By Celeste Benitez, Cooper Conway and Declan Maddern, in partnership with the Pepperdine University School of Public Policy

Introduction and Problem Statement

California has remained a state with one of the highest rates of homelessness in the United States. As of today, the City of Los Angeles is projected to have the most unhoused inhabitants in the state per 100,000 people (de Sousa et al., 2023). In 2023, the City of Los Angeles saw a 10% increase in homelessness, with an estimated 46,260 unhoused inhabitants (LAHSA, 2023)1. Homelessness in Los Angeles is a multifaceted policy issue that impacts multiple stakeholders and comes with many public costs, from increased crime rates and drug use to overburdening healthcare systems (Unity Parenting & Counseling, 2021). Addressing homelessness goes beyond creating short-term and long-term housing accommodations, as it is an issue that touches on accessibility to mental health services, substance abuse support, public safety concerns, and incarceration rates.

This crisis has led legislators and policymakers in California to invest billions of dollars in projects to move people from living on the streets to interim housing options. One of these interim housing options includes the construction of tiny home villages, a relatively new mechanism with the potential to reduce rates of homelessness in Los Angeles. In February 2021, the City of Los Angeles began building tiny home villages, also referred to as cabin communities, to increase short-term housing options for people experiencing homelessness. This decision was made as tiny home villages are thought to be a cost-friendly and dignified method of addressing high rates of homelessness. Tiny home villages are small in size, approximately 64 square feet, but offer unhoused people a private space in which they have autonomy (Pallet, 2024). Eleven tiny home villages have been built in the City of Los Angeles. The question, however, remains whether these villages are truly an effective solution for the homelessness and housing issues in the city. Answering this question requires researchers to evaluate the full costs and benefits of building, maintaining, and operating tiny home villages.

1 The former refers to a lack of consistent housing for a period of usually less than a month, whilst the latter requires an individual to be unhoused for either a year continuously or on four occasions over a three-year period, usually with a long-term disability that impedes their ability to live independently (Davalos & Kimberlin 2023, p. 2).

Hope the Mission staff and case workers at Whitsett West Tiny Home Village Photo: Ron Hall

Background and Literature Review

Defined as “rotational stays in emergency shelters; living in places not intended for human habitation such as vehicles; precarious arrangements in homeless encampments; ‘couch surfing’ at the homes of friends, family, and strangers; or living on the streets,” homelessness is on the rise across the country. Los Angeles County saw a 9% increase in 2023 from 2022 figures, totaling 75,518 people as of January 26th, 2023 (Evans, 2020, p. 361; LAHSA, 2023). Of these individuals, 46,260 were in the City of Los Angeles, which had a 10% increase over the same period of time (Ibid). This increase has been attributed to the rising cost of living and poverty rate, sharp rent increases and subsequently less available affordable housing, a lack of adequate social services, substance abuse, and a “rising tide of evictions,” sometimes with only five days warning, or even less (Thornton, 2023; Evans, 2020, p. 361; LAHSA, 2023). Roughly 64% of these individuals are experiencing short-term homelessness, while the remaining 36% are experiencing chronic homelessness, defined as being “unhoused continuously for a year or on at least four occasions within a three-year period” (Davalos & Kimberlin, 2023, p. 2).

Homelessness is more than a lack of housing; it has further adverse outcomes for the individual and the community at large. Without a home, gaining employment and access to healthcare is far more difficult (Unity Parenting and Counseling, 2023). This creates a cycle of helplessness, as unemployment and lack of physical and mental healthcare often prevent individuals from securing housing (Ibid; Jackson et al. 2020, p. 2). Homelessness also often leads to the worsening of health conditions. When unhoused individuals are admitted to hospitals, their conditions tend to be much worse and their hospital stays longer, with costs being passed onto the taxpayer (Unity Parenting and Counseling, 2021). Many may also attempt to self-medicate through the use of drugs and alcohol, endangering public safety and dissuading tourism. Lastly, incarceration costs fall on the public when individuals commit crimes or prove dangerous (Ibid.).

To combat this, all levels of government have implemented various strategies to prevent and reduce homelessness, from subsidizing housing to increasing incomes. At the federal level, part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act was specifically concerned with preventing a rise in homelessness in response to the pandemic by delaying evictions, providing a one-time cash payment and increasing unemployment benefits (Congress, 2024). At the state level, California introduced Proposition HHH in 2016, which provided city officials with $1.2 billion in bonds to build temporary and permanent housing (Local Housing Solutions, 2024). Similarly, the recently passed Proposition 1 has allocated $6.38 billion in bonds to construct mental health treatment facilities and provide supportive housing for unhoused individuals suffering from mental health or substance abuse issues (California Official Voter Information Guide, 2024).

However, their expensive nature and lack of tangible results have intensified scrutiny of these policies. Despite spending $20 billion over the last five years, homelessness continues to rise (California Official Voter Information Guide, 2024). While Proposition HHH supported the development of 7,000 supportive housing units, it also resulted in a drastic increase in construction costs per unit, rising to $531,000 from $350,000. It also slowed project development considerably due to the need for more qualified developers (Local Housing Solutions, 2024). These policy failures have motivated the implementation of more innovative solutions, like “tiny home” communities: small units to be lived in temporarily, usually ranging in size from 50 to 400 square feet, that take advantage of land deemed by the city to be “too small or poorly situated for a standard apartment building or single-family home,” and provide essentials like bedding, electricity, and heating and cooling all within a safe, locked space for those who lack permanent housing (LASHA 2023; Bozorg & Miller, 2014, p. 129; Schlepp, 2022; Evans, 2018, p. 34; Evans, 2020, p. 364).

Expenses vary greatly: a 2020 study estimated the national average cost of constructing a single unit to be $21,160, but the A-Mark Foundation estimates the average construction cost of a tiny home unit in Los Angeles County to be about $43,000, with a further $55 per night required for services and maintenance (Evans, 2020, p. 364; A-Mark Foundation, 2022). Tiny homes have been used by other parts of California, like Santa Clara County, as a strategy to provide temporary shelter, treatment, services, and, eventually, permanent housing (County of Santa Clara, 2023). Upon their preliminary analysis, the county found a decrease in homelessness rates and an increase in rates of those who attained permanent housing through interim housing initiatives (County of Santa Clara, 2023).

