.mil, January 5, 2023, https://www.af.mil/Portals/1/documents/2023SAF/Tab_1._Air_Force_Body_Composition_Policy_Memo.pdf Air Force, “United States Space Force Body Composition Program,” af.mil, January 13, 2023, https://www.af.mil/Portals/1/documents/2023SAF/USSF_Body_Composition_Program_Memo_JAN2023.pdf

Separate from the Body Composition Assessment is the Air and Space Force’s Physical Fitness Assessment in which service members are tested on their cardiovascular, core endurance and muscular strength. Personnel who pass with an excellent grade repeat the assessment every 12 months. Those who pass satisfactorily repeat the assessment every 6 months and those who are graded unsatisfactory have to retake the assessment within 3 months. Secretary of the Air Force, “Department of the Air Force Manual 36-2905,” afpc af.mil, April 21, 2022, https://www.afpc.af.mil/Portals/70/documents/FITNESS/dafman36-2905.pdf

Appendix B. Problems with How the Military Assesses Body Composition

While obesity in the military is still a problem in need of a solution, some people have raised concerns with how the military assesses the body composition of service members. The sections below offer more information.

Lack of Medical Expertise

Assessments are not always conducted by qualified medical professionals trained in “accession medicine,” Defined as “evaluating the suitability of the moral, physical, and mental condition of prospective applicants for entry into military service.” See: Maria C. Lytell, et al.., “Improving US Military Accession Medical Screening Systems,” rand.org, 2019, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2780.html creating the potential for inaccurate results. A report from Rand Corporation recommended that medical experts trained by the U.S. Military Entrance Processing Command should be used at all levels of the screening process in order to rule out potential bias and ensure accurate consistency in fitness assessments.Maria C. Lytell, et al.., “Improving US Military Accession Medical Screening Systems,” rand.org, 2019, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2780.html

Inaccuracy of BMI

BMI does not diagnose body fat, nor does it account for the location of fat distribution in the body. A reliance on BMI equations for assessment purposes, therefore, constitutes another concern. The CDC has stressed that other methods must be used to measure body fat percentage. Genetics and sex both play a role in the amount and distribution of body fat. The CDC states that women tend to carry more body fat than men, and older individuals often have more body fat than younger people. CDC, “Mean Percentage Body Fat by Age Group and Sex — National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 1999-2004,” cdc.gov, 2008, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5751a4.htm

A 2022 Rand report focusing on the Air Force attempted to address these aforementioned concerns. It found that if only BMI was used, it would appear that airmen have been increasingly unfit for the past decade. However, when implementing other measurements such as cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular strength and abdominal circumference, airmen’s fitness has improved. The average 1.5-mile run times have decreased, and the number of sit-ups and push-ups airmen can complete during fitness tests has increased. The difference in measuring physical fitness among Air Force personnel based on the assessment method is staggering. According to just BMI, 60% of airmen would be classified as overweight or obese. When measuring waist–height standards, only 14–22% of airmen exceed requirements. Abdominal circumference standards demonstrated that less than 1% of airmen exceed thresholds. Sean Robson et al., “Is Today’s U.S. Air Force Fit? It Depends on How Fitness is Measured,” Rand Corporation, dtic.mil, 2022, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1167763.pdf How fitness and physical capabilities are measured, therefore, results in vastly different findings.

Gender Disparities

Although the aforementioned statistics have indicated that the DoD has one weight–height standard for male personnel and another for female service members, revisions for the two sexes have not been comparable. For instance, the three dozen changes to AR 40-501 implemented between 1960 and 1983 resulted in decreasing the maximum allowable weight for women by 15–20 pounds. Such revisions were more restrictive than for their male counterparts. Karl E. Friedl, “Body Composition and Military Performance: Origins of the Army Standards,” in Bernadette M. Marriott and Judith Grumstrup-Scott (eds.), “Body Composition and Physical Performance: Applications for the Military Services,” National Academies Press, 1990, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK235960/ A 1963 Marine Corps pamphlet entitled “Slim and Trim: For Women Marines” stressed that female Marines “must always be the smallest group of women in the military service. In accordance with the Commandant’s desire, they must also be the most attractive and useful women in the four line services.”Jeannette Haynie et al., “Impacts of Marine Corps Body Composition and Military Appearance Program (BCMAP) Standards on Individual Outcomes and Talent Management,” Rand Corporation, rand.org, 2022, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA1100/RRA1189-1/RAND_RRA1189-1.pdf

This double standard has continued into the twenty-first century. It most likely contributes to the higher percentage of female military personnel—particularly among Marines—who undergo extreme measures to meet standards. Joslyn Fleming and Jeannette Gaudry Haynie, “Inequitable Marine Corps Body Composition Policies and Their Impact on the Health of the Force,” Rand Corporation, rand.org, March 25, 2022, https://www.rand.org/blog/2022/03/inequitable-marine-corps-body-composition-policies.html Despite the fact that female Marines are diagnosed with more eating disorders than any other group within the DoD, Joslyn Fleming and Jeannette Gaudry Haynie, “Inequitable Marine Corps Body Composition Policies and Their Impact on the Health of the Force,” Rand Corporation, rand.org, March 25, 2022, https://www.rand.org/blog/2022/03/inequitable-marine-corps-body-composition-policies.html of the four branches of the military that measure using BMI, the Army has the most restrictive measures in place for females and the Coast Guard has the least restrictive standards.US Marine Corps Human Performance Branch, “Body Composition Program Standards,” marines.mil, February 23, 2021, https://www.fitness.marines.mil/BCP_Standards/Army Publishing Directive, “ALARACT 046/2023 - Notification of New Army Body Fat Assessment for the Army Body Composition Program,” armypubs.army.mil, June 2023, https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN38537-ALARACT_0462023-000-WEB-1.pdf Navy Physical Readiness Program, “Guide 4: Body Composition Assessment (BCA),” navy.mil, January 2023, https://www.mynavyhr.navy.mil/Portals/55/Support/Culture%20Resilience/Physical/Guide_4-Body_Composition_Assessment_BCA_JAN_2023.pdf?ver=V-3wCu5X586wXMTCa4C2ag%3D%3D United States Coast Guard, “Body Composition Standards Program,” defense.gov, March 2022, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Mar/31/2002967299/-1/-1/0/CI_1020_8I.PDF

There are added complications to relying on BMI as an accurate assessment of physical fitness for women. A 2020 study of 362 female soldiers (133 Army trainees and 229 active-duty soldiers) found that those with a higher BMI tended to outperform those with a lower BMI in common soldiering tasks (CSTs).Jan E. Redmon et al., “Relationship of Anthropometric Measures on Female Trainees’ and Active Duty Soldiers’ Performance of Common Soldiering Tasks,” Military Medicine, Vol. 185, January/February 2020, p. 376–382, https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usz319 The findings were in accord with a 2017 study that determined female soldiers with increased BMI had better performance on fitness tests requiring muscular power and strength. Joseph R. Pierce et al., “Body Mass Index Predicts Selected Physical Fitness Attributes but is not Associated with Performance on Military Relevant Tasks in U.S. Army Soldiers,” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 2017, p.S79–S84, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2017.08.021 Restrictive female BMI standards could consequently result in the rejection of soldiers who might perform combat-related tasks efficiently.

Weight Categorization Challenges

Another concern relates to miscategorizing service members’ perceived excess weight as body fat rather than muscle mass. The DoD has recognized the potential inaccuracy of categorizing muscular personnel as overweight. The 2015 HRBS stated that “very muscular individuals may be incorrectly classified as unhealthy based on standard BMI cutoffs.” Because “muscle mass can contribute to a heavier weight, it is not clear whether all service members categorized as overweight were actually unhealthy.” DoD, “2015 Health Related Behaviors Survey: Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Among U.S. Active-Duty Service Members,” Rand Corporation, rand.org, 2015, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1695.html The same study also asserted that the implementation of a systemic tracking better accounting for muscle mass—such as during physical exams or fitness tests—might give more accurate assessments of military personnel who are overweight and/or obese due solely to body fat percentage rather than increased muscle mass. DoD, “2015 Health Related Behaviors Survey: Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Among U.S. Active-Duty Service Members,” Rand Corporation, rand.org, 2015, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1695.html

Weight Standards Customized to Duties

Stringent requirements do not account for illness or for specific military duties. Soldier Paul Crane, for example, was discharged from the Army after 15 years of service for being eight pounds overweight. He claimed that he was required to weigh in while recovering from a knee surgery that precluded his ability to exercise and he was weighed in with his crutches and bandages. Crane sued and won his case; he has since been reinstated. Elizabeth Cohen and Elise Zeiger, “Discharged Servicemen Dispute Military Weight Rules,” cnn.com, September 6, 2000, https://www.cnn.com/2000/HEALTH/09/06/military.obesity/index.html#:~:text=(CNN%20NewsStand)%20%2D%2D%20Paul%20Crane,for%20being%208%20pounds%20overweight

Sailor Bill Torrance was similarly discharged due to “weight control failure” in 1997. He was found to be 10 pounds overweight, yet only exceeded the body fat standard by 1%. The Navy also demanded that he pay back his reenlistment bonus. Both Crane and Torrance argued that had the military relied on $35 calipers, their body composition assessments would have been more accurate and not resulted in their discharges. CNN, “Discharged Servicemen Dispute Military Weight Rules,” cnn.com, September 6, 2000, http://www.cnn.com/2000/HEALTH/09/06/military.obesity/index.html Torrance further argued that his discharge did not account for his specific military duties: “My job was to sit in front of a sonar screen for six hours a day.” Justin Brown, “How Far Can Military Go in Punishing Obese Soldiers,” csmonitor.com, November 9, 2000, https://www.csmonitor.com/2000/1109/p6s2.html

Current military standards do not make distinctions between military roles. Personnel assigned to cybersecurity, drones, sonar and other similar duties dictate a more sedentary active-duty role than other service members. This poses an interesting question: is it more equitable to have the same standards within each military branch or should there be differentiated requirements in accordance with particular duties? The DoD has not announced any plans to make distinctions for personnel assigned to different tasks.

COVID-19 Impact

The COVID-19 pandemic has complicated the DoD’s anti-obesity efforts. Tracey Koehlmoos, PhD, Director of the Center for Health Services Research at the Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, Maryland, co-conducted a study of all active-duty Army soldiers from February 2019 to June 2021. She found that 26.7% of soldiers who had a healthy BMI prior to the pandemic became overweight during COVID-19, and 15.6% of overweight active-duty soldiers became obese. That amounts to nearly 10,000 active-duty Army personnel developing obesity—a 5% growth in just two years. Marc Wuerdeman, Amanda Banaag and Tracey Koehlmoos,, “A Cohort Study of BMI Changes Among US Army Soldiers During the COVID-19 Pandemic in 2020-2021,” Obesity, Volume 30, Issue S1, Oral Abstracts, November 2022, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/oby.23625

A report published by the Military Health System and Defense Health Agency in January 2023 found overweight and obesity rates of active-duty personnel had increased across the Army, Marine Corps, Navy and Air Force during the pandemic. The prevalence of obesity increased from 16.6% in 2020 to 18.8% in 2021. When both obese and overweight personnel were considered, the prevalence of unfit service members increased from 65.2% in 2020 to 67.3% in 2021. That amounts to a 3.2% increase of overweight and obese military personnel within the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Military Health System, “Increased Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity and Incidence of Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” health.mil, January 1, 2023, https://health.mil/News/Articles/2023/01/01/Diabetes-During-COVID19 The U.S. military asserts that early pandemic lockdowns, such as gym closures, account for at least some of that percentage increase. Jonel Aleccia, “‘The Uniform was Tighter’: Almost a Quarter of the U.S. Military Became Obese During the Pandemic,” Fortune, fortune.com, April 2, 2023, https://fortune.com/well/2023/04/02/us-military-obesity-army-navy-marines-nearly-25-percent-increase/