Executive Summary

Opioids are powerful pain-relieving chemicals that can also produce feelings of euphoria, making them prone to misuse and addiction. In the late 1990s, the number of prescriptions for opioid medications, particularly OxyContin, skyrocketed and a wave of fatal overdoses quickly followed. In 2010, a second wave of the opioid crisis emerged, driven by fatal overdoses involving heroin, a natural opioid with pain-relieving and euphoria-inducing effects similar to OxyContin. In 2013, illicit drug manufacturers began mixing synthetic opioids such as fentanyl into heroin, cocaine, counterfeit pills, and other illegal drugs. With a potency 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine, fentanyl has propelled the most lethal wave of the United States’ ongoing opioid crisis. By 2021, opioids were involved in 80,411 overdose deaths (75.4% of all overdose deaths recorded), 88% of which specifically involved synthetic opioids.

Geographically, Northeast and Appalachian states have been at the epicenter of the crisis, but fentanyl-related deaths have sharply risen on the West Coast since 2016. In California, for example, fatal overdoses involving fentanyl rose from 1,603 deaths in 2019 to 6,095 in 2022.California Overdose Surveillance Dashboard, “California Dashboard,” skylab.cdph.ca.gov, accessed November 6, 2023, https://skylab.cdph.ca.gov/ODdash/?tab=CA

The pace has been particularly alarming in Los Angeles (LA) County, where fentanyl overdose deaths increased 1,280% from 2016 to 2021. Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, “Data Report: Fentanyl Overdoses in Los Angeles County,” publichealth.lacounty.gov, October 2023 (updated), http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/sapc/MDU/SpecialReport/FentanylOverdosesInLosAngelesCounty.pdf

The fentanyl epidemic impacts all demographic and socioeconomic groups, but its effects are not distributed evenly. Fentanyl-related deaths are disproportionately high among men, who accounted for 73% of fatal fentanyl overdoses in 2020, and mortality rates are also high among low-income communities and people experiencing homelessness. Julie O’Donnell, et al., “Trends in and Characteristics of Drug Overdose Deaths Involving Illicitly Manufactured Fentanyls – United States, 2019-2020,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 70, No. 50, p. 1740-1746, December 17, 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/pdfs/mm7050e3-H.pdf

In LA County, an estimated 75,518 people experience homelessness on any given night, and the unhoused population has been hit especially hard by the fentanyl epidemic. Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, “LA’s Homeless Response Leaders Unite to Address Unsheltered Homelessness as Homeless Count Rises,” lahsa.org, June 29, 2023, https://www.lahsa.org/news?article=927-lahsa-releases-results-of-2023-greater-los-angeles-homeless-count In 2020 and 2021, more people experiencing homelessness died from a drug overdose than in the six previous years combined, according to the LA County Department of Health. Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, “Mortality Rates and Causes of Death Among People Experiencing Homelessness in Los Angeles County 2014-2021,” publichealth.lacounty.gov, May 2023, http://www.publichealth.lacounty.gov/chie/reports/Homeless_Mortality_Report_2023.pdf In Skid Row, a downtown Los Angeles neighborhood known as the center of the city’s homelessness crisis, fentanyl fueled an eleven-fold increase in fatal overdoses from 2017 to 2022. Clara Harter, “Fentanyl Drives Spike in Skid Row Overdose Deaths, 148 Recorded in 2022,” dailynews.com, August 31, 2023,https://www.dailynews.com/2023/08/31/fentanyl-drives-spike-in-skid-row-overdose-deaths-248-recorded-in-2022/

Local and federal leaders have scrambled to slow the crisis as fentanyl continues claiming lives at a shocking pace. One of the most promising short-term strategies involves distributing testing strips that can detect fentanyl in drug samples, and Narcan, a naloxone nasal spray that can reverse an opioid overdose. Nadia Kounang, “Naloxone Reverses 93% Of Overdoses, but Many Recipients Don’t Survive a Year,” cnn.com, October 30, 2017, https://www.cnn.com/2017/10/30/health/naloxone-reversal-success-study/index.html

In recent years, states like California have established initiatives to distribute naloxone and test strips in hopes of preventing overdose deaths, and the Biden Administration has called for increasing state-federal collaboration to support these programs. California MAT Expansion Project, “Naloxone Distribution Project,” californiamat.org, accessed September 26, 2023, https://californiamat.org/matproject/naloxone-distribution-project/ The White House, “Fact Sheet: White House Releases 2022 National Drug Control Strategy that Outlines Comprehensive Path Forward to Address Addiction and the Overdose Epidemic,” whitehouse.gov, April 21, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/04/21/fact-sheet-white-house-releases-2022-national-drug-control-strategy-that-outlines-comprehensive-path-forward-to-address-addiction-and-the-overdose-epidemic/ Simultaneously, state and federal efforts are underway to disrupt fentanyl distribution networks by cracking down on criminal financial networks, seizing fentanyl from traffickers trying to smuggle drugs into the United States, and imposing harsher criminal penalties on drug dealers. The White House, “Fact Sheet: White House Releases 2022 National Drug Control Strategy that Outlines Comprehensive Path Forward to Address Addiction and the Overdose Epidemic,” whitehouse.gov, April 21, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/04/21/fact-sheet-white-house-releases-2022-national-drug-control-strategy-that-outlines-comprehensive-path-forward-to-address-addiction-and-the-overdose-epidemic/

While it’s too early to tell how successful these measures will be, state and federal leaders clearly view the fentanyl epidemic as an urgent national crisis. In March 2023, the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security described fentanyl as “the single greatest challenge we face as a country.” Nick Miroff, “Fentanyl Is ‘Single Greatest Challenge’ US Faces, DHS Secretary Says,” washingtonpost.com, March 29, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2023/03/29/fentanyl-mayorkas-threat-dhs/ As opioid overdoses kill more than 1,500 people in the U.S. each week, this report aims to understand the causes of the fentanyl epidemic and its impact on people experiencing homelessness, the conditions that have made it so lethal, and whether government measures to contain the crisis will be enough. Claire Klobucista and Alejandra Martinez, “Fentanyl and the US Opioid Epidemic,” cfr.org, last updated April 19, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/fentanyl-and-us-opioid-epidemic

The Opioid Crisis in Three Waves

Opioids are powerful pain-relieving chemicals that can also produce feelings of euphoria, making them addictive. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Commonly Used Terms,” cdc.gov, accessed September 6, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/opioids/basics/terms.html This class of chemicals includes natural opioids like heroin as well as prescription opioids, such as oxycodone and morphine. High rates of misuse and addiction throughout the twentieth century prompted significant regulations on prescription opioids, and for decades, physicians rarely prescribed opioids except to manage severe pain related to cancer, palliative care, and surgery. Teresa Rummans, M. Caroline Burton, and Nancy L. Dawson, “How Good Intentions Contributed to Bad Outcomes: The Opioid Crisis,” Mayo Clinic Proceedings, Vol. 93, Issue 3, March 2018, p. 344-350, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.12.020 Keith Humphreys, et al., “Responding to the Opioid Crisis in North America and Beyond: Recommendations of the Stanford-Lancet Commission,” Vol. 399, Issue 10324, February 5, 2022, p. 555-604, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02252-2

The First Wave

After the Food and Drug Administration approved OxyContin in 1995, fatal overdoses involving prescription opioids began climbing.Keith Humphreys, et al., “Responding to the Opioid Crisis in North America and Beyond: Recommendations of the Stanford-Lancet Commission,” Vol. 399, Issue 10324, February 5, 2022, p. 555-604, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02252-2 OxyContin is an opioid medication that releases pain-relieving and euphoria-inducing chemicals over an extended period. Keith Humphreys, et al., “Responding to the Opioid Crisis in North America and Beyond: Recommendations of the Stanford-Lancet Commission,” Vol. 399, Issue 10324, February 5, 2022, p. 555-604, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02252-2 The drug’s manufacturer, Purdue Pharma, touted the extended-release formulation to aggressively and fraudulently promote OxyContin as less addictive than other opioids, claiming it was safe for treating a broad range of conditions. Keith Humphreys, et al., “Responding to the Opioid Crisis in North America and Beyond: Recommendations of the Stanford-Lancet Commission,” Vol. 399, Issue 10324, February 5, 2022, p. 555-604, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02252-2 Art Van Zee, “The Promotion and Marketing of OxyContin: Commercial Triumph, Public Health Tragedy,” American Journal of Public Health, Volume 99, Issue 2, February 2009, p. 221-227

From 1997 to 2005, physicians increasingly prescribed opioids, particularly OxyContin, to treat common issues such as headaches and sprained ankles, and opioid prescriptions grew 533%.Sarah G. Mars, et al., “‘Every ‘Never’ I Ever Said Came True:’ Transitions from Opioid Pills to Heroin Injecting,” International Journal of Drug Policy, Volume 25, Issue 2, October 19, 2013, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3961517/Patrick Radden O’Keefe, “The Family That Built an Empire of Pain,” newyorker.com, October 30, 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/10/30/the-family-that-built-an-empire-of-painKeith Humphreys, et al., “Responding to the Opioid Crisis in North America and Beyond: Recommendations of the Stanford-Lancet Commission,” Vol. 399, Issue 10324, February 5, 2022, p. 555-604, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02252-2 Highly potent opioids quickly became widely accessible, including to those without a prescription, and nonmedical opioid use, opioid addiction, and fatal overdoses skyrocketed.Teresa Rummans, M. Caroline Burton, and Nancy L. Dawson, “How Good Intentions Contributed to Bad Outcomes: The Opioid Crisis,” Mayo Clinic Proceedings, Vol. 93, Issue 3, March 2018, p. 344-350, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.12.020 The crisis was primarily concentrated in the Northeast and Appalachia, Sarah G. Mars, et al., “‘Every ‘Never’ I Ever Said Came True:’ Transitions from Opioid Pills to Heroin Injecting,” International Journal of Drug Policy, Volume 25, Issue 2, October 19, 2013, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3961517/ but emergency department visits related to prescription opioids soared nationwide, Mark Jones, Omar Viswanath, Jacquelin Peck, Alan D. Kaye, Jatinder S. Gill, and Thomas T. Simopoulos, “A Brief History of the Opioid Epidemic and Strategies for Pain Medicine,” Pain and Therapy, Vol. 7, 2018, p. 13-21, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-018-0097-6 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), “Emergency Visits for Opioid Use Rose While Treatment for Illicit Drug Use Remained Unchanged,” AHRQ Publication No. 21-0052, ahrq.gov, August 2021, https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/research/findings/nhqrdr/qdr-data-spotlight-opioids-edvisits-tx.pdf and from 2000 to 2014, rates of prescription opioid-related deaths grew from 1.5 to 5.9 deaths per 100,000 population. Wilson M. Compton, et al., “Relationship Between Nonmedical Prescription-Opioid Use and Heroin Use,” The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 374, January 14, 2016, p. 154-163, https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmra1508490

The Second Wave

As prescription opioid addiction took hold in the U.S., heroin was becoming increasingly available, pure, and cheap.Wilson M. Compton, et al., “Relationship Between Nonmedical Prescription-Opioid Use and Heroin Use,” The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 374, January 14, 2016, p. 154-163, https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmra1508490 Heroin is a natural opioid that produces similar effects to prescription opioids like OxyContin. Rates of heroin use started growing across all groups nationwide around 2007, but the opioid crisis presented a unique opportunity for traffickers to expand heroin markets to cities and small towns where they had previously not worked, drawing in opioid users with heroin’s “comparatively low price.” Keith Humphreys, et al., “Responding to the Opioid Crisis in North America and Beyond: Recommendations of the Stanford-Lancet Commission,” Vol. 399, Issue 10324, February 5, 2022, p. 555-604, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02252-2

Fatal heroin overdoses surged from 3,036 deaths in 2010 to 10,574 in 2014, marking the onset of a second wave of the opioid crisis. United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), “Unclassified: National Heroin Threat Assessment Summary – Updated,” DEA-DCT-DIR-031-16, dea.gov, June 2016, https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2018-07/hq062716_attach.pdf Already high mortality rates in Appalachia and the Northeast grew higher, but the wave of heroin overdose deaths hit urban areas especially hard, Keith Humphreys, et al., “Responding to the Opioid Crisis in North America and Beyond: Recommendations of the Stanford-Lancet Commission,” Vol. 399, Issue 10324, February 5, 2022, p. 555-604, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02252-2 disproportionately impacting Black men and those aged 20 to 34. Sarah G. Mars, et al., “‘Every ‘Never’ I Ever Said Came True:’ Transitions from Opioid Pills to Heroin Injecting,” International Journal of Drug Policy, Volume 25, Issue 2, October 19, 2013, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3961517/

The Third Wave

Around 2013, the opioid crisis evolved again as illicit drug makers began mixing synthetic opioids into counterfeit pills, heroin, and other drugs. Keith Humphreys, et al., “Responding to the Opioid Crisis in North America and Beyond: Recommendations of the Stanford-Lancet Commission,” Vol. 399, Issue 10324, February 5, 2022, p. 555-604, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02252-2 Matthew Gladden, Pedro Martinez, and Puja Seth, “Fentanyl Law Enforcement Submissions and Increases in Synthetic Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths – 27 States, 2013-2014,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 65, No. 33, August 26, 2016, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/pdfs/mm6533a2.pdf From 2014 to 2015, the number of drugs that tested positive for fentanyl in law enforcement labs more than doubled, from 5,343 positive samples to 13,882. Matthew Gladden, Pedro Martinez, and Puja Seth, “Fentanyl Law Enforcement Submissions and Increases in Synthetic Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths – 27 States, 2013-2014,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 65, No. 33, August 26, 2016, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/pdfs/mm6533a2.pdf

Synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, are created in laboratories and replicate the effects of natural opioids with greater potency. United States Drug Enforcement Administration, “Synthetic Opioids,” dea.gov, accessed September 6, 2023, https://www.dea.gov/factsheets/synthetic-opioids Fentanyl can be up to 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine, and it can be a valuable prescription drug in clinical settings as an anesthetic or for patients with extreme pain. alifornia Department of Public Health, “The Facts About Fentanyl,” cdph.ca.gov, last updated September 25, 2023, https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CCDPHP/sapb/Pages/Fentanyl.aspx# Joji Suzuki and Saria El-Haddad, “A Review: Fentanyl and Non-Pharmaceutical Fentanyls,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, Vol. 171, February 1, 2017, p. 107-116, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.11.033 However, fentanyl is relatively easy to produce in illicit labs and mix into other drugs, where its potency varies and as little as two milligrams can be lethal. United States Drug Enforcement Administration, “Facts About Fentanyl,” dea.gov, accessed August 9, 2023, https://www.dea.gov/resources/facts-about-fentanyl

The proliferation of fentanyl is the defining feature of the third, most lethal wave of the opioid epidemic, and it largely fueled the surge of fatal drug overdoses from 13.8 per 100,000 in 2013 to 21.6 in 2019. Christine L. Mattson, Lauren J. Tanz, Kelly Quinn, Mbabazi Kariisa, Priyam Patel and Nicole Davis, “Trends and Geographic Patterns in Drug and Synthetic Opioid Overdose Deaths — United States, 2013–2019,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 70, No. 6, February 12, 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/pdfs/mm7006a4-H.pdf During the COVID-19 pandemic, the fentanyl epidemic worsened. In 2019, opioids were involved in 49,860 overdose deaths (70.6% of all overdose deaths recorded), and 73% of these opioid-related deaths specifically involved synthetic opioids. By 2021, Christine L. Mattson, Lauren J. Tanz, Kelly Quinn, Mbabazi Kariisa, Priyam Patel and Nicole Davis, “Trends and Geographic Patterns in Drug and Synthetic Opioid Overdose Deaths — United States, 2013–2019,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 70, No. 6, February 12, 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/pdfs/mm7006a4-H.pdf opioids were involved in 80,411 overdose deaths (75.4% of all overdose deaths recorded), 88% of which specifically involved synthetic opioids. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Drug Overdose Deaths,” cdc.gov, updated August 22, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/deaths/index.html

The U.S. Fentanyl Epidemic

Available in liquid and powder forms, illicit fentanyl can be easily mixed into drugs like heroin, methamphetamines, and counterfeit pills. Fentanyl is cheaper to produce than heroin, Sarah G. Mars, Daniel Rosenblum, and Daniel Ciccarone, “Illicit Fentanyls in the Opioid Street Market: Desired or Imposed?” Addiction, Vol. 114, No. 5, May 2019, p. 774-780, doi: 10.1111/add.14474, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6548693/ and its higher potency increases profitability: an equivalent dose of fentanyl is as little as “1/300 or 1/400 of the wholesale price of heroin.” Often, illicit fentanyl is labeled and sold as heroin, and people who use drugs may be unaware that their drugs contain fentanyl. Sarah G. Mars, Daniel Rosenblum, and Daniel Ciccarone, “Illicit Fentanyls in the Opioid Street Market: Desired or Imposed?” Addiction, Vol. 114, No. 5, May 2019, p. 774-780, doi: 10.1111/add.14474, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6548693/ Most illicit fentanyl in the United States is smuggled into the country from Mexico, Commission on Combating Synthetic Opioid Trafficking, “Final Report,” rand.org, February 8, 2022, https://www.rand.org/pubs/external_publications/EP68838.html where cartels manufacture fentanyl products using ingredients and equipment imported from China. Commission on Combating Synthetic Opioid Trafficking, “Final Report,” rand.org, February 8, 2022, https://www.rand.org/pubs/external_publications/EP68838.html However, powder fentanyl, ingredients, and equipment are also increasingly available for purchase online, often from Mexican or Chinese labs, which are distributed within the U.S. through mail carriers. The Wilson Center Mexico Institute and InSight Crime, “Mexico’s Role in the Deadly Rise of Fentanyl,” wilsoncenter.org, February 2019, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/mexicos-role-the-deadly-rise-fentanyl

Regardless of the method, fentanyl trafficking has increased substantially in the past decade. The number of fentanyl trafficking offenders rose from nine in fiscal year (FY) 2014 to 433 in FY 2018, to 2,366 in FY 2022. United States Sentencing Commission, “Quick Facts - Federal Fentanyl Trafficking Offenses: Fiscal Year 2018,” ussc.gov, accessed August 10, 2023, https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/quick-facts/Fentanyl_FY18.pdf United States Sentencing Commission, “Quick Facts - Federal Fentanyl Trafficking Offenses: Fiscal Year 2022,” ussc.gov, accessed August 10, 2023, https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/quick-facts/Fentanyl_FY22.pdf

The U.S. has implemented strategies to thwart synthetic opioid trafficking into the country, such as providing $3.5 billion in security and counternarcotics aid to Mexico from 2008 to 2021, and sanctioning companies in Mexico and China for enabling the production of fentanyl-laced pills in May 2023. Claire Klobucista and Alejandra Martinez, “Fentanyl and the US Opioid Epidemic,” cfr.org, last updated April 19, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/fentanyl-and-us-opioid-epidemic US Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Sanctions China- And Mexico-Based Enablers of Counterfeit, Fentanyl-Laced Pill Production,” treasury.gov, May 30, 2023, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1507 Nonetheless, fentanyl remains pervasive in the U.S., and new drugs derived from fentanyl, called analogs, continue to emerge, such as carfentanil, remifentanil, and sufentanil. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “Fentanyl and Work,” cdc.gov, last reviewed February 27, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/fentanyl/default.html US Department of Justice, “Carfentanil: A Dangerous New Factor in the US Opioid Crisis,” justice.gov, accessed November 7, 2023, https://www.justice.gov/usao-edky/file/898991/download

As illicit fentanyl products flood the drug supply, users are increasingly and often unwittingly exposed to fentanyl and therefore vulnerable to overdosing. According to a 2017 survey of heroin and prescription opioid users, more than three-quarters of respondents suspected that their drugs had been laced with fentanyl without their knowledge at some point in the prior six months. Kenneth B. Morales, Ju Nyeong Park, Jennifer L. Glick, Saba Rouhani, Traci C. Green, and Susan G. Sherman, “Preference for Drugs Containing Fentanyl From a Cross-Sectional Survey of People Who Use Illicit Opioids in Three United States Cities,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, Vol. 204, November 1, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107547

However, the ongoing fentanyl crisis is also propelled by demand. Frequent opioid users can develop tolerance to a dose and require increasingly strong doses to experience the same high. Fentanyl’s potency makes it dangerous but also gives the drug a more intense “rush” than other opioids, and some users enthusiastically describe fentanyl as “bringing back an opioid euphoria lost to tolerance." Sarah G. Mars, Daniel Rosenblum, and Daniel Ciccarone, “Illicit Fentanyls in the Opioid Street Market: Desired or Imposed?” Addiction, Vol. 114, No. 5, May 2019, p. 774-780, doi: 10.1111/add.14474, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6548693/ Even if inadvertently used, fentanyl can cause users to develop a higher opioid tolerance that heroin alone can no longer satisfy. Sarah G. Mars, Daniel Rosenblum, and Daniel Ciccarone, “Illicit Fentanyls in the Opioid Street Market: Desired or Imposed?” Addiction, Vol. 114, No. 5, May 2019, p. 774-780, doi: 10.1111/add.14474, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6548693/ Kenneth B. Morales, Ju Nyeong Park, Jennifer L. Glick, Saba Rouhani, Traci C. Green, and Susan G. Sherman, “Preference for Drugs Containing Fentanyl From a Cross-Sectional Survey of People Who Use Illicit Opioids in Three United States Cities,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, Vol. 204, November 1, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107547

The short duration of its effects compounds fentanyl’s addictive qualities. While fentanyl’s initial “rush” is powerful, the resulting opioid euphoria is short-lived compared to other opioids, Barrot H. Lambdin, et al., “Associations Between Perceived Illicit Fentanyl Use and Infectious Disease Risks Among People Who Inject Drugs,” International Journal of Drug Policy, Vol. 74, December 2019, p. 299-304, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.10.004 often lasting “only 30 to 60 min for an intravenous injection, compared to 4-5h for heroin.” Nadia Fairbairn, et al., “Naloxone for Heroin, Prescription Opioid, and Illicitly Made Fentanyl Overdoses: Challenges and Innovations Responding to a Dynamic Epidemic,” International Journal of Drug Policy, Vol. 46, December 2019, p. 172-179, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0955395917301688

Consequently, maintaining a fentanyl high and avoiding withdrawal requires frequent use, thereby increasing the risk of exposure to a lethal dose. Sarah G. Mars, Daniel Rosenblum, and Daniel Ciccarone, “Illicit Fentanyls in the Opioid Street Market: Desired or Imposed?” Addiction, Vol. 114, No. 5, May 2019, p. 774-780, doi: 10.1111/add.14474, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6548693/ Ultimately, over 150 people die from overdoses involving synthetic opioids each day, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Fentanyl Facts,” cdc.gov, September 6, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/stopoverdose/fentanyl/index.html and in 2022 alone, the DEA seized over 379 million doses of fentanyl, enough to kill every American. Shawna Chen, “DEA Seized Enough Fentanyl in 2022 to Kill Everyone in the US,” axios.com, December 20, 2022, https://www.axios.com/2022/12/20/fentanyl-drug-dea-seizures-2022

Demographics of the fentanyl epidemic

Before the proliferation of illicit fentanyl around 2013, the difference between fentanyl-related overdose deaths in men versus women was marginal. However, the gap rapidly widened, and men have accounted for more than 70% of synthetic opioid-related fatal overdoses each year since 2016, primarily from fentanyl. National Institute on Drug Abuse, “Drug Overdose Death Rates,” nida.nih.gov, June 30, 2023, https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates

The fentanyl epidemic has also fueled a rapid increase in drug overdose deaths among Black Americans, particularly Black men. Bridget Kuehn, “Black Individuals Are Hardest Hit by Drug Overdose Death Increases,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 328, No, 8, p. 702-703, August 23/30, 2022, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2795517 Between 2015 and 2020, the drug overdose death rate tripled among Black men, rising from 17.3 per 100,000 in 2015 to 54.1 in 2020. John Gramlich, “Recent Surge in US Drug Overdose Deaths Has Hit Black Men the Hardest,” pewresearch.org, January 19, 2022, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/01/19/recent-surge-in-u-s-drug-overdose-deaths-has-hit-black-men-the-hardest/ For synthetic opioid overdose deaths specifically, the rate increased from 2.1 per 100,000 in 2015 to 24.1 in2020. National Institute on Drug Abuse, “Drug Overdose Death Rates,” nida.nih.gov, June 30, 2023, https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates In the same period, overdose fatalities rates more than doubled among Asian or Pacific Islander men (4.0 to 8.5), Hispanic men (10.9 to 27.3), and American Indian or Alaska Native men (25.8 to 52.1). John Gramlich, “Recent Surge in US Drug Overdose Deaths Has Hit Black Men the Hardest,” pewresearch.org, January 19, 2022, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/01/19/recent-surge-in-u-s-drug-overdose-deaths-has-hit-black-men-the-hardest/ Drug overdose death rates also increased among white men in that period, rising from 26.2 to 44.2. John Gramlich, “Recent Surge in US Drug Overdose Deaths Has Hit Black Men the Hardest,” pewresearch.org, January 19, 2022, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/01/19/recent-surge-in-u-s-drug-overdose-deaths-has-hit-black-men-the-hardest/ Increases in synthetic opioid-related deaths specifically increased as highlighted in the chart below.

Geography of the fentanyl epidemic

The Northeast and Appalachia remain the epicenters of the opioid crisis. In 2021, the states with the highest rates of drug overdose deaths involving opioids were primarily clustered in the Northeast and Appalachian states, including West Virginia (77.2 per 100,000 population), Delaware (48.1), Tennessee (45.5), Kentucky (44.8) and Maine (42.4). In the same year, the rate in D.C. was 48.9. KFF (The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation), “Opioid Overdose Death Rates and All Drug Overdose Death Rates per 100,000 Population (Age-Adjusted),” kff.org, accessed November 9, 2023, https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/opioid-overdose-death-rates

By comparison, in 2011, the rate of deaths involving opioids in those states were 31.5 per 100,000 population in West Virginia, 12.6 in Delaware, 10.1 in Tennessee, 15.8 in Kentucky and 6.7 in Maine. The rate in D.C. was 8.0. KFF (The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation), “Opioid Overdose Death Rates and All Drug Overdose Death Rates per 100,000 Population (Age-Adjusted),” kff.org, accessed November 9, 2023, https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/opioid-overdose-death-rates

The lowest rates of drug overdose deaths involving opioids in 2021 occurred in South Dakota (5.7 per 100,000 population), Nebraska (6.0) and Hawaii (6.1). KFF (The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation), “Opioid Overdose Death Rates and All Drug Overdose Death Rates per 100,000 Population (Age-Adjusted),” kff.org, accessed November 9, 2023, https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/opioid-overdose-death-rates In 2011, the lowest rates were in Louisiana (2.5), Nebraska (2.8) and Mississippi (2.9). KFF (The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation), “Opioid Overdose Death Rates and All Drug Overdose Death Rates per 100,000 Population (Age-Adjusted),” kff.org, accessed November 9, 2023, https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/opioid-overdose-death-rates Only in Oklahoma and Utah have the rates decreased between 2011 and 2021; 13.0 per 100,000 population to 12.1 and 14.6 to 14.1 respectively. KFF (The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation), “Opioid Overdose Death Rates and All Drug Overdose Death Rates per 100,000 Population (Age-Adjusted),” kff.org, accessed November 9, 2023, https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/opioid-overdose-death-rates

The opioid crisis did not hit all of the U.S. simultaneously. Public health trends typically reach states such as Alaska and Hawaii later than the contiguous United States, and the opioid crisis was no exception. Hawaii State Department of Health, “The Hawaii Opioid Initiative,” health.hawaii.gov, December 2017, https://health.hawaii.gov/substance-abuse/files/2013/05/The-Hawaii-Opioid-Initiative.pdf

California’s worsening fentanyl crisis

Although the epidemic remains concentrated in the Northeast and Appalachia, the fentanyl crisis began moving toward the West Coast after 2016. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “New Data Show Growing Complexity of Drug Overdose Deaths in America,” cdc.gov, December 21, 2018,https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2018/p1221-complexity-drug-overdose.html From 2019 onwards, fentanyl-related overdose deaths rose exponentially throughout California, increasing 365% from 2019 to 2021 California Department of Health Care Services, “California Response to the Overdose Crisis,” 2023, https://californiamat.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/MAT_Flyers_DHCS_Opioid_Crisis.pdf and causing the state’s total number of drug overdose deaths to nearly double. California Overdose Surveillance Dashboard, “California Dashboard,” skylab.cdph.ca.gov, accessed September 6, 2023, https://skylab.cdph.ca.gov/ODdash/?tab=CA

In the 12-month period ending May 2023, 62% of fatal drug overdoses in California involved synthetic opioids (excluding methadone). This percentage is lower than in 19 of the 20 Northeastern and Appalachian states with data available, where the average percentage is 79%. No data for Pennsylvania. Percentages range from 61% in Mississippi to 96% in North Carolina. See National Vital Statistics System, “Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts,” cdc.gov, accessed November 13, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm However, due to the population size of the state, the total number of overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids (excluding methadone) in California, was greater than that of New York, Massachusetts and Maryland combined. According to the National Vital Statistics System Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts, there were approximately 7,129 fatal overdoses involving synthetic opioids (excluding methadone) in California as of the 12-month period ending in May 2023, compared to 2,602 in New York, 2,198 in Massachusetts, and 2,045 in Maryland. See National Vital Statistics System, “Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts,” cdc.gov, accessed November 13, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

In California, northern, coastal parts of the state face disproportionately high rates of fatal overdoses involving fentanyl, but in terms of overall number of deaths, the fentanyl crisis is largely concentrated in large urban areas. Ana B. Ibarra, Erica Yee, and Nigel Duara, “California’s Opioid Deaths Increased by 121% In 3 Years. What’s Driving the Crisis?” calmatters.org, July 25, 2023, https://calmatters.org/explainers/california-opioid-crisis/ The pace of fentanyl overdoses has been particularly alarming in Los Angeles (L.A.) County, where fentanyl overdose deaths increased 1,280% from 109 deaths in 2016 to 1,504 in 2021. Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, “Data Report: Fentanyl Overdoses in Los Angeles County,” publichealth.lacounty.gov, October 2023 (updated), http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/sapc/MDU/SpecialReport/FentanylOverdosesInLosAngelesCounty.pdf In the same period, the proportion of fatal drug overdoses that involved fentanyl increased from 10% to 55%. Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, “Data Report: Fentanyl Overdoses in Los Angeles County,” publichealth.lacounty.gov, October 2023 (updated), http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/sapc/MDU/SpecialReport/FentanylOverdosesInLosAngelesCounty.pdf

The fentanyl epidemic’s impact on different demographic groups in L.A. County in 2021 was broadly consistent with national trends:

- Men account for most of L.A. County’s fentanyl deaths, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations, and men die from fentanyl overdoses at a rate 3.9 times higher than women. Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, “Data Report: Fentanyl Overdoses in Los Angeles County,” publichealth.lacounty.gov, October 2023 (updated), http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/sapc/MDU/SpecialReport/FentanylOverdosesInLosAngelesCounty.pdf

- Adults aged 26-39 accounted for 42% of L.A. County’s fatal overdoses involving fentanyl, and adults aged 40-64 comprised 38%. Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, “Data Report: Fentanyl Overdoses in Los Angeles County,” publichealth.lacounty.gov, October 2023 (updated), http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/sapc/MDU/SpecialReport/FentanylOverdosesInLosAngelesCounty.pdf

- The fentanyl overdose death rate for Black Angelenos (31.8 per 100,000 population) far exceeded that of their white (23.3) and Latino/a/x (11.5) counterparts, even though white and Latino/a/x people accounted for most overdose deaths. Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, “Data Report: Fentanyl Overdoses in Los Angeles County,” publichealth.lacounty.gov, October 2023 (updated),http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/sapc/MDU/SpecialReport/FentanylOverdosesInLosAngelesCounty.pdf

- In poorer areas, the rate of overdose deaths involving fentanyl was 39.6 per 100,000 population, compared to 12.4 in more affluent areas. “Poorer areas” refer to areas where more than 30% of families live below the federal poverty line, and “more affluent areas” are defined as areas where less than 10% live below the federal poverty line. See, Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, “Data Report: Fentanyl Overdoses in Los Angeles County,” publichealth.lacounty.gov, October 2023 (updated), http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/sapc/MDU/SpecialReport/FentanylOverdosesInLosAngelesCounty.pdf

The link between poverty and fentanyl overdose risk is not unique to Los Angeles. Nationwide, the fentanyl epidemic has disproportionately impacted lower-income communities and people experiencing homelessness. Marcella A. Kelley, Jonathan Lucas, Emily Stewart, Dana Goldman, and Jason Doctor, “Opioid-Related Deaths Before and After COVID-19 Stay-At-Home Orders in Los Angeles County,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, Vol. 228, November 1, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109028 Keith Humphreys, et al., “Responding to the Opioid Crisis in North America and Beyond: Recommendations of the Stanford-Lancet Commission,” Vol. 399, Issue 10324, February 5, 2022, p. 555-604, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02252-2 However, Los Angeles County has struggled with a homelessness crisis for decades, fueled by slow housing development, soaring rent prices, low wages, and insufficient public investments, among other factors, leading some to call Los Angeles the “‘homeless capital’ of the United States.” Kirsten Moore Sheely, Alisa Belinkoff Katz, Andrew Klein, Jessica Richards, Fernanda Jahn Verri, Marques Vestal, and Zev Yaroslavsky, “The Making of a Crisis: A History of Homelessness in Los Angeles,” UCLA Luskin Center for History and Policy, January 2021, https://luskincenter.history.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/66/2021/01/LCHP-The-Making-of-A-Crisis-Report.pdf As of 2023, an estimated 75,518 people experience homelessness on any given night in L.A. Country. Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, “LA’s Homeless Response Leaders Unite to Address Unsheltered Homelessness as Homeless Count Rises,” lahsa.org, June 29, 2023, https://www.lahsa.org/news?article=927-lahsa-releases-results-of-2023-greater-los-angeles-homeless-count

The Fentanyl Epidemic and the Homelessness Crisis in Los Angeles

In general, people experiencing homelessness face a greater risk of death and injury than the housed population. County of Los Angeles, “New Public Health Report Shows Sharp Rise in Mortality Among People Experiencing Homelessness,” lacounty.gov, May 12, 2023, https://lacounty.gov/2023/05/12/new-public-health-report-shows-sharp-rise-in-mortality-among-people-experiencing-homelessness/ Between 2016 and 2018, the mortality rate for L.A. County’s unhoused population was 2.3 times higher than that of the general population. Los Angeles County Department of Public Health Center for Health Impact Evaluation, “Recent Trends in Mortality Rates and Cause of Death Among People Experiencing Homelessness in Los Angeles County,” publichealth.lacounty.gov, October 2019, http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/chie/reports/HomelessMortality_CHIEBrief_Final.pdf By 2020 and 2021, the mortality rate for people experiencing homelessness had grown to 3.8 times greater than the general population. Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, “Mortality Rates and Causes of Death Among People Experiencing Homelessness in Los Angeles County 2014-2021,” publichealth.lacounty.gov, May 2023, http://www.publichealth.lacounty.gov/chie/reports/Homeless_Mortality_Report_2023.pdf

Drug overdoses accounted for more than one-third of all deaths among people experiencing homelessness in L.A. County from 2020 to 2021, and unhoused individuals were 38.9 times more likely to die of a drug overdose than the housed population. Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, “Mortality Rates and Causes of Death Among People Experiencing Homelessness in Los Angeles County 2014-2021,” publichealth.lacounty.gov, May 2023, http://www.publichealth.lacounty.gov/chie/reports/Homeless_Mortality_Report_2023.pdf Fentanyl bears primary responsibility for rising mortality rates and overdose deaths, as fentanyl-related overdose deaths nearly tripled from 2019 to 2021 among L.A. County’s unhoused population. Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, “Mortality Rates and Causes of Death Among People Experiencing Homelessness in Los Angeles County 2014-2021,” publichealth.lacounty.gov, May 2023, http://www.publichealth.lacounty.gov/chie/reports/Homeless_Mortality_Report_2023.pdf

In Skid Row, a downtown Los Angeles neighborhood long known as the center of the city’s homelessness crisis, the fentanyl epidemic has been devastating. Fatal drug overdoses increased more than eleven-fold in Skid Row and nearby areas from 2017 to 2022, rising from 13 deaths to 148, and more than 70% of the deaths involved fentanyl. Noah Goldberg and Ruben Vives, “Fentanyl Blamed for Surge in Overdose Deaths in and Around Skid Row, According to New Data,” latimes.com, August 31, 2023, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-08-31/overdoses-surge-especially-inside-apartments-near-skid-row According to one resident, fentanyl overdoses have “become the norm here.” Ruben Vives, “Overdose Deaths at Skid Row Housing Trust Building Hint at Wider Problem,” latimes.com, April 7, 2023, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-04-07/la-me-skid-row-overdoses-residents

Mental health issues and substance use among L.A.’s unhoused population

The fentanyl epidemic’s extreme impact on unhoused communities can be attributed, in part, to the higher prevalence of substance use disorders among people experiencing homelessness than the housed population. Emily Alpert Reyes, “Fentanyl Overdoses Contribute To Surge in LA County Homeless Deaths,” latimes.com, May 12, 2023, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-05-12/deaths-homeless-la-county-overdoses-fentanyl In 2023, the Los Angeles Homeless Services authority reported that 30% of people experiencing homelessness have a substance use disorder, Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, “2023 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count Deck,” lahsa.org, June 29, 2023, https://www.lahsa.org/documents?id=7232-2023-greater-los-angeles-homeless-count-deck but the prevalence may be higher. In 2019, LAHSA reported that 14% of people experiencing homelessness suffered from substance use disorder, but an independent Los Angeles Times investigation found that LAHSA was interpreting survey responses narrowly, and they estimated that 46% of people experiencing homelessness had a substance use disorder. See: Doug Smith and Benjamin Oreskes, “Are Many Homeless People in L.A. Mentally Ill? New Findings Back the Public’s Perception,” latimes.com, October 7, 2019, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2019-10-07/homeless-population-mental-illness-disability and Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, “2019 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count Los Angeles Continuum of Care,” lahsa.org, July 29, 2019, https://www.lahsa.org/documents?id=3422-2019-greater-los-angeles-homeless-count-los-angeles-continuum-of-care.pdf In a 2021 survey published in the Journal of Substance Use, 63.7% of people experiencing homelessness in Skid Row admitted using drugs but did not necessarily have a substance use disorder. Adeline M. Nyamathi, et al, “Correlates of Substance Use Disorder Among Persons Experiencing Homelessness in Los Angeles During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Journal of Substance Use, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2023.2197051

Unhoused individuals also suffer from mental health conditions at higher rates than the housed population, with as many as 51% of Los Angeles’ unhoused population having a mental illness. Faith E. Pinho, “How To Help a Stranger on the Street in a Mental Health Crisis,” latimes.com, September 22, 2022, https://www.latimes.com/homeless-housing/story/2022-01-19/how-to-help-a-homeless-person-in-crisis The very process of becoming homeless can be traumatic, and the daily stressors of homelessness, such as ensuring safety or securing food, can cause or worsen mental health conditions. Stacy M. Deck and Phyllis A. Platt, “Homelessness Is Traumatic: Abuse, Victimization, and Trauma Histories of Homeless Men,” Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, Vol. 24, Issue 9, 2015, p. 1022-1043, https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2015.1074134 In places like Skid Row, where accessing mental health services can be difficult, past traumas and the psychological distress of experiencing homelessness lead some to use drugs to cope. Emily Alpert Reyes, “Fentanyl Overdoses Contribute To Surge in LA County Homeless Deaths,” latimes.com, May 12, 2023, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-05-12/deaths-homeless-la-county-overdoses-fentanyl Noah Goldberg and Ruben Vives, “Fentanyl Blamed for Surge in Overdose Deaths in and Around Skid Row, According to New Data,” latimes.com, August 31, 2023, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-08-31/overdoses-surge-especially-inside-apartments-near-skid-row

Isolation, marginalization, and poor access to resources

In April 2023, a woman in Skid Row called paramedics for a man in a nearby tent who was screaming for help, but paramedics refused to enter his tent. Ruben Vives, “Overdose Deaths at Skid Row Housing Trust Building Hint at Wider Problem,” latimes.com, April 7, 2023, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-04-07/la-me-skid-row-overdoses-residents The man’s brother found him hours later not breathing, and although he administered Narcan, his brother did not wake up. Ruben Vives, “Overdose Deaths at Skid Row Housing Trust Building Hint at Wider Problem,” latimes.com, April 7, 2023, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-04-07/la-me-skid-row-overdoses-residents When coroner officials arrived, they suspected it could be a fentanyl overdose. Ruben Vives, “Overdose Deaths at Skid Row Housing Trust Building Hint at Wider Problem,” latimes.com, April 7, 2023, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-04-07/la-me-skid-row-overdoses-residents

It is unclear why paramedics did not help this man, but this case is not an anomaly. People experiencing homelessness face significant obstacles to receiving care. The problem is particularly acute in unhoused communities like Skid Row, where isolation from social and health services can make it less likely that someone will intervene in the event of an overdose.Emily Alpert Reyes, “Fentanyl Overdoses Contribute To Surge in LA County Homeless Deaths,” latimes.com, May 12, 2023, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-05-12/deaths-homeless-la-county-overdoses-fentanyl

People experiencing homelessness are also less likely to be able to access Narcan, a naloxone nasal spray that can reverse an opioid overdose. Until recently, Narcan has required a prescription, making it difficult for unhoused individuals to obtain. Berkeley Lovelace Jr., “Over-The-Counter Narcan To Cost Less Than $50 for a Two-Pack, Company Says,” nbcnews.com, April 20, 2023, https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/over-counter-narcan-cost-opioid-overdose-drug-rcna80665 Although Narcan is now available to purchase at drug stores without a prescription, a package containing two doses costs $44.99, Sabrina Moreno, “Narcan Is Coming to Drug Store Shelves — For Those Who Can Afford It,” axios.com, August 30, 2023, https://www.axios.com/2023/08/30/narcan-price-otc-overdose and severe overdoses may require multiple doses. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), “Naloxone Drug Facts,” nida.nih.gov, January 2022, https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/naloxone For many unhoused individuals, purchasing the overdose reversal agent is not an option.

Some people experiencing homelessness can obtain naloxone for free from nonprofits, community centers, and local health departments. However, these programs are often scantily funded, and getting enough naloxone to people experiencing homelessness can be challenging, as it often involves seeking out and directly distributing it to unhoused individuals. Emily Alpert Reyes, “Amid an Overdose Crisis, a California Grant That Helped Syringe Programs Is Drying Up,” latimes.com, February 19, 2023, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-02-19/overdose-california-grant-syringe-programs

Although fentanyl test strips can be valuable tools to check drugs for fentanyl and prevent unintended exposure, they are often impractical and difficult to use for unhoused individuals. While test strips are generally highly accurate, people experiencing homelessness often do not have reliable access to clean water to administer the test, leaving them vulnerable to unintended fentanyl exposure. Emily Alpert Reyes, “Fentanyl Overdoses Contribute To Surge in LA County Homeless Deaths,” latimes.com, May 12, 2023, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-05-12/deaths-homeless-la-county-overdoses-fentanyl

COVID-19 and the fentanyl epidemic

Fentanyl had already saturated the Los Angeles drug supply when the COVID-19 pandemic began, and fatal overdoses were surging. Measures that were intended to stop the spread of COVID-19 inadvertently compounded the isolation and stress that people experiencing homelessness already faced and may have contributed to higher rates of substance use. Adeline M. Nyamathi, et al, “Correlates of Substance Use Disorder Among Persons Experiencing Homelessness in Los Angeles During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Journal of Substance Use, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2023.2197051

Shutdowns and mandatory quarantines likely created significant obstacles for those taking medications to treat a mental health condition or substance use disorder, placing them at greater risk of relapse or drug use. Adeline M. Nyamathi, et al, “Correlates of Substance Use Disorder Among Persons Experiencing Homelessness in Los Angeles During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Journal of Substance Use, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2023.2197051 Simultaneously, naloxone and test strip distribution slowed as fewer people were available to distribute it, community centers were forced to close doors, and mental health and addiction services were disrupted. Adeline M. Nyamathi, et al, “Correlates of Substance Use Disorder Among Persons Experiencing Homelessness in Los Angeles During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Journal of Substance Use, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2023.2197051

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the stressful conditions of homelessness and made the already difficult task of accessing services nearly impossible. Los Angeles County’s thousands of unhoused residents were left even more vulnerable to the burgeoning fentanyl epidemic, and more people experiencing homelessness died from drug overdoses in 2020-2021 than the “six previous years combined." Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, “Mortality Rates and Causes of Death Among People Experiencing Homelessness in Los Angeles County 2014-2021,” publichealth.lacounty.gov, May 2023, http://www.publichealth.lacounty.gov/chie/reports/Homeless_Mortality_Report_2023.pdf While most pandemic-related restrictions and closures have eased, the fentanyl epidemic shows few signs of slowing.

Solutions

Given fentanyl’s lethality and the epidemic’s shocking growth, law enforcement, policymakers, and political leaders have been scrambling to slow down and prevent overdoses.

Considering that people experiencing homelessness in LA County were 38.9 more likely to die from a drug overdose than the housed population, any initiative that can improve access to health care, social services, and housing could be effective at slowing down overdose deaths among the unhoused. In Los Angeles, for example, the newly elected mayor has championed Inside Safe, a strategy that aims to help get people experiencing homelessness into housing and increase access to mental health and substance abuse treatment. Mayor Karen Bass, City of Los Angeles, “Mayor Bass Signs Executive Directive Launching Inside Safe Changing the City’s Encampment Approach,” mayor.lacity.gov, December 21, 2022, https://mayor.lacity.gov/news/mayor-bass-signs-executive-directive-launching-inside-safe-changing-citys-encampment-approach Mayor Karen Bass, City of Los Angeles, “Inside Safe Effort Launched in South Los Angeles,” mayor.lacity.gov, August 3, 2023, https://mayor.lacity.gov/news/inside-safe-effort-launched-south-los-angeles

The strategy has so far struggled to make significant headway as bureaucratic rules and slow housing development create bottlenecks, but planned improvements to the program and expanded funding may help in the future. Marisa Kendall, “LA’s New Homeless Solution Clears Camps but Struggles to House People,” calmatters.org, July 13, 2023, https://calmatters.org/housing/homelessness/2023/07/los-angeles-homeless-encampments/

Ultimately, putting an end to the opioid crisis will likely require significant investments in affordable housing, health care, mental health services, and substance use treatment. Keith Humphreys, et al., “Responding to the Opioid Crisis in North America and Beyond: Recommendations of the Stanford-Lancet Commission,” Vol. 399, Issue 10324, February 5, 2022, p. 555-604, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02252-2 These structural changes typically happen slowly, if at all. In the meantime, large-scale Narcan distribution efforts could be a promising strategy to prevent opioid overdose deaths. The FDA-approved naloxone nasal spray is easy to administer, highly effective at reversing opioid overdoses, and can have an immediate impact. Nadia Kounang, “Naloxone Reverses 93% of Overdoses,” cnn.com, October 30, 2017, https://www.cnn.com/2017/10/30/health/naloxone-reversal-success-study/index.html According to a review of Massachusetts emergency medical services data from 2013 to 2015, 93.5% of those who overdosed on an opioid survived when given naloxone. Nadia Kounang, “Naloxone Reverses 93% of Overdoses,” cnn.com, October 30, 2017, https://www.cnn.com/2017/10/30/health/naloxone-reversal-success-study/index.html

Naloxone is often inaccessible to those at the highest risk of overdose, and the rising prevalence of drugs containing fentanyl and a veterinary tranquilizer called xylazine, or tranq, poses an additional challenge. Jaysha Patel, “What Is Tranq? Recent Skid Row Deaths Raise Concerns About Dangerous ‘Zombie Drug’ Xylazine,” abc7.com, April 6, 2023, https://abc7.com/downtown-los-angeles-skid-row-deaths-3-people-found-dead-649-lofts/13095868/ For some, xylazine is desirable because it reportedly prolongs fentanyl’s euphoric effects and staves off withdrawal symptoms for longer. Claire M. Zagorski, et al., “Reducing the Harms of Xylazine: Clinical Approaches, Research Deficits, and Public Health Context,” Harm Reduction Journal, Vol. 20, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-023-00879-7 However, xylazine can cause difficulty breathing, dangerously low blood pressure, sedation, and death, and since it is not an opioid, naloxone cannot reverse its effects. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “What You Should Know About Xylazine,” cdc.gov, July 17, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/deaths/other-drugs/xylazine/faq.html In 2022, the DEA reported that 23% of lab-tested fentanyl powder samples and 7% of fentanyl pills seized contained xylazine. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “What You Should Know About Xylazine,” cdc.gov, July 17, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/deaths/other-drugs/xylazine/faq.html With xylazine’s increasing prevalence, public health experts worry that naloxone may be less effective in reversing overdoses. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “What You Should Know About Xylazine,” cdc.gov, July 17, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/deaths/other-drugs/xylazine/faq.html

A less expensive strategy for preventing fatal overdoses involves distributing fentanyl test strips, which can accurately detect fentanyl in drug samples and are unlikely to produce false negatives. California Department of Public Health, “Fentanyl Testing to Prevent Overdose,” cdph.ca.gov, accessed September 26, 2023, https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DOA/CDPH%20Document%20Library/Fact_Sheet_Fentanyl_Testing_Approved_ADA.pdf Fentanyl test strips can be purchased for as little as $1, and they are often given out freely at community centers, nonprofits, and health clinics. California Department of Public Health, “Fentanyl and Fentanyl Test Strips FAQ,” cdph.ca.gov, 2023, https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CCDPHP/sapb/CDPH%20Document%20Library/FentanylTestStrips_FAQs.pdf As noted above, people experiencing homelessness may not be able to consistently use them. In addition, fentanyl test strips do not measure quantity or potency, and their detection threshold is very low, meaning a drug that does not contain fentanyl may test positive if it was packaged in the same area as a drug containing fentanyl. California Department of Public Health, “Fentanyl and Fentanyl Test Strips FAQ,” cdph.ca.gov, 2023, https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CCDPHP/sapb/CDPH%20Document%20Library/FentanylTestStrips_FAQs.pdf Fentanyl test strips also cannot detect xylazine, and while there are separate xylazine test strips, they are not yet widely available. Jaysha Patel, “What Is Tranq? Recent Skid Row Deaths Raise Concerns About Dangerous ‘Zombie Drug’ Xylazine,” abc7.com, April 6, 2023, https://abc7.com/downtown-los-angeles-skid-row-deaths-3-people-found-dead-649-lofts/13095868/

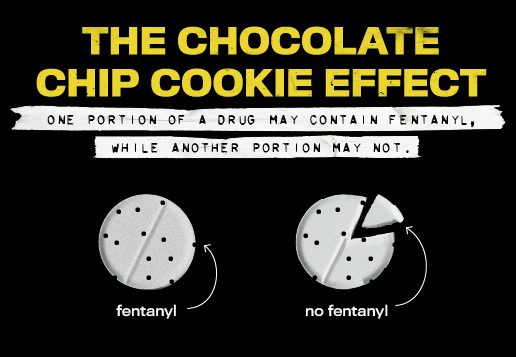

The effectiveness of test strips is also diminished by the “chocolate chip cookie effect.” To test a drug for fentanyl, a test strip is immersed for 15 seconds in a container with a small amount of the drug and half a teaspoon of water and then left to dry for two to five minutes. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Fentanyl Test Strips: A Harm Reduction Strategy,” cdc.gov, last reviewed September 30, 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/stopoverdose/fentanyl/fentanyl-test-strips.html If the drug sample contains fentanyl, a pink line appears on the left side of the strip, and two pink lines indicate a negative result. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Fentanyl Test Strips: A Harm Reduction Strategy,” cdc.gov, last reviewed September 30, 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/stopoverdose/fentanyl/fentanyl-test-strips.html When fentanyl is mixed into a drug, such as heroin or cocaine, the fentanyl is not evenly distributed. California Department of Public Health, “Fentanyl and Fentanyl Test Strips FAQ,” cdph.ca.gov, 2023, https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CCDPHP/sapb/CDPH%20Document%20Library/FentanylTestStrips_FAQs.pdf In other words, one portion of a pill or bag of powder may contain a lethal amount of fentanyl, while another part contains none. To overcome the “chocolate chip cookie effect,” drugs must be tested multiple times with samples from different portions of the product.

Still, making test strips and naloxone more accessible is imperative, and several state and local governments have created programs to do so. The California Department of Health Care Services created the Naloxone Distribution Project (NDP), which provides free naloxone to public health agencies, first responders, schools, homeless programs, community organizations, and other organizations. California Department of Health Care Services, “Naloxone Distribution Project,” californiaopioidresponse.org, accessed November 14, 2023, https://californiaopioidresponse.org/matproject/naloxone-distribution-project/ Since 2018, the NDP has distributed more than three million naloxone kits across the state, and over 211,000 overdoses have been reversed. California Department of Health Care Services, “Naloxone Distribution Project,” californiaopioidresponse.org, accessed November 14, 2023, https://californiaopioidresponse.org/matproject/naloxone-distribution-project/ In March 2023, California Governor Gavin Newsom announced a plan to allocate $79 million to continue distributing naloxone, $10 million for education and testing, and another $4 million to distribute fentanyl test strips. Office of Governor Gavin Newsom, “Governor Newsom Releases Master Plan for Tackling the Fentanyl and Opioid Crisis,” gov.ca.gov, March 20, 2023, https://www.gov.ca.gov/2023/03/20/master-plan-for-tackling-the-fentanyl-and-opioid-crisis/

At the federal level, the Biden Administration’s National Drug Control Strategy calls for expanding harm reduction interventions like naloxone and fentanyl test strip distribution and boosting federal-state cooperation. The White House, “Fact Sheet: White House Releases 2022 National Drug Control Strategy that Outlines Comprehensive Path Forward to Address Addiction and the Overdose Epidemic,” whitehouse.gov, April 21, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/04/21/fact-sheet-white-house-releases-2022-national-drug-control-strategy-that-outlines-comprehensive-path-forward-to-address-addiction-and-the-overdose-epidemic/ Simultaneously, the Strategy also prioritizes thwarting drug trafficking and disrupting distribution networks with calls to crack down on criminal financial networks and increase funding for the DEA and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). The White House, “Fact Sheet: White House Releases 2022 National Drug Control Strategy that Outlines Comprehensive Path Forward to Address Addiction and the Overdose Epidemic,” whitehouse.gov, April 21, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/04/21/fact-sheet-white-house-releases-2022-national-drug-control-strategy-that-outlines-comprehensive-path-forward-to-address-addiction-and-the-overdose-epidemic/ Biden reiterated his commitment to tackling the fentanyl crisis in November 2023 with plans to make treatment more accessible and focus on international cooperation, including a deal with China to curb the export of chemicals used to make fentanyl. Bernd Debusmann Jr., “Can Joe Biden's Plan Stop the Flow of Fentanyl to the US?,” bbc.com, November 21, 2023 https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-67489395

“Fentanyl is... an issue that’s hurting families in every state across the nation," Biden said in a speech. "It really is an American tragedy.” C-SPAN, “President Biden Holds Meeting on Fentanyl Trafficking,” c-span.org, November 21, 2023 https://www.c-span.org/video/?531998-1/president-biden-holds-meeting-fentanyl-trafficking

Efforts to disrupt distribution networks have also been introduced at the state level. For example, Governor Gavin Newsom announced the expansion of California’s National Guard’s partnership with CBP to seize fentanyl at the U.S.-Mexico border and “develop informational analysis on organized criminal activity.” Office of Governor Gavin Newsom, “Governor Newsom Increases California National Guard Presence at the Border To Crack Down on Fentanyl Smugglers,” gov.ca.gov, September 7, 2023, https://www.gov.ca.gov/2023/09/07/governor-newsom-increases-calguard-at-border/

Another controversial tactic involves charging drug dealers with murder for selling or providing fentanyl products to individuals who have fatally overdosed, and around 30 states now have statutes that allow prosecutors to charge someone with homicide for selling or providing a lethal dose of fentanyl. Jan Hoffman, “Harsh New Fentanyl Laws Ignite Debate Over How to Combat Overdose Crisis,” nytimes.com, June 21, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/21/health/fentanyl-overdose-crisis.html This harsh law enforcement approach is meant to punish drug dealers and deter others from using drugs, but public health experts worry that the strategy could make things much worse. Gabe Stern, James Pollard, and Geoff Mulvihill, “State Lawmakers Consider Harsher Penalties for Fentanyl Possession,” pbs.org, March 20, 2023, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/state-lawmakers-consider-harsher-penalties-for-fentanyl-related-crimes

Instead of dismantling distribution networks, harsh criminal penalties may likely only impact low-level dealers or users who share a dose with a friend. Jan Hoffman, “Harsh New Fentanyl Laws Ignite Debate Over How to Combat Overdose Crisis,” nytimes.com, June 21, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/21/health/fentanyl-overdose-crisis.html Incarcerating these individuals can make it more difficult for people to recover from addiction: people in prison often still have access to drugs, do not receive adequate addiction treatment, and once released, a criminal history will make it harder to find work. Gabe Stern, James Pollard, and Geoff Mulvihill, “State Lawmakers Consider Harsher Penalties for Fentanyl Possession,” pbs.org, March 20, 2023, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/state-lawmakers-consider-harsher-penalties-for-fentanyl-related-crimes Further, fear of criminal charges could make it less likely that someone will report an overdose and receive potentially life-saving help. Jan Hoffman, “Harsh New Fentanyl Laws Ignite Debate Over How to Combat Overdose Crisis,” nytimes.com, June 21, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/21/health/fentanyl-overdose-crisis.html

Conclusion

Nearly three decades after the first surge of prescription opioid overdose deaths, the United States remains embroiled in an opioid crisis. In 2021 alone, 80,411 people died from a drug overdose that involved an opioid. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Drug Overdose Deaths,” cdc.gov, August 22, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/deaths/index.html Provisional data for 2022 put that number at 79,770; a 0.8% decrease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Provisional Data Shows US Drug Overdose Deaths Top 100,000 in 2022,” cdc.gov, May 18, 2023, https://blogs.cdc.gov/nchs/2023/05/18/7365/ Illicitly manufactured synthetic opioids like fentanyl are fueling the ongoing lethal phase of the opioid crisis. With a potency 50 to 100 times stronger than heroin or morphine, fentanyl is extremely addictive, and even small doses can be deadly. Although the fentanyl epidemic has spared no demographic or socioeconomic group, low income individuals and people experiencing homelessness face the highest risk of fatally overdosing.

Naloxone and fentanyl test strip distribution programs are imperative and can help thwart the unrelenting pace of fentanyl-related overdose deaths. However, fentanyl’s devastating impacts in Los Angeles, particularly among people experiencing homelessness, make it clear that getting help to those who need it most is easier said than done.

This report aimed to investigate the causes of the fentanyl epidemic and the conditions that have made it so lethal. By looking at the market dynamics of fentanyl as it has saturated the drug supply, it appears that cracking down on fentanyl dealing may not be enough, and saving lives depends on addressing opioid addiction. Treating addiction and preventing opioid overdose deaths involves improving access to mental health and substance use treatment, but likely also requires substantial public investments in health care and affordable housing.