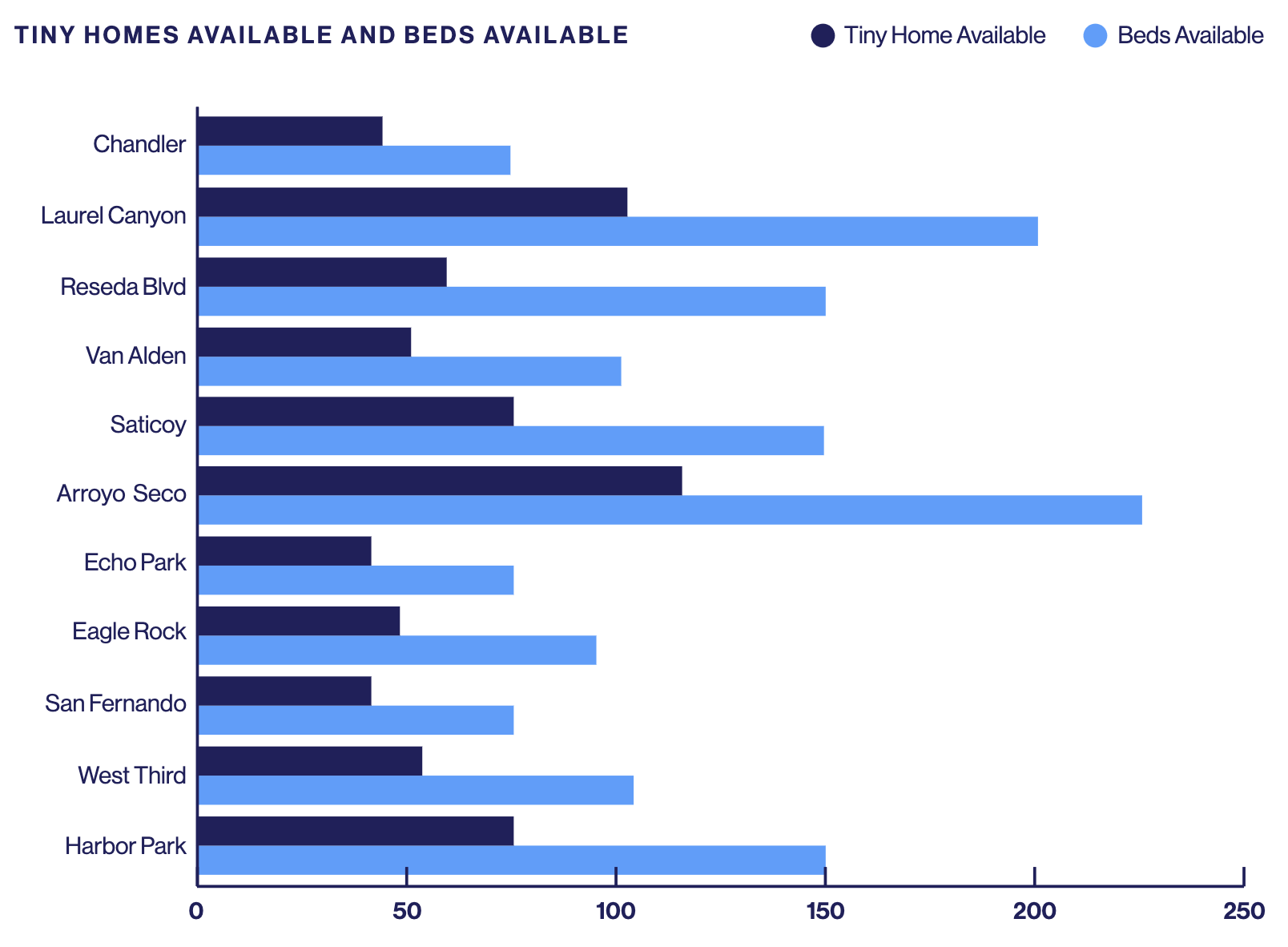

In Los Angeles, crucial services are allocated and provided through the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA), a joint-powers authority that consolidates city, county, and federal funds and includes health care, job training, mail services, and resources to obtain permanent housing (LASHA, 2023). These communities are seen as an attractive solution to homelessness because “they are relatively affordable, quick to build, more sustainable and environmentally friendly, and more dignified than congregate shelter options,” and are based upon the understanding that “stable housing is needed for homeless people to address issues such as job placement or addiction issues” (Calhoun, 2022, p. 239; Evans, 2020, p. 362). Current research identifies thriving tiny home communities as those with “strong community, public support, funding with few restrictions, and affordable housing options post-graduation” (Wong et al., 2020, p. 1). LA County currently operates 11 tiny home communities that house unhoused individuals, all operated by LAHSA, and has allocated $163.3 million to interim housing for the 2022-2023 fiscal year (LA County, 2023). The structure is provided by Pallet Shelter, a private company that markets itself on its rapid construction and end-to-end service delivery (Pallet Shelter, 2024). The Chandler, Echo Park Lake, Saticoy (Whitsett West), Laurel Canyon (Alexandria Park), Van Alden, Reseda Boulevard (Topham/Tarzana), and Arroyo Seco locations all opened in 2021, the West Third (Westlake), Harbor Park, and Eagle Rock locations in 2022, and the San Fernando community in 2023 (Figure 1, Tiny Homes Available and Beds Available).

While constructing more tiny home communities is planned, restrictive zoning laws that prohibit high-density development, limit the number of dwelling units per parcel, and establish a minimum household size complicate selecting locations for future developments (Jackson et al., 2020, p. 4).

These communities are an integral part of Los Angeles Mayor Bass’s “Inside Safe” program, “which place[s] homeless people temporarily … with the goal of getting them permanent housing and services to build lives off the streets, with resources for substance abuse and mental health counseling” (Grover, 2023). However, it is unclear whether this program has been successful: after a year of implementation, Mayor Bass herself reported an 83% housing retention rate2, and that “more than 14,000 people moved from L.A.’s streets to interim or permanent housing, with over 4,300 obtaining permanent housing”, and “[m] ore than 1,300 of those placements [coming] through the mayor’s Inside Safe program” (Zahniser, 2023; LAHSA, 2023). However, alternate reports have concluded that only 255 people have found permanent housing through this program, likely due to differing understanding of how the program contributed to obtaining such housing (Grover, 2023). Rowan Vansleve, the President of Hope the Mission— a non-profit organization that runs four of these communities—reports that an average of 11 to 14 people move from the North Hollywood communities— which currently offer a total of 326 beds— to permanent housing every month (Lyster, 2023).

A commonly reported issue is not with the housing itself, but the lack of support services provided, despite the promises of caseworkers to assist in finding permanent housing and access to mental health professionals (Ibid). Lack of the latter has contributed to 170 calls to emergency services in a single community from January to August of 2023, responding to assaults, threats, weapons, suicides, and overdoses (Lyster, 2023). Without these support systems, it is challenging for individuals to secure permanent housing on their own, resulting in a prolonged reliance on temporary housing and thus preventing new residents from moving into these tiny homes (Lyster, 2023; Grover, 2023). Because there is no time limit on how long residents can stay in these communities, legal experts fear that rather than being treated as temporary housing, these communities are becoming permanent residences for many who are not receiving adequate support (Giles, 2021; Lyster, 2023).

Due to these concerns, it has been argued that funding could be better allocated to long-term solutions that address the root causes of homelessness, such as creating more permanent affordable housing: as stated in Wong et al., for tiny home villages to succeed in their goals, affordable permanent housing must be available for individuals to transition into once aided by support services (LAHSA, 2023). As such, “the development of policies and programs that foster affordable homeownership and rental options for those with low incomes is a strategy for combating homelessness” (Evans, 2020, p. 361). While LA County aims to create 8,200 affordable homes in 2024, it is widely acknowledged that much more needs to be done (Ibid.).

These programs also lack community acceptance: it is often reported that homeowners, fearing that these communities will bring crime, disrupt traffic, increase littering, and decrease property value, provide significant negative verbal feedback during stakeholder consultations and conduct protests, making securing a site extremely difficult (Jackson et al 2020, pp. 9, 16). Researchers theorize that this is why 72% of tiny home communities in the United States are gated: vocal community members request to separate residents from those enrolled in the program (Evans, 2020, p. 367). As such, “[u]nderstanding perceptions of tiny house villages is important, because it is hypothesized that if such developments are perceived as… detriments to communities, they will face backlash and operational barriers” (Evans 2020, p. 368).

Jurisdictional clashes present a further concern. Attempting to provide diverse services requires collaboration between several organizations, including for-profit entities that provide the units, the city for construction and land use, non-profits that manage the sites, and LA County for mental health services. This may lead to dysfunction and long wait times to resolve issues, as multiple authorities must be contacted and coordinated.

Despite these concerns, the California state government has indicated that they will continue to build more tiny homes in the future, with a plan to construct 350 more homes in Sacramento, 200 in San Jose, 150 in San Diego, and 500 units in Los Angeles, prioritizing individuals that currently live in encampments (Office of Governor Gavin Newsom 2023).

2 Defined as maintaining consistent housing, either temporary or through transitioning to permanent housing.

3 In LA County, “affordable homes” are defined as those that are subsidized (Wisti, 2023).

Research Questions

Through this research, we aim to estimate the costs associated with operating and maintaining tiny home villages as an interim solution to homelessness. Furthermore, we also seek a greater understanding of funding breakdowns between local government entities and non-profit organizations and the reliance on charitable donations or non-governmental grants.

Whitsett West Tiny Home Village Pallet Shelters Photo: Ron Hall

Methodology and Data Analysis

Our research used a mixed methods approach, combining quantitative data analysis with qualitative interviews to develop a thorough understanding of the costs and services associated with tiny home villages in Los Angeles. We obtained the quantitative data from LAHSA through a public records request. This information spanned from the 2021 to 2023 operating years. The data from individual tiny home village budgets included federal and county fund allocations for constructing and operating tiny home villages. Moreover, the budgets included expenses such as rehabilitation, personnel, programming, and supportive services. Using descriptive statistics, we analyzed the data to identify financial trends in the early stages of tiny home villages in Los Angeles. The analysis then highlighted the most significant funding sources for tiny home communities, including how these compare across different villages.

For the qualitative data, we conducted ten one-on-one, semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders to gain insight into the implementation, operation, and maintenance of tiny home communities in Los Angeles. Each interview lasted approximately 30 minutes, with interview questions closely related to the intent of this research. To gain a comprehensive understanding of tiny home villages and homelessness overall, we connected with individuals in the government, the non-profit sector, the private sector, think tanks, and advocacy spaces.

At the local government level, individuals from the Los Angeles Mayor’s Office, two Council District offices, and the County of Los Angeles were interviewed. On the operational and maintenance end of tiny home communities, we spoke with individuals from Hope the Mission and Pallet Shelter. We were also interested in hearing from prominent organizations in the housing debate, such as the Manhattan Institute and California YIMBY.

The interviewees gave perspectives on the most integral parts needed to implement, fund, operate, and maintain these communities effectively. Interviews were transcribed and coded to qualitatively assess themes surrounding the construction, maintenance, and operation of tiny home communities, and to provide insight into the perceived benefits and challenges of this form of interim housing.

Quantitative Findings

The data we analyzed was collected through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request made to the Los Angeles Housing Service Authority. We analyzed the data in multiple ways to gain various insights into how the tiny home operators were spending money and where their funding was coming from.

The first way was by collecting the “Used” allocation budgets from the 2021-2023 operating years. The “Used Budget” is defined by how much of the awarded budget was used by tiny home villages. For example, Figure 2 displays 15 budget categories where tiny home administrators could allocate money for various costs. Many of the allocated budget categories were reported not to have used funding. None of the tiny home budgets given to us in our FOIA report had funding used for acquisition, administrative, indirect, or some other costs. Instead, the two central allocations for funding went to supportive and financial services or voucher costs for hotels and motels. Between these two allocations, nearly $40 million was used across each of the 11 tiny home villages analyzed. The following closest allocation was to non-personnel operating costs, which reached roughly $8.5 million. The remaining four categories — rental assistance, relocation, start-up operations, and start-up furniture fixtures and equipment — totaled around $8 million.

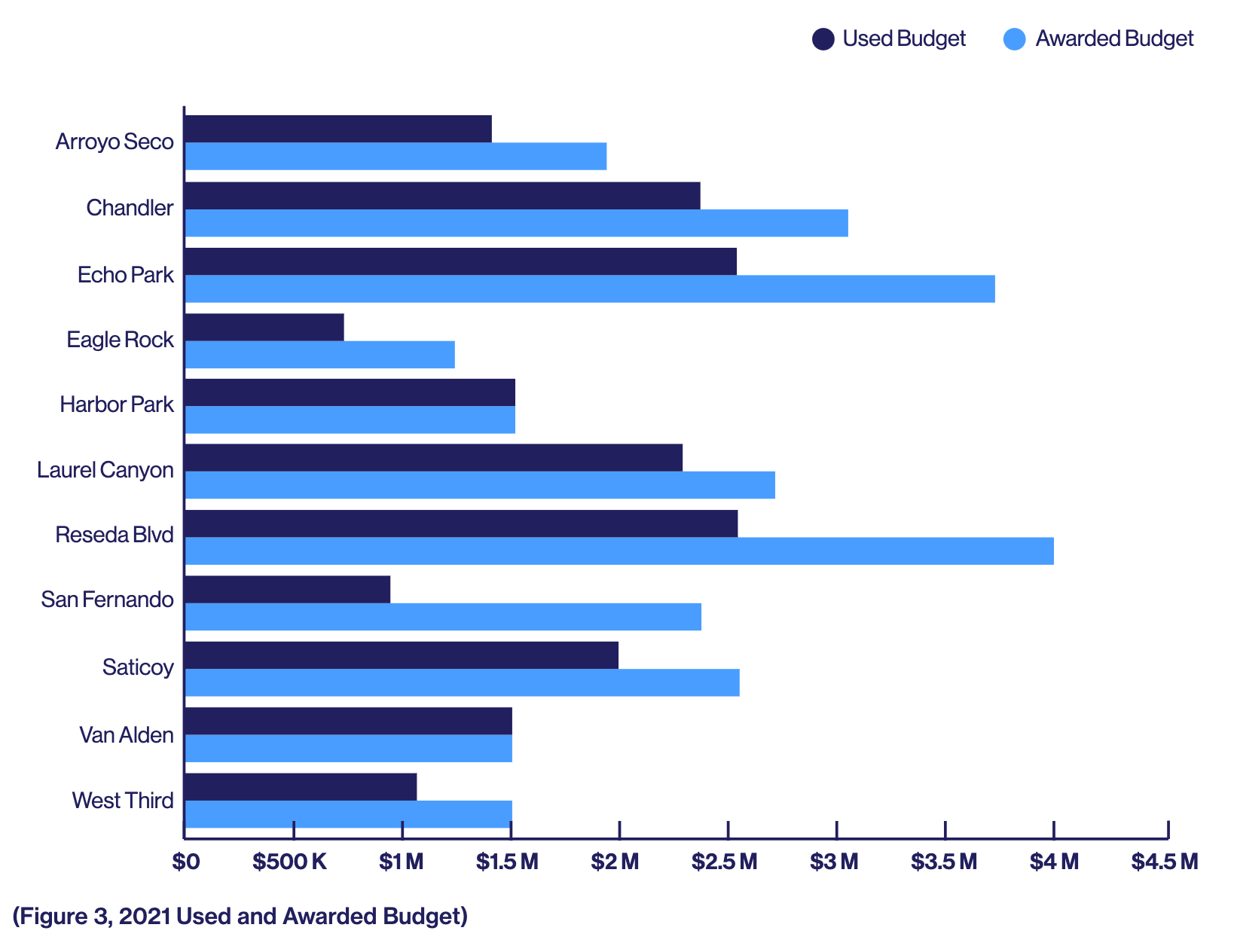

The following three graphs display the Awarded Budget and Used Budget for each of the 11 tiny home villages we analyzed. “Awarded Budget” displays how much funding was allocated to the tiny home that year, while the “Used Budget” shows how much of the awarded budget was used by the tiny home village. In 2021, only two of the 11 tiny home villages — Harbor Park and Van Alden — used the entire budget the county and federal government allocated to them. Indeed, according to Figure 3, a large majority of the tiny homes did not spend their entire awarded budget. The tiny home village on Reseda Boulevard and Echo Park declined to use $1 million of funding for the 2021 year they were awarded, which was primarily spread out between supportive services and vouchers for hotels and motels.

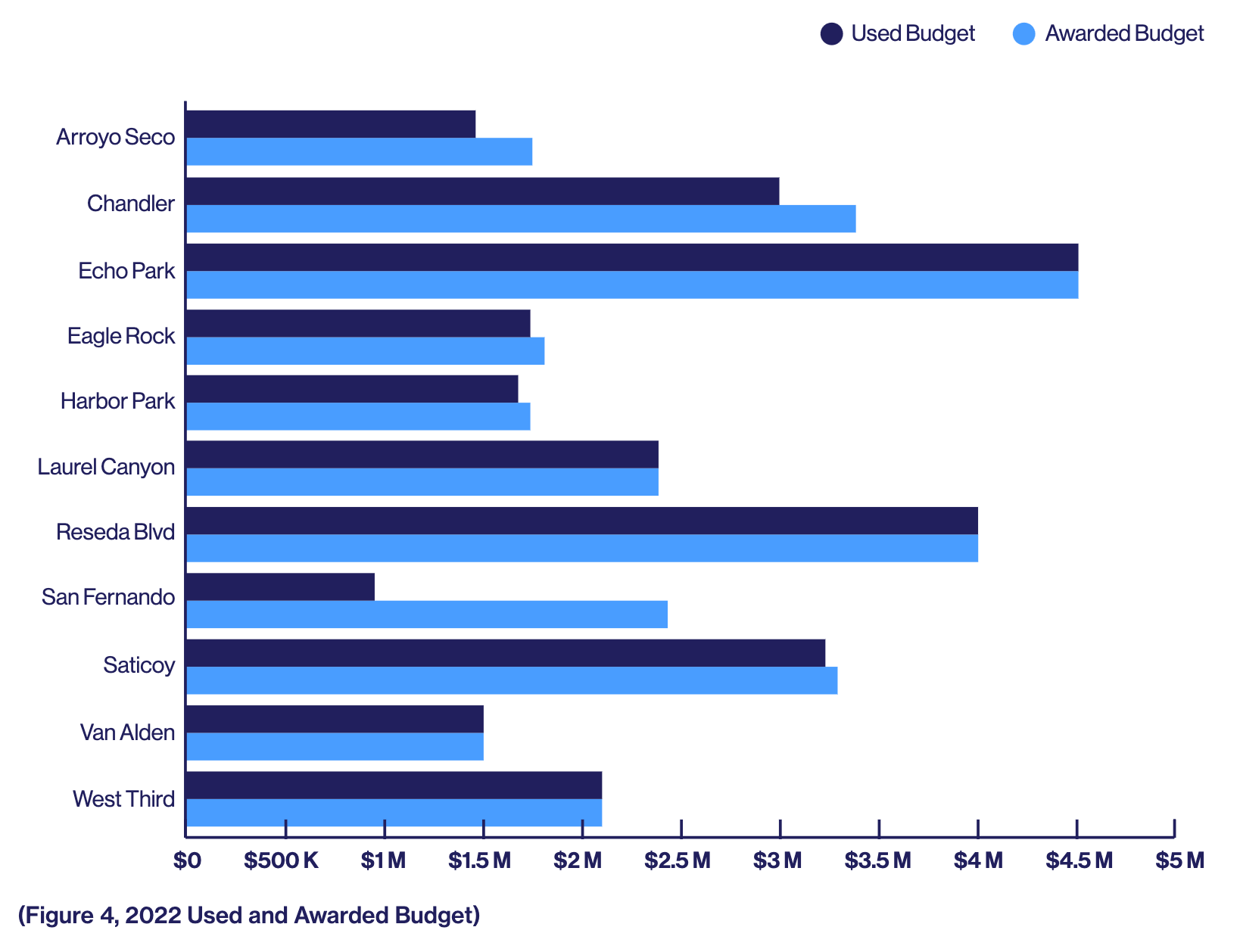

Figure 4 shows that in 2022 the operators changed their approach, as nearly every village used a majority, if not the full extent, of the budget awarded to them by government entities. This change could be in response to learning from the gaps present in 2021. The only tiny home village with a budget gap of over $1 million was the San Fernando tiny home village, primarily spread out hotel vouchers and operating costs. Notably, 2022 also saw a switch in the tiny home village that received the most awarded funding. Echo Park received around $4.5 million, primarily used for supportive services. In 2021, Reseda Boulevard received the most funding, slightly over $4 million, also from supportive services. We speculate that the demand for supportive services correlates with higher costs.

Figure 5 shows that the tiny home village’s spending habits in 2023, at first glance, mirrored those of 2021 rather than 2022, as every tiny home village operator has budget gaps when comparing their awarded and used budgets. However, the expiration date for a majority of the funding for the fiscal year is June 30th, 2024, meaning that when we received our data from LAHSA on February 7th, the tiny home villages still had well over four months to use the funding allocated to them.

No conclusions could be made during our research concerning whether the budget expenditures were “on track” this year for two reasons. First, the dates of when the spending amounts were last updated and sent to LAHSA by each tiny home village were not included in the data we received. Additionally, we know spending is not done in a linear fashion by tiny home village operators according to our qualitative research; therefore, it would be potentially inaccurate to provide a graph created linearly to forecast the budget gaps.

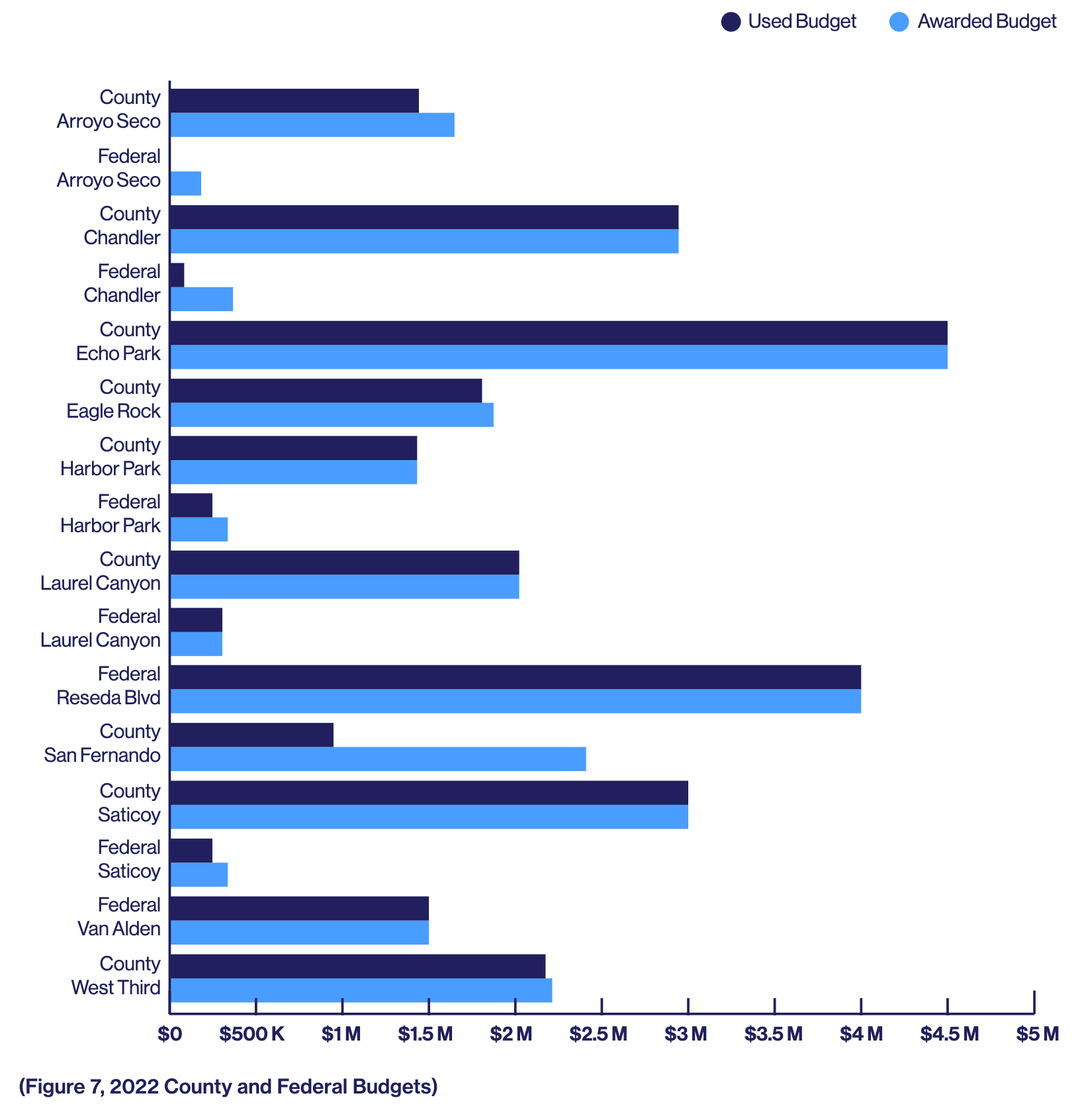

The final three figures in our paper demonstrate which government entity was funding the 11 tiny home villages. Figure 6 shows that in 2021, six tiny home villages received funding from county sources, and seven tiny home villages received funding from federal government sources. Budget gaps were present regardless of whether the allocated funding came from the county or federal government. Additionally, the funding split from either government source varied depending upon the tiny home village location.

Figure 7 had similar results, showing that in 2022, many tiny home villages received funding from the federal and county governments. Nevertheless, the budget gaps were much smaller across the board, consistent with Figure 3’s findings.

Figure 8 shows the most change. Aside from data not being received for the Laurel Canyon and West Third tiny home villages, no tiny home village in the 2023 operating year received funding from a federal government source except for the Harbor Park location. Nevertheless, the Harbor Park tiny home village did not use any of the money allocated to it by the federal government. It is unclear if the tiny home villages will receive further funding and investment from the federal government as they did in 2021 and 2022.

Qualitative Findings

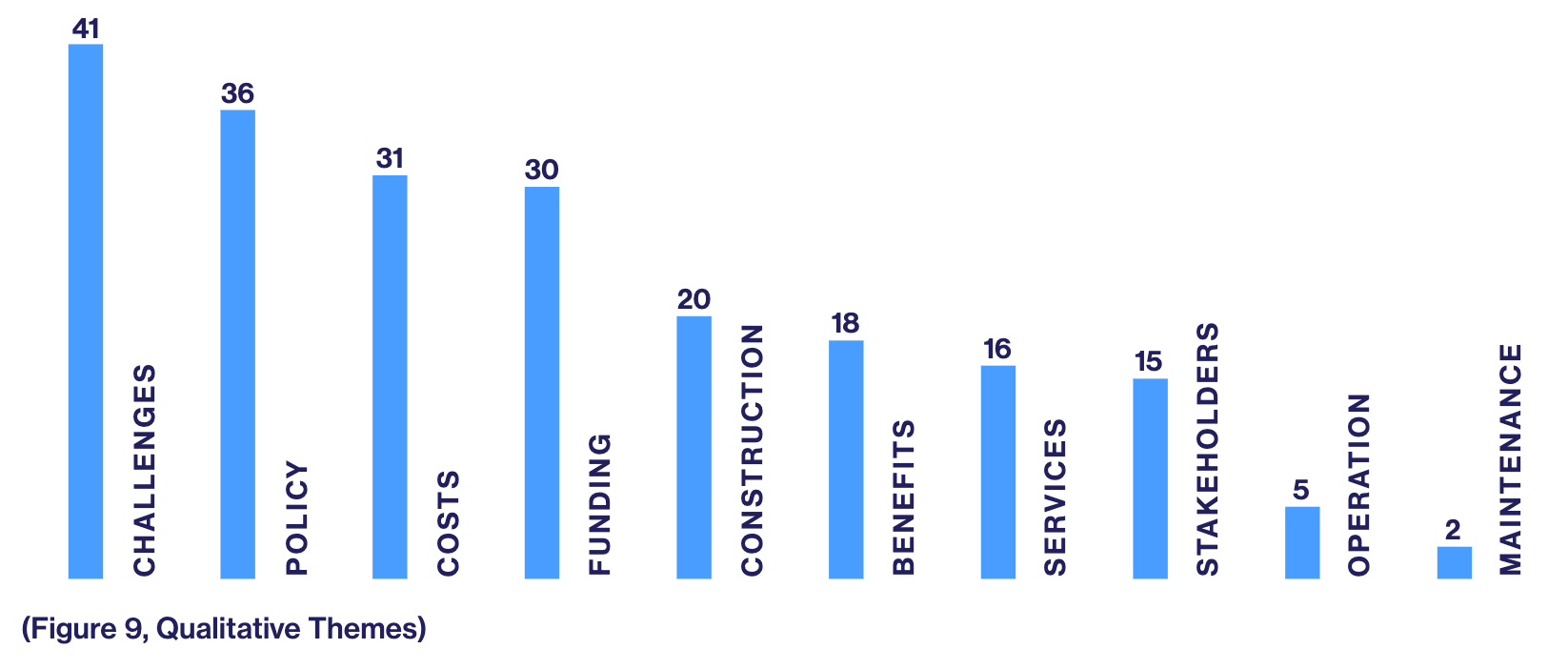

The objective of the semi-structured stakeholder interviews was to supplement the insights from the funding data received from LAHSA. During these dialogues, transcripts were recorded, and common themes present in the interviews were tallied through the use of the Atlas.ti software (Figure 9). Through this exercise, we were able to capture a better picture of funding allocations and perspective into potential benefits and inefficiencies.

Stakeholders repeatedly mentioned in these interviews included the County of Los Angeles and specific agencies within the county, such as the Department of Mental Health and the Department of Health Services. The county’s primary responsibility with tiny home communities is to provide mental health and medical services to tiny home community sites. The county also participates in decisions regarding land elements and unincorporated areas.

Throughout the interviews, the City of Los Angeles and Council Districts were also identified as key players in establishing this form of interim housing. Another essential stakeholder identified at the government level was the aforementioned Los Angeles Homelessness Services Authority. These organizations work together to supply tiny home providers with adequate land, resources, and funding to construct cabin communities. Other valuable stakeholders that were identified included non-profit organizations, which take on responsibilities related to the function and upkeep of communities for unhoused residents, and private-sector organizations like Pallet Shelter, which supply municipalities with tiny home units. It is also important to note that communities, research organizations, and advocacy groups are also named as essential stakeholders in the conversation around interim housing and public policies around homelessness.

One of the most common topics of discussion within these interviews was the challenges faced by the tiny home communities themselves, as well as those caused by relying on this method of housing over other alternatives. Within these challenges identified, the policies that increased costs and allocated funding were the primary concerns shared by all parties.

Funding And Costs From A Local Government Perspective

Local government representatives repeatedly emphasized the cost-effectiveness of tiny home communities in moving people off the streets when compared to alternative forms of housing. The first of these interviews was with an individual at a Council District office in Los Angeles proper. While discussing forms of interim housing in the district, this individual compared tiny homes and another prominent form of interim housing currently used in Los Angeles: hotel conversions. While utilizing existing hotels can be convenient because they are already built and thus readily available to meet demand, the cost per unit can be staggering. We were provided with an example of a typical hotel having a price tag of “$300 million to purchase that real estate, with 500 rooms– that would be about $600,000 per unit,” which was then compared to the average per-unit cost of a tiny home for that district, which was only $65,000. While tiny home communities are not necessarily an inexpensive form of interim housing, according to the interviewee, they are “a more cost-effective method of quickly providing housing…than acquiring existing real estate… or the time-consuming process of entitling and building new facilities.”

Another individual at a Council District office in the San Fernando Valley further praised the use of tiny homes over hotels. In addition to the significant property cost, “hotels often involve enormous retrofits in order to get them up to par,” lacking critical infrastructure to provide necessities like food. This further inflates the investment required and can be a much more complicated process than building new infrastructure in a tiny home community. Utilizing the tiny home model further stretches the limited funding available to Council Districts by allowing them to grant the non-governmental organizations that run them – like Hope the Mission – only a majority of the total funding required to operate, expecting these groups to fundraise the remaining amount themselves.

This same individual described large pots of money that are available through federal and state sources but are awarded to specific projects proposed by Council Districts, stating that “some of the most important resources that we have as a city is being able to apply for those things.” Interestingly, they also identified a core misunderstanding held by the public regarding funding: many of these available sources are designated such that they can only be awarded to transitional forms of housing, so they do not in fact impact the uptake of permanent supportive housing or other proposed mitigation methods.

Our discussion with a representative of the Los Angeles Mayor’s Office further reiterated the agency of Council Districts. The individual we spoke with discussed Mayor Bass’s recent Inside Safe initiative and the role of city government in driving funding for tiny home communities, stating that “…[a]s far as the funding is concerned, that is really driven by the Council Districts,” as they must take the initiative and apply to available grants through LAHSA. They further stated that “[t]here is some city funding that goes into [interim housing], but it’s not nearly as much as we would definitely like for it to be.”

Funding And Costs From Non-Governmental Organizations

This sentiment was echoed by many of the Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) interviewed. Tiny home operators repeatedly emphasized that there was simply not enough funding allocated to effectively manage the homelessness crisis currently taking place or even properly serve those currently housed in their existing tiny homes. As previously mentioned, LAHSA does not provide adequate funding to cover operating costs. From the interviews conducted, we gathered that although it varies between sites, it usually costs between $80 and $90 a day per person to provide security, three meals, case management, client services, and staff. Organizations like Hope the Mission receive approximately $60 per person on average, and privately fundraise the remaining $20 to $30. This not only takes immense resources but also prevents the expansion and improvement of existing services. Importantly, this $80 to $90 “bed rate” does not cover any tertiary services, like supplementary mental health or recovery programs. These services are viewed as essential by Hope the Mission staff but are highly dependent upon the success of their fundraising efforts, which can be highly speculative.

This uncertainty is worsened by the established process for funding allocation. NGOs are paid in arrears: Hope the Mission pays all costs upfront and is reimbursed sometime later. According to our interviewees, this has resulted in an organizational deficit of $17 to $18 million, which limits their ability to respond to crises or an influx of unhoused individuals quickly. Repairs further compound this: because of this allocation process, maintenance costs must be predicted and built into the annual budget, further obscuring the actual value of their remaining funds.

Housing-first advocacy groups consulted for this study shed further light on the difficulties of relying on these government funds. Historically, many programs designed to reduce homelessness operate largely on one-time grants and funding allocations, making long-term planning challenging. This prevents the uptake of subsidized permanent housing and hinders strategic budgeting for tiny home communities. A contributing factor described within these interviews was California’s reliance on income tax rather than property taxes: the government is dissuaded from guaranteeing long-term funds because total tax revenue may fluctuate yearly.

Interestingly, these same advocates placed a considerable emphasis on the negative con- sequences of major investment in this method of interim housing, primarily how the significant attention drawn by this approach has reduced the allocation of funding to alternative solutions, particularly the aforementioned subsidized housing and construction of more affordable housing in general: “I do not think that policymakers have fully appreciated the connection between homelessness policy and housing policy, and the fact that bad housing policy is the cause of the homelessness crisis.”

Whitsett West Tiny Home Village bathroom and hygiene trailer Photo: Ron Hall

Jurisdictional Concerns And The Division Of Responsibility

Aside from funding and costs, the policies and perceived dynamics between government, NGOs, and other stakeholders were a recurring topic of conversation. As previously mentioned, a large number of organizations are involved in different aspects of tiny home community development and upkeep. Several of these stakeholders reported inefficiencies caused by other organizations. Pallet Shelter found that, because there is currently no International Building Code for tiny homes, cities tend to over-engineer or over-design these communities, leading to a total cost of $100,000 per unit for Los Angeles’ first community. With experience, these costs have fallen dramatically – to around $30,000 – primarily due to the realization that site selection should prioritize locations with existing connections to electricity, water, and sewage systems, but the shelters themselves cost only $11,000, and Pallet believes there are still improvements to be made to expedite the process and reduce costs.

One way in which costs have been reduced is by taking advantage of land already owned by the city that can be used as a community site, instead of purchasing new land. However, finding unused property that meets the aforementioned requirements for a tiny home community— existing electricity, water, and sewage connections —takes time, and has created a bottleneck for the development of new communities.

This bottleneck is further compounded by the influence of groups of homeowners and residents who are diametrically opposed to these kinds of programs, commonly known as “Not in my Backyard’ers” (NIMBY)’s. Even if a suitable location owned by the city is found, local reception can dissuade districts from moving forward with the proposal. Interviewees often referenced public perception of these communities to equate to a “slum” being constructed in their neighborhood, and recalls of local representatives are often threatened. Those within government emphasized the importance of conducting community outreach and stakeholder consultations so that local voices can be heard and educated. If this is properly carried out, public sentiment has been shown to shift more positively. Similarly, NGOs described how bad press has been the most effective catalyst for government action. This is what first pushed the reduction in development costs, and encourages the city to maintain sites.

However, in practice, this is not enough of an incentive. Providers reported long delays for repair requests to be completed. Because so many organizations control different facets of the community, obligations were often ignored for long periods of time, while others lacked the authority to solve the issues themselves. In a similar vein, it was widely reported that LAHSA would rarely share information with any other organization, which complicated efforts to provide known individuals with relevant resources and treatment, and further posed a potential security risk.

A further disconnect reported between LAHSA and Hope the Mission regarded the allocation of Time-Limited Subsidy (TLS) vouchers. The primary purpose of these vouchers is to help transition residents out of tiny home villages meant for interim housing and into permanent housing solutions. The vouchers play a role in subsidizing permanent housing access once a resident is matched with a suitable home and ready to leave the tiny home community. However, most of these are only valid for 90 days: finding suitable housing is a complicated task and often takes far longer than this, so these limits only serve to slow the transition rate from interim to permanent housing. This was common knowledge amongst Hope the Mission employees, but LAHSA continues to set this arbitrary limit.

Widely-Recognized Benefits

Despite the aforementioned issues, every individual interviewed acknowledged the many benefits of providing this method of interim housing. Discussions often mentioned the “3 P’s”: Pets, Partners, and Privacy. Tiny home communities offer a range of pet services, like pet food, a dog park and consistent cleaning, that enable unhoused individuals to enjoy the mental health benefits of pet ownership without sacrificing their limited resources. An enclosed space with a locking door also allows clients to enjoy privacy and security from others if they so wish, and because – unlike congregate shelters – these communities are not separated by gender, individuals can foster relationships and see their partners far more easily. These three regular parts of life are essential in providing a sense of normalcy, dignity, and stability to unhoused individuals, and clients are only free to experience these regularities in tiny homes as they are usually banned or unattainable in congregate shelters. The speed at which more units could be deployed (absent the barriers highlighted above) also impressed most.

Whitsett West Tiny Home Village laundry facilities Photo: Ron Hall

Policy Recommendations and Discussion

Through this research, it is apparent that every tiny home village is different, and there is no adequate “one-size-fits-all” approach to homelessness. However, with thousands currently living on the streets of Los Angeles, something must be done. After analyzing the data provided by LAHSA and interviewing various stakeholders, we have formulated recommendations to potentially address funding concerns and policy barriers that may be preventing tiny homes from reaching their full potential and goal of helping as many people transition from living on the streets to living in safer, permanent housing.

Increase The Availability Of Permanent Housing

A challenge that was reiterated throughout the interviews was that the availability of affordable permanent housing is insufficient to meet current needs. This has resulted in tiny home villages straying from their initial mission of providing interim housing and becoming pseudo-supportive permanent housing as clients wait in limbo. According to one stakeholder, “We’ve kind of gotten caught in America in this ‘either-or’ narrative, and it’s really not an ‘either-or’ narrative. It’s a ‘both-and.’” It is necessary to invest in permanent housing, and we also have to invest in interim solutions.” Increasing the duration of subsidization would reduce the likelihood of individuals falling back into homelessness after this assistance runs out. This would also require the extension or removal of the time-limited aspect of these vouchers, as currently this is an unrealistic expectation and only serves to add another barrier to the transition to permanent housing. Limited housing vouchers are not solely an issue that falls on municipalities, but also on the federal government. There must be flexibility in housing resources for individuals who can exit the tiny home program to open beds for unhoused individuals to transition in.

It is also necessary for California lawmakers and leaders to prevent people from falling into homelessness. California is experiencing a housing crisis, and this severe lack of supply is often what drives individuals to live on the streets in the first place. This shortage is the direct result of well-intentioned policies that have made it harder to build: there is a clear preference for single-family homes with a minimum acreage. Restrictive zoning often prevents the construction of affordable housing. While there is nothing inherently problematic with the single-family housing model, it has drastically increased the barrier to entry into the housing market by increasing the average cost of renting a home and reducing potential options. California leaders at the state and local levels should reevaluate existing policies that make building more affordable housing difficult, and streamline the process for less expensive, smaller dwellings like apartment buildings to be built.

Increase Funding And Access To Essential Services

Providing a person experiencing homelessness with a home may not be enough. While housing first is a step in the right direction, the fact of the matter is that homelessness is a multifaceted policy issue. Los Angeles is experiencing a housing crisis but also crises related to mental health and substance abuse. To ensure someone’s success in permanent housing, the government must continue to invest in mental health and substance abuse services through the County of Los Angeles and LAHSA. This could include additional state and federal funding, and advocacy around state propositions that would funnel money into this specific form of care. It should be the state’s priority to provide targeted wraparound services to unhoused individuals experiencing mental health or substance-related crises. These financial investments will ensure that those who move to permanent supportive housing are receiving the resources they need to lead healthier and more abundant lives. Focusing on an individual’s overall well-being can also help formerly unhoused people lead healthier and more abundant lives, while addressing concerns from community members. Although a large portion of existing funding is already allocated to providing this, our interviews with providers detailed how this significant figure is still insufficient to provide a real solution, forcing them to fundraise for supplementary services themselves.

Whitsett West Tiny Home Village supply storage container Photo: Ron Hall

Mandate Increased Communication, Transparency, And Cooperation Between Organizations

Another challenge that can be addressed is increasing transparency and communication between local government agencies. While the local government stakeholders who were interviewed considered their relationships with other agencies generally positive, a challenge that was emphasized was accessibility to data from agencies like LAHSA. Homelessness is a policy issue that can only be solved through persistent collaboration; otherwise, resources will inevitably be wasted. All stakeholders are invested in improving the lives of their clients, so all should have access to vital information that can assist in this. As LAHSA is a joint-powers authority, it currently lacks sufficient oversight and incentive to effectively cooperate with other agencies. Requiring this would greatly improve the experience for all organizations involved.

Prioritize Long-Term, Consistent, But Flexible Funding

California’s current preference for short-term, singular budget infusions prevents any form of realistic long-term planning from taking place. When it comes to housing, this is simply not effective. Construction of permanent housing alone can take years, and there is no guarantee that funding for subsidization will be available by the time this is completed. For tiny home communities, they can never be sure how much funding they will be receiving from year to year, preventing them from planning expansions of existing services or new communities.

This system also requires budgets to be inflexible: as previously mentioned, community repairs must be predicted annually and built into each community’s budget. This leads to inefficient spending and budgeting because communities are wary of spending their funds in case they run out of money to cover unexpected issues. This is likely why our quantitative analysis determined that most sites rarely used the entirety of their budgets: it would be reckless to maximize one’s funds through a long-term plan when this necessarily means that they will not be able to repair any breakages until the next fiscal year. A preferable budgetary system would guarantee a consistent annual amount to each site for several years, with a separate fund established to cover any repairs. This would encourage communities to use the entirety of their budgets to provide the best services they possibly can with the funds allocated, without fear of unexpected costs appearing throughout the year.

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to shed light on the current budgetary breakdown of tiny home communities in LA County, to determine if they are properly serving their purpose in reducing homelessness. Through both quantitative and quantitative analysis, we found that although they are effective at moving people off the street and providing desperately-needed services, the lack of affordable permanent housing options severely hinders their effectiveness as temporary shelter, as many have no option but to stay indefinitely. This forces these organizations to increasingly become permanent housing providers, which is neither their mission nor realistic given their budget. As such, we recommend increasing the availability of permanent housing through zoning reform, increasing funding for essential mental health services, mandating increased communication and information-sharing between shareholders, and implementing a long-term and flexible approach to budget allocation. Adopting these policy recommendations will reduce inefficiency in this critical service and better accomplish the aims of these tiny home communities.

Whitsett West Tiny Home Village close up of a shelter Photo: Ron Hall

Reference List

Bozorg, L., & Miller, A. (2014). Tiny Homes in the American City. Journal of Pedagogy, Pluralism, and Practice, 6(1), 125.

https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/jppp/vol6/iss1/9.

Calhoun, K. H., Wilson, J. H., Chassman, S., & Sasser, G. (2022). Promoting Safety and Connection During COVID-19: Tiny Homes as an Innovative Response to Homelessness in the USA. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-022-00217-0.

California Official Voter Information Guide. “Proposition 1 Arguments and Rebuttals | Official Voter Information Guide | California Secretary of State.” Voterguide.sos.ca.gov, 2024,

voterguide.sos.ca.gov/propositions/1/arguments-rebuttals.htm.

County of Los Angeles Homeless Initiative (2023). Homeless Initiative Strategies. LA County,

https://homeless.lacounty.gov/strategies/.

County of Santa Clara. (2023, May 30). County of Santa Clara and City of San José Release Preliminary Results of 2023 Point-In-Time Homeless Census. County of Santa Clara, County News Center, Office of Communications and Public Affairs.

https:/news.santaclaracounty.gov/news-release/county-santa-clara-and-city-san-jose-release-preliminary-results-2023-point-time.

Congress. “H.R.748 – 116th Congress (2019-2020): CARES Act.” Www.congress.gov, 27 Mar. 2020,

www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748.

Davalos, M., & Kimberlin, S. (2023, March). Who is Experiencing Homelessness in California? California Budget and Policy Center.

https://calbudgetcenter.org/resources/who-is-experiencing-homelessness-in-california/.

de Sousa, T., Andrichik, A., Prestera, E., Rush, K., Tano, C., & Wheeler, M. (2023). The 2023 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress.

https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2023-AHAR-Part-1.pdf.

Evans, K. (2020). Tackling Homelessness with Tiny Houses: An Inventory of Tiny House Villages in the United States. The Professional Geographer, 1–11.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2020.1744170.

Foundation, T. A.-M. (n.d.). New Report Estimates Costs of Los Angeles Tiny Home Villages Intended to Combat Homelessness. Www.prweb.com. Retrieved December 9, 2023, from

https://www.prweb.com/releases/New_Report_Estimates_Costs_of_Los_Angeles_Tiny_Home_Villages_Intended_to_Combat_Homelessness/prweb18532499

htm#:~:text=The%20A%2DMark%20Foundation%20calculated.

FY 2022-23 Approved Budget – Homeless Initiative. (n.d.). Homeless.lacounty.gov.

https://homeless.lacounty.gov/2022-2023-budget/.

Tiny Houses for the Homeless? WBTV Asks LA Nonprofit if Unique Concept Could Work in Charlotte. (2021, February 23). Alex Giles.

https://www.wbtv.com/2021/02/24/tiny-houses-homeless-wbtv-speaks-with-la-nonprofit-about-whether-unique-concept-could-work-charlotte/.

Governor Newsom Announces $1 Billion in Homelessness Funding, Launches State’s Largest Mobilization of Small Homes. (2023, March 17). California Governor.

https://www.gov.ca.gov/2023/03/16/governor-newsom-announces-1-billion-in-homelessness-funding-launches-states-largest-mobilization-of-small-homes/.

Grover, J. (2023, December 1). LA Mayor’s “Inside Safe” Effort: $67 Million Spent, Only 255 Homeless People Permanently Housed. NBC Los Angeles.

https://www.nbclosangeles.com/investigations/la-mayor-inside-safe-homeless-housing-program/3281201/#:~:text=Shortly%20after%20taking%20office%20in.

Jackson, A., Callea, B., Stampar, N., Sanders, A., De Los Rios, A., & Pierce, J. (2020). Exploring Tiny Homes as an Affordable Housing Strategy to Ameliorate Homelessness: A Case Study of the Dwellings in Tallahassee, FL. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 661.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020661.

Krista, E. (2018). Integrating tiny and small homes into the urban landscape: History, land use barriers and potential solutions. Journal of Geography and Regional Planning, 11(3), 34–45.

https://doi.org/10.5897/jgrp2017.0679.

Local Housing Solutions. “Los Angeles Proposition HHH.” Local Housing Solutions, 2024,

localhousingsolutions.org/housing-policy-case-studies/los-angeles-proposition-hhh/.

Lyster, L. (2023, November 15). Emergency calls piling up at L.A.’s tiny home villages. Yahoo News.

https://news.yahoo.com/emergency-calls-pile-l-tiny-174631091.html.

Pallet Shelter. “Los Angeles: 1,200+ New Beds for Unhoused Neighbors.” Pallet Shelter, 2024.

palletshelter.com/case-studies/los-angeles-california/

Pallet Shelter. “Why Pallet.” Pallet Shelter, 2024,

palletshelter.com/why-pallet/.

Schlepp, T. (2022, July 20). First unhoused residents move into Montebello tiny home village. KTLA.

https://ktla.com/news/local-news/first-unhoused-residents-move-into-montebello-tiny-home-village/.

Thornton, C. (2023, October 16). With homelessness high, California tries an unorthodox solution: Tiny house villages. USA TODAY.

https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2023/10/16/tiny-homes-shelter-homeless-california/71153631007/.

Unity Parenting and Counseling. (2021, October 18). How Homelessness Affects the Community. Unity Parenting and Counseling.

https://unityparenting.org/homelessness-affects-the-community/.

US Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2022). The 2022 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress, pp. 16-30. HUD Office for Community Planning and Development.

https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2022-AHAR-Part-1.pdf.

Wisti, Erin. (2023, December 19). What Does ‘Affordable Housing’ Really Mean in Los Angeles? L.A. Taco.

https://lataco.com/affordable-housing-really-mean.

Wong, A., Chen, J., Dicipulo, R., Weiss, D., Sleet, D. A., & Francescutti, L. H. (2020). Combatting Homelessness in Canada: Applying Lessons Learned from Six Tiny Villages to the Edmonton Bridge Healing Program. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6279.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176279.

Yee, C. (2023, June 29). LAHSA Releases Results Of 2023 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count. Www.lahsa.org.

https://www.lahsa.org/news?article=927-lahsa-releases-results-of-2023-greater-los-angeles-homeless-count.

Zahniser, D. (2023, July 29). 1 out of 6 people have left the housing provided by L.A. homeless program, agency says. NewsBreak.

https://www.newsbreak.com/news/3105348825648-1-out-of-6-people-have-left-the-housing-provided-by-l-a-homeless-program-agency-says

Appendix:

Appendix Figure 1: Tiny Home Communities In LA County

| Village Name | Tiny Homes Available | Beds Available | Address |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chandler | 40 | 75 | 11471 Chandler Blvd, North Hollywood, CA 91601 |

| Alexandria Park (Laurel Canyon) |

103 | 200 | 6099 Laurel Canyon Road, North Hollywood, CA 91606 |

| Topham/Tarzana (Reseda Blvd) | 75 | 150 | 18616 Topham St., Reseda, CA 91335 |

| Van Alden | 52 | 101 | 19035 W Vanowen St, Reseda, CA 91335 |

| Whitsett West (Saticoy) | 77 | 150 | 12550 Saticoy Street |

| Arroyo Seco | 117 | 224 | 401 Arroyo Seco Pkwy, Los Angeles, CA 90042 |

| Echo Park | 38 | 76 | 1455 N Alvarado St, Los Angeles, CA 90026 |

| Eagle Rock | 48 | 93 | 7570 North Figueroa Street |

| San Fernando | 39 | 78 | 9710 San Fernando Road, Sun Valley, CA 91352 |

| Westlake (West Third) | 55 | 107 | 2301 West 3rd Street, Los Angeles, CA |

| Harbor Park | 75 | 150 | 1221 Figueroa Place, Wilmington, CA 90744 |

Appendix Figure 2: Quantitative Code Book for Line of Best Fit

| Village Name | Tiny Homes Available |

|---|---|

| Van Alden | VA |

| Reseda Blvd | RB |

| Chandler | CH |

| Laurel Canyon | LC |

| Harbor Park | HP |

| Echo Park | EP |

| Arroyo Seco | AS |

| Saticoy | Saticoy |

| West Third | WT |

| Eagle Rock | ER |

| San Fernando | SF |

Interview Questions

Participant Background (Description of the Study)

- Can you introduce yourself, your role/position title, and your responsibilities at (insert organization here)?

- Question more specific to their background in housing and what led them to the tiny homes initiatives*

- Question more specific to their background in housing and what led them to the tiny homes initiatives*

Tiny Home Initiative

- What do you see as the main benefits of using tiny homes to provide shelter for people experiencing homelessness?

- What are some of the drawbacks of using tiny homes to provide shelter?

- How does your tiny home village compare to other tiny home villages in Los Angeles?

- What supportive services (case management, healthcare, job assistance, etc.) are provided on-site in tiny home communities? Are there any services that are not provided that you believe should be provided?

- What public or philanthropic funding sources are available to pay for these services?

- Do you find that these sources are sufficient to cover the costs of operating the program?

- What criteria or process do you use in determining who is eligible to live in a tiny home village serving the homeless?

- Do you believe the tiny-home operators’ priorities are well understood or represented in statewide discussions about homelessness policy?

- How would you describe the relationship between local elected leaders (mayor and city council) and the homelessness issue in LA?

- What are your thoughts on tiny homes in general and do you think they can be a successful solution to LA’s homelessness crisis in particular?

- Please outline your reasons for the previous statement.

Implementation Process

- Please describe your experience with the implementation process for tiny home villages in Los Angeles.

- What is a realistic range for the per unit cost of constructing a tiny home community or village in Los Angeles? Does this differ substantially from the cost of other housing alternatives?

- How much do you estimate the monthly utility and maintenance fees would be for a tiny home unit in LA? How does this compare to the operating costs of a shelter bed or supportive housing apartment?

- How many people could be served by establishing one or more tiny home villages in LA? How was this number determined?

- How many individuals, on average, transition into permanent housing annually?

- On average, what percentage of individuals drop out of the program annually? What are the primary reasons given for dropping out of the program?

- What are the main concerns with the spending around tiny homes in LA?

- Would you recommend the city directly fund and operate tiny home villages for the homeless or rely on partnerships with non-profit service providers? What are the tradeoffs of each approach?

- Do you foresee any challenges with any of the following: zoning, land use permits, or community support for siting tiny home projects in residential neighborhoods?

- If so, how would you recommend overcoming these challenges:(zoning, land use permits, or community support for siting tiny home projects in residential neighborhoods)?

Challenges and Best Practices

- What recommendations do you have regarding rules, policies, or management strategies for creating safe and well-functioning tiny home villages for formerly homeless individuals?

- What is preventing the full potential of tiny home villages?

- What is the one thing you believe LA does best in supporting tiny home operators?

- What would you describe as the single biggest problem facing LA’s tiny home communities?

- How would you describe the organizational dynamics of the city and non-governmental efforts around homelessness and tiny homes?

- What group do you believe is most heard (or disproportionately heard) in discussions about homelessness and tiny homes in LA?

- Are there any stakeholders or groups that are not currently participating in the homelessness and tiny-home discussion in LA but should be a part of it?

- For others interested in setting up your programs, how would you do it?

- If you had to do this over again, how would you implement this program?

- If you could implement one change to improve the operations of tiny homes in LA, what would it be?

- Who else should we reach out to/what should we research further?

- Is there anything that we did not talk about in today’s interview that you believe would be important for us to know?

Qualitative Code Book for Interviews

| Section | Description | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Construction of Tiny Homes | Mention of the construction and implementation of tiny home villages | CON_TH |

| Funding | Mention of funding (sufficient or insufficient) associated with the implementation, operation, and/or maintenance of tiny home villages |

FUND |

| Services | Mention of housing, substance abuse, and mental health services offered in tiny home village communities | SERV |

| Challenges | Mention of challenges associated with the implementation, operation, and/or maintenance of tiny home villages | CHALL |

| Benefits | Mention of benefits associated with the implementation, operation, and/or maintenance of tiny home villages | BENE |

| Maintenance | Mention of maintenance of tiny home villages | MAIN |

| Operation | Mention of operation of tiny home villages | OPER |

| Stakeholders | Mention of important stakeholders/groups | STA_HOL |

| Costs | Mention of specific budget items or numbers | COST |

| Policy | Mention of planning policy, public policies, or navigating the policy landscape | POL